In recent years much has been happening in the world of unions, collective rights and strikes. April 1st marks the anniversary of what has been called the longest strike in history. What makes the story of this strike amazing, along with its length, was who the strikers were. On April 1, 1914 the dismissal of the teachers of the local school in Burston, Norfolk, England took effect. Kitty and Tom Higdon were relieved of their duties. In response to this 66 of the school’s 72 children went on strike and marched about the village demanding the return of their teachers. Officially, the strike never ended.

In recent years much has been happening in the world of unions, collective rights and strikes. April 1st marks the anniversary of what has been called the longest strike in history. What makes the story of this strike amazing, along with its length, was who the strikers were. On April 1, 1914 the dismissal of the teachers of the local school in Burston, Norfolk, England took effect. Kitty and Tom Higdon were relieved of their duties. In response to this 66 of the school’s 72 children went on strike and marched about the village demanding the return of their teachers. Officially, the strike never ended.

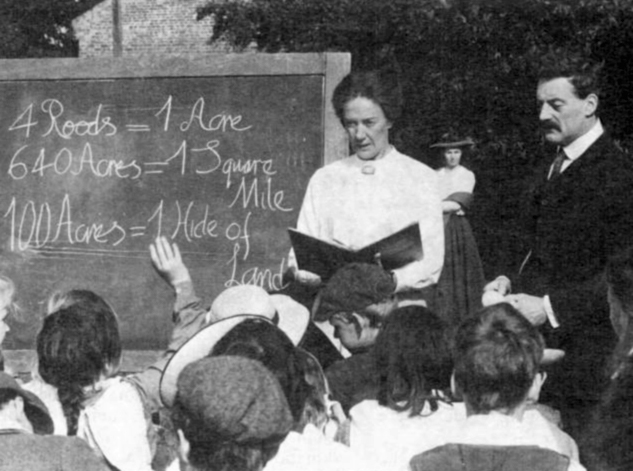

In 1902 Parliament passed the Education Bill that stated that working-class children were entitled to an education. In places like Burston that education prepared students for little more than work in the factories, fields or domestic service. Christian educators like Tom and Kitty Higdon believed that that all children should have a better education than what many districts offered. They saw that education was an opportunity for a better life. In 1902 the Higdons began teaching near Aylsham, thirty-some miles from Burston. It was here, in this highly agricultural area, that they organized an agricultural workers union and help local workers make their way onto the local education committee. These committees were often dominated by farm owners who sought to be sure that students were educated sufficiently to work on local farms but not much more. With such limited education workers and their children often lived in squalid conditions and they often took children out of school whenever seasonal cheap labor was needed, thus hampering their education further.

By 1911 the Higdon’s work created a rift in the local community and they were dismissed. It was at this time that they moved south to Burston. In Burston the Higdons arrived and took up the posts of School Mistress and Assistant Master. Tom also served as a Methodist lay preacher. In this part of rural Norfolk the squires and farmers ruled and held sway over the workers, who were expected to work for very low wages–often barely enough to live on with both pay and living conditions at an appalling level. Housing was atrocious and people died because of conditions. The local rector’s salary was 15 times that of the average local worker.

Like Aylsham, the Higdon’s encouraged the workers to take matters into their own hands, especially through changing the Parish Council. It was the Parish Council that set the rates of pay for field workers. In 1914 the local workers were able to assume full control of the council after a full slate of local hands were elected. In response to their agitation the Higdons were removed as teachers by the local school council, a council still under the control of the farm owners. It was their removal that sparked the school strike.  The school children marched to express their frustrations. The Higdons continued to teach the children on the local village green. To quell the defiance the school board took parents to court and fined them for failing maintain the enrollment of their children in school. When this didn’t succeed workers were evicted from their homes. The rector evicted workers from the land they rented to grow vegetables. Even the local Methodist minister was censured for aiding the students and their families. Eventually the students and teachers moved into local workshops and a “free” school was built and opened in 1917. It remained a “school of freedom” until 1939 when Tom Higdon’s death in 1939 when Kitty could no longer keep the school open.

The school children marched to express their frustrations. The Higdons continued to teach the children on the local village green. To quell the defiance the school board took parents to court and fined them for failing maintain the enrollment of their children in school. When this didn’t succeed workers were evicted from their homes. The rector evicted workers from the land they rented to grow vegetables. Even the local Methodist minister was censured for aiding the students and their families. Eventually the students and teachers moved into local workshops and a “free” school was built and opened in 1917. It remained a “school of freedom” until 1939 when Tom Higdon’s death in 1939 when Kitty could no longer keep the school open.

The story of the strike is told in the 1985 film The Burston Rebellion directed by Norman Stone, whose papers are housed in the Special Collections.