I am composing these words at an altitude of 31,000 feet. After attending a four-day conference on teaching writing to undergraduates, I’m flying home. My mind feels like a suitcase packed full of new clothes; many fresh and colorful ideas are returning with me as a result of my participation in various lectures, workshops, and discussions.

Of all the subjects in English that I teach at Wheaton, courses in writing thrill me most. Yet, I must admit that my calling to the composition classroom exhibits a bit of God’s ironic humor: when I was an undergraduate, I loathed writing papers. Breaking a bone or catching a virus seemed like more tolerable experiences at the time. The task of putting words onto a page usually filled me with intense anxiety.

My frustration had little to do with the fact that I lacked a computer with a spell-checker; somehow I managed to type all of my college papers on a manual Smith-Corona, with a well-worn edition of Webster’s dictionary nearby (though I’m certainly grateful for my PC today). Nor did my travail result from a lack of scholastic interest or effort; as a new convert to Christ, I truly believed that the world–in all of its sadness and splendor–should he seriously studied because God made it.

My struggle, I now realize, came from my incomplete understanding of the purpose and practice of writing. As I then perceived it, the main reason I wrote papers was to show my professors two things: first, that I understood the subject matter of their courses, and second, that I understood how to craft my thoughts into grammatical sentences. Consequently, I tended to see writing as a skill primarily concerned with correctness. With each sentence, typically written at a snail’s pace, I asked myself, “Is this right?” And often, a voice inside my head would shout back, “No!” So, I would scratch out the sentence I had just written, and try to write a new one. My preoccupation with correctness paralyzed me.

In her essay, “The Watcher at the Gate,” Gail Godwin explains that most writers have an internal critic, an unrestrained negative voice committed to one goal: “rejecting too soon and discriminating too severely.” In describing her own Watcher, Godwin reveals one of her characteristic messages: “‘What’s the good of writing out a whole page,’ he whispers begrudgingly, ‘if you just have to write it over again later? Get it perfect the first time!'”

Now, as I teach my students how to write, I try to disabuse them of the myth that good writers get it perfect the first time. A great writer becomes great not because of inspiration, but because of dedication and perspiration. For example, I remind them that Thomas Jefferson carefully drafted the Declaration of Independence several times before it was finished, an accomplishment which he was prouder of than being the third President of the United States. Jefferson didn’t get his writing perfect the first time.

Instead of primarily focusing on the product of writing, I encourage students to consider the process of writing. Serious writers, more often than not, develop good habits that naturally foster good writing. They learn to observe, and to wait, and to receive; this approach requires a certain degree of humility.

Serious writers learn how to write when they don’t feel like writing, becoming obedient to the task at hand. They care about words as they think in ink. The novelist E.M. Forster explains, “How do I know what I think until I see what I say?” And after they have written something, they let other—those whom they trust—examine their work, and they actually welcome constructive criticism.

What’s more, they learn how to revise, which literally means to see again with new eyes; they accept the necessity of change.

In a real sense, the process of writing is analogous to the process of spiritual growth. Working with words demands discipline, which paradoxically sets us free to write well. So, too, living for the Word requires us to let go of our inclination to strive for our own perfection, which inevitably brings paralysis. We are asked, instead, to develop a habit of the heart, wherein we welcome the Word to dwell more fully in us. “In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God In Him was life, and that life was the light of men.”

———-

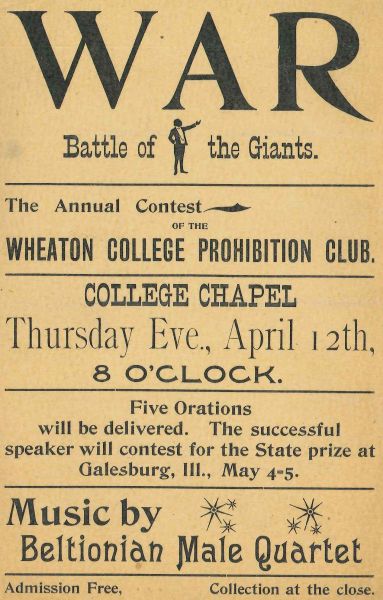

Twenty years ago, the Wheaton Alumni magazine began a series of articles, titled “On My Mind”, in which Wheaton faculty told about their thinking, their research, or their favorite books and people. Current Associate Professor of English, Jeffry Davis (on faculty since 1990) was featured in the Spring 1997 issue.

The following statement was included at the time of publication:

Dr. Jeffry C. Davis ’83 (Assistant Professor of English and Director of the Writing Center) has taught writing at Wheaton for more than a decade. He earned his M.A. in English from Northern Illinois University. Presently he is working to complete his Ph.D. at the University of Illinois at Chicago. His dissertation focuses on Quintilian, a first-century teacher of writing. In his spare time he gardens and listens to country music.