Begun by Clifford Barnes over 100 years ago, The Chicago Sunday Evening Club (CSEC) held its first Sunday evening service in Orchestra Hall on February 16, 1908. (As a side note, Barnes was the first resident male worker at Hull House in Chicago). With a non-denominational orientation, the services were intended for business persons traveling through Chicago by train as many trains were idled on Sunday leaving many individuals in the city until Monday. Barnes and other leaders worked hard to develop a strong reputation for interesting speakers and well performed music, so much so that it began to attract Chicago residents as much or more than business people passing through. It was not unusual for the Club to average 2000-2500 people at Orchestra Hall every Sunday night. There was a different speaker every week, but some speakers were invited to return year after year.

In those early years, some of the best-known names in American religion and public life were speakers on the programs, including social worker and reformer Jane Addams, William Jennings Bryan, Rabbi Stephen Wise, Booker T. Washington, and Reinhold Niebuhr.

In those early years, some of the best-known names in American religion and public life were speakers on the programs, including social worker and reformer Jane Addams, William Jennings Bryan, Rabbi Stephen Wise, Booker T. Washington, and Reinhold Niebuhr.

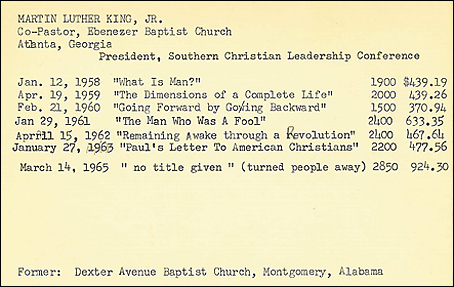

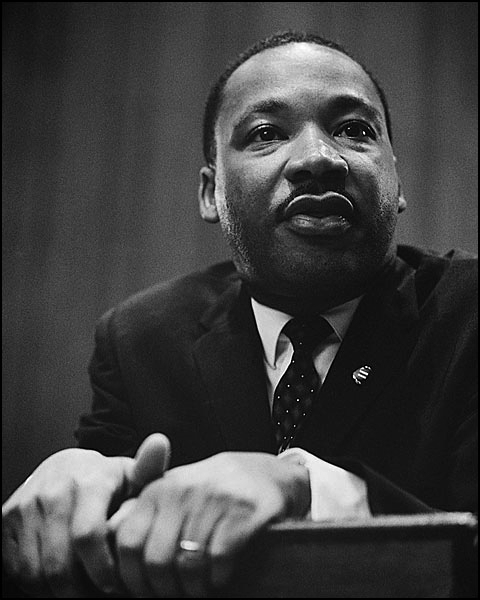

By the middle 1960’s one of the repeat speakers was Martin Luther King, Jr. King’s first visit to the CSEC was in January 1958 as he preached a sermon titled “What is Man?” This visit was followed by April 1959 (“The Dimensions of a Complete Life”), February 1960 (“Going Forward by Going Backward”), January 1961 (“The Man Who Was A Fool”), April 1962 (“Remaining Awake through a Revolution”) and January 1963 (“Paul’s Letter to the American Christians”).

In his 1962 speech, Dr. King said too many Americans were like Rip Van Winkle, snoozing through the changes happening around them. During two of these visits to Chicago the young Hillary Rodham made her way downtown to hear King speak. Though there has been some very minor controversy over her recollections of those visits, Rodham Clinton has spoken of the deep influence King had upon her social and political thinking.

On March 14, 1965, in the recent wake of the Selma marches, several Wheaton College students made their way to Chicago to hear King preach at the Chicago Sunday Evening Club in Orchestra Hall. Speaking from the Book of the Revelation (21:26ff), King spoke of balanced human fulfillment, comparing the symmetry of the Holy City (equal in length, breadth and height) to well-developed individual. This complete individual has a true sense of one’s relation and duty to one’s neighbor and to God. Students commented later that they believed the sermon would have been “perfectly appropriate in any evening service among the churches in Wheaton.” However, the student’s perspective was not that of the FBI. Taylor Branch, in At Canaan’s edge: America in the King years, 1965-68, notes that at this time FBI agents were monitoring King’s travel and activities, including the press conference held at O’Hare airport upon his arrival in Chicago and his televised CSEC sermon. Updates were reported to Washington throughout the visit. His sermon was characterized as “primarily religious sermon, no reference Bureau or government, and only passing reference racial matters. Military and Secret Service advised” (p. 801). King’s only reference to the events of Selma during his sermon was noting that the key to racial harmony was not through external coercion but internal reawakening to the necessity of the New Testament ethic of love.

Even though the Club continued having an impressive list of speakers, including names like Paul Tillich, Ralph Sockman, and Elton Trueblood, the Orchestra Hall programs after 1965 saw average attendance in the range of 200-300 people, rather than the 2000-2500 that King saw. This put financial strains on the Club’s resources because a long-term lease had been signed. In 1968 when the lease expired the Club ceased its meetings there. The CSEC took advantage of new color television technology. Retaining the original format of its program the Chicago Sunday Evening Club became a televised service on Chicago’s WTTW, where it remains today.

Wheaton College Archives & Special Collections houses one of two archival collections of Chicago Sunday Evening Club records and measures over 9 linear feet. This complements a collection housed at the Chicago History Museum (1908-1975, primarily speaker files from 1940-1965). The Wheaton collection contains corporate records, publications, speaker’s addresses, broadcasting information, correspondence, and a small amount of secondary information.