Chicago has always been seen as a rough-and-tumble kind of place stuck in the center of this country’s vast agricultural region and far short of the glories of the refined cities of either coast. The former stockyards of Chicago reinforced this. It is said that Chicago’s name can be traced back to native peoples and their name for the wild onions found locally. Onions are grown and mired in mud and muck and this is not too far from an apt description of Chicago’s history.

In the dozen or so years around the turn of the twentieth-century several individuals and writers sought to chronicle and clean up the filth of Chicago. The key event that afforded the opportunity for much of the work was the World’s Columbian Exposition in 1893. Having worked in Chicago for several decades during his worldwide evangelistic ministry, Dwight Lyman Moody held evangelistic meetings for six months during the “fair.” His campaigns have been detailed in Moody in Chicago (1894).

Whereas Moody was the evangelist, William T. Stead was the journalist. His chronicling of the religious needs of Chicago were quite different. Though Moody garnered the public’s attention it was never through outlandish acts or prurience. The same cannot be said for Stead’s provocative work If Christ Came to Chicago. Stead had come to Chicago from London as the fair was closing up. He was known as a great reporter and social reformer and had come to Chicago to study its newspapers, but the exposition’s great White City caught his attention. The thought of its destruction seemed too much and Stead sought to preserve the glories created there. As Stead remained in Chicago his eyes caught sight of another Chicago. Rather than the gleaming purity of the White City he saw the filthy darkness of the Black City that was in need of social and civic regeneration. In all his travels he had never encountered a city with greater promise, or problems.

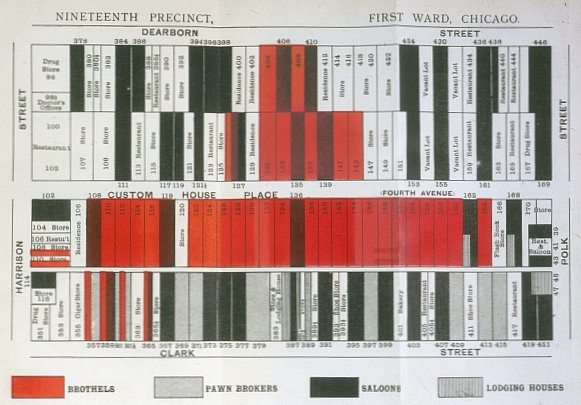

The closing of the fair had left many out of work and the economy of Chicago, previously propped up by the fair, tumbled into an economic depression. The great needs that emerged also facilitated an environment filled with licentiousness and debauchery. Stead wrote If Christ Came to Chicago to document the specifics of this environment and mapped it out with great specificity in Chicago’s First Ward. This laid the groundwork for future ethnographic studies of Chicago, most notably the work conducted by Hull House.

The closing of the fair had left many out of work and the economy of Chicago, previously propped up by the fair, tumbled into an economic depression. The great needs that emerged also facilitated an environment filled with licentiousness and debauchery. Stead wrote If Christ Came to Chicago to document the specifics of this environment and mapped it out with great specificity in Chicago’s First Ward. This laid the groundwork for future ethnographic studies of Chicago, most notably the work conducted by Hull House.

By writing this book Stead hoped to enlist the help of Chicago’s churches, the labor unions, and millionaires, many of whom, he felt, had neglected their Christian duty to the poor. His jeremiad was written to incite action. It certainly incited a public response, especially the book’s map of the location of bordellos, saloons, and pawn brokers.

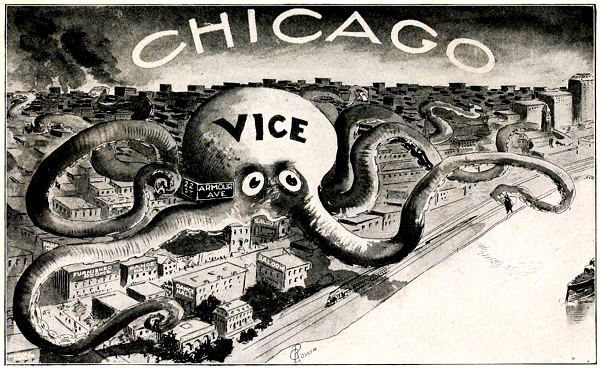

Despite Stead’s goal of bringing together a “union of all who love in the service of all who suffer,” the dirt wasn’t easily shaken from the wild onion. The roots of the onion are many. Nearly a decade and a half after the close of the Columbian Exposition it was still quite easy to document the problems of Chicago. The Social Evil in Chicago (1911) was a study conducted by the city’s Vice Commission and served as it’s report to the Mayor and city Council “of exciting conditions” in Chicago. The conditions of Chicago had not improved and in some ways were normalized and facilitated as can be seen by the official licensing of prostitution within the bounds of Wentworth and Wabash avenues (p. 38).

Despite Stead’s goal of bringing together a “union of all who love in the service of all who suffer,” the dirt wasn’t easily shaken from the wild onion. The roots of the onion are many. Nearly a decade and a half after the close of the Columbian Exposition it was still quite easy to document the problems of Chicago. The Social Evil in Chicago (1911) was a study conducted by the city’s Vice Commission and served as it’s report to the Mayor and city Council “of exciting conditions” in Chicago. The conditions of Chicago had not improved and in some ways were normalized and facilitated as can be seen by the official licensing of prostitution within the bounds of Wentworth and Wabash avenues (p. 38).

Chicago can still be described in many of the same ways as these texts from a century ago. The corruption of Chicago’s First Ward has been the fodder of newspaper accounts in recent decades. It still could use a “union of all who love in the service of all who suffer.”