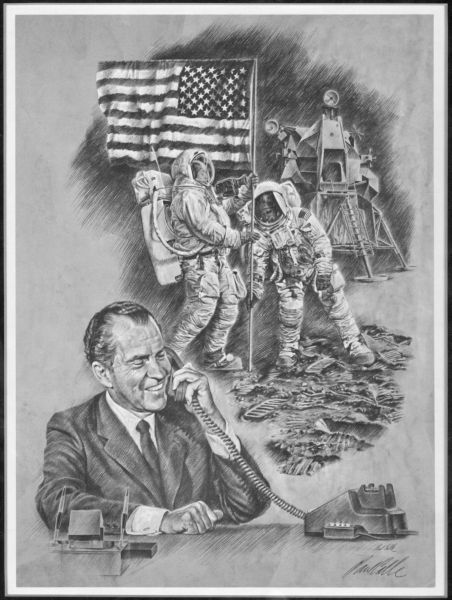

Among the numerous fascinating oddities stored in the Wheaton College Archives & Special Collections is this reproduction of an original drawing first presented to President Richard Nixon in Washington, D.C., in October of 1969, depicting the historic first telephone call to the Moon. The framed reproduction was presented to Dr. Hudson Armerding, President of Wheaton College, on January 16, 1970, by representatives of the Telephone Engineer & Management magazine. It is personally signed by artist Paul Calle.

Among the numerous fascinating oddities stored in the Wheaton College Archives & Special Collections is this reproduction of an original drawing first presented to President Richard Nixon in Washington, D.C., in October of 1969, depicting the historic first telephone call to the Moon. The framed reproduction was presented to Dr. Hudson Armerding, President of Wheaton College, on January 16, 1970, by representatives of the Telephone Engineer & Management magazine. It is personally signed by artist Paul Calle.

Monthly Archives: January 2015

Why Literature?

When I was a graduate student, I received a letter from my father that I will never forget. A career military man, he wrote in his typically clipped prose: “Explain terminal objectives of the Ph.D. in English.”

The question is not as hostile as it sounds. My father just wanted to understand why I was willing to endure a five-year diet of Ramen noodles. But the assumptions behind his question struck me. How could I explain to him that the study of literature exists, in part, to remind us that life is more than what can be measured by “terminal objectives”?

This truth has become central to my research concerns in recent years. Technologically advanced nations dazzle their citizens with dreams of genetically engineering children, escaping into virtual reality, perfecting the body, and even attaining immortality. Anyone who has followed the biotech and nanotech revolutions knows that these goals are not the stuff of science fiction only. And technocratic futurists like Ray Kurzweil try to make the desirability of these goals a given. What could be wrong with wanting children who are born without a genetic predisposition to cancer, they ask? Why not pursue the science of perpetually renewing, wrinkle-free skin? And if life is good, shouldn’t we all want to live longer, healthier lives?

While some might say that our rapidly changing biotech culture proves that the study of literature can be only an ivory tower indulgence, I believe that problems like these prove that we cannot afford not to study literature. Literature trains the moral imagination—that faculty that is uniquely able to challenge culture’s cherished assumptions. The moral imagination sees more broadly. It sees motives. It sees into the future—and into the past. It sees the potential for unintended consequences. It cautions us.

For example, Nathaniel Hawthorne’s story “The Birth-Mark” teaches us that behind the desire for beauty there may lurk a narcissism that is disdainful of real people. Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World teaches us that a social utopian’s vision of the good life might be, in fact, quite ugly. Margaret Atwood’s Oryx and Crake teaches us how our culture is shaping young people who, in the name of “progress,” see no problem with sacrificing humanity to attain it. Literary fiction can shock us into seeing the good, the bad, and the ugly—and the real difference between them. As Flannery O’Connor puts it, “I’m always highly irritated by people who imply that writing fiction is an escape from reality. It is a plunge into reality and it’s very shocking to the system.”

Why study literature? Because in some ways it has never been more important for us to know who we are-and where we are really going.

—–

Dr. Christina Bieber Lake, Associate Professor of English, received her Ph.D. in English from Emory University in Atlanta, and is associate professor of English, specializing in contemporary American literature. She is the author of The Incarnational Art of Flannery O’Connor, and is currently investigating American fiction’s engagement with posthumanism. She enjoys this excuse to watch Star Trek and to write about cyborgs, clones, and artificial life. Christina and her husband, Steve ’91, recently added their son, Donovan, to the family. All three eagerly await a Chicago Bears Super Bowl victory. (The above statement was included at the time of publication — Wheaton Magazine, Winter 2007)

Selma and Wheaton College

The release of the 2014 film Selma, produced by Oprah Winfrey, has stimulated renewed vigorous conversation regarding the efforts of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. and the development of the Civil Rights movement. This article from the March 19, 1965 issue of The Record chronicles the brief but impactful journey of two Wheaton College students to those momentous events.

Two Wheaton seniors joined 2500 other civil rights demonstrators in Selma, Alabama, a week ago Tuesday as they marched with Dr. Martin Luther King up U.S. Route 80 to the place where state troopers turned them back without incident. Leaving Wheaton Monday, March 8, after hearing of the brutalities Sunday afternoon, Randy Baker and Bob Vischer arrived in Selma by 11 a.m. Tuesday, March 9. Explaining their motives for going, Vischer said, “I could think of no better way to express my concern than through action.” Upon their arrival in Selma, they found several hundred Negroes and whites – citizens, students, clergy, newsmen and polices – gathered in front of Brown Chapel. Entering the church, where another group of 300 to 400 were gathered, they heard various speakers, including many prominent religious leaders, talk for two or three hours.

As they left the church after Dr. King’s final admonitions, said Vischer, they were given instructions by a medical doctor as to precautions in case they should be tear-gassed, knocked unconscious or hurt with broken bones. As he and Baker marched in the front-quarter of the line, which ran four-abreast, someone told Vischer to take off his glasses. For the first time, he realized the real possibility of physical harm. “I began to see a little of the importance which the people of Selma and others in the march attached to the obtaining of equal rights,” he commented.

Confronting the state police about 200 yards across the Alabama river, King decided they would have a service of prayer and singing there instead of attempting to march through to Montgomery, having been influenced by federal mediation. After singing several verses of “We Shall Overcome” and listening to the prayers of several clergymen, the demonstration turned back to Selma. As they marched both to and from the place of confrontation with the troopers, Vischer recalled, “There was the knowledge that each of the 2500 in the march was dead serious about his task of bringing this injustice before the eyes of the nation and the world and that each was willing to risk death for this.”

After the march had been completed, Baker and Vischer encountered further danger as they went downtown to pick up their car to leave. As the two walked alone down the sidewalk, four white men stepped in front of them and asked where they were marching. Vischer stepped back and replied that they were not marching anywhere. But Baker, who did not step back, was grabbed by the largest and slugged on the side of the head. After Baker had pulled his coat away, the two started a fast walk across the street, but changed when they saw more men on the other side. “At this point,” remarked Vischer, “I felt I could empathize with the Alabama Negro, for here I was being pursued, and with no place to turn to. We felt alone and weaponless. I have never been so frightened in all my life.”

Later, however, the two stressed that undoubtedly the majority of the people of Selma would not have used violence against them or against the Rev. James Reeb, the minister who was killed later that afternoon. Yet, they said, “The scum who carried out these activities are supported by the system which presently exists – and this system must be smashed by a bold show of Christian love.”

Walter A. Maier at Wheaton College

One of the renowned evangelists of the mid-twentieth century was Walter A. Maier (1893-1950), author, radio broadcaster and professor. Blessed with a sharp mind and clear voice, he hosted The Lutheran Hour from 1930-1950. Maier was closely associated with Concordia Seminary in St. Louis, where he taught Semitic languages. In addition to his administrative and pastoral duties, he traveled widely, advocating classic, conservative Christianity, preaching and teaching in churches, seminaries, festivals and schools, including Wheaton College.

One of the renowned evangelists of the mid-twentieth century was Walter A. Maier (1893-1950), author, radio broadcaster and professor. Blessed with a sharp mind and clear voice, he hosted The Lutheran Hour from 1930-1950. Maier was closely associated with Concordia Seminary in St. Louis, where he taught Semitic languages. In addition to his administrative and pastoral duties, he traveled widely, advocating classic, conservative Christianity, preaching and teaching in churches, seminaries, festivals and schools, including Wheaton College.

In 1940, the annual Washington Banquet was cancelled; subsequently, Wheaton College students were encouraged by acting president V. Raymond Edman to contribute the money they would have spent at this event to the Christian Relief Fund for Finnish and Chinese Christians in war zones. Instead of the usual pageantry associated with the Washington Banquet, typically hosted at a local hotel, students met for an informal program in Pierce Chapel, where Walter A. Maier was the honored guest for the evening. Maier also occasionally preached chapels at Wheaton College.

True North

Market economies do an amazing job of providing goods and services that we enjoy on a regular basis. A stroll through your favorite supermarket, chain drugstore, or major department store—with countless products on display—clearly illustrates our grand array of choices. When we go to sleep at night, there are literally hundreds of millions of people around the world investing time and energy thinking about us, what we need and want, and how they can produce those things.

I get excited when I can help students appreciate the power of economic forces and understand how market economies work. But at the core of any market system is a concept of value that is egocentric, humanistic, and relativistic. Markets are defined by a sense of value that says, Things are worth what I say they are worth. This poses no little challenge to a Christian professor of economics.

I have come to believe that your greatest strength can also be your greatest weakness, and sometimes a real weakness, in another context, can actually work for you. Such is the case, I believe, with marketplace morality. The greatest weakness of markets is they are morally neutral—they can’t distinguish between penicillin or pornography, peanuts or prostitution, housing or heroin. In 2004 Americans spent $92.8 billion on gambling as compared to $38.7 billion on computers and peripherals. But markets are excellent mirrors for reflecting whatever values people bring to them. If we bring the right values to the marketplace, then that is what will be reflected back to us in the form of goods and services.

Over the last several years, I’ve been trying to synthesize a list of values that transcend pure economic individualism. Are there values that everyone can agree and aspire to? I offer these twelve:

• People are more important than things.

• Treat others as you want to be treated.

• Truth matters at all levels.

• Leave things a little better than you found them.

• People are looking for a cause to live for that is larger than themselves.

• Let freedom ring. (In the best companies, people don’t feel like slaves. They feel that they can have influence.)

• Community counts.

• Good laws will outlive good men.

• Value vocation. (Decide who you want to be, and let that drive what you do.)

• Life is a mix of duty and delight.

• Choice has consequence.

• Keep the core when all else is changing. (People will be better positioned to accept change when they know something isn’t changing fundamentally.)

I’m not suggesting that people have embraced these values to the point where they are fully integrated into economic activity, but people do want to live in an economic world where critical transcendent values operate throughout the system. This requires economic leadership, and leaders who know where to go. Our desire at Wheaton is for students to graduate with a recognition of knowing how to find “true north,” a keen sense for moral direction. It is the only way we can be truly pleased with all the outcomes of the marketplace.

—–

Dr. Bruce Howard ’74, Professor of Business & Economics, is chair of the business and economics department of Wheaton College. He is a CPA, and earned his Ph.D. in economics and his M.S.A. in accounting from Northern Illinois University. Dr. Howard enjoys spending time with his family, and his hobbies include art, music (guitar and banjo), and playing tennis. He is also currently working on a book that elaborates on his 12 values for a moral marketplace. (The above statement was included at the time of publication — Wheaton Magazine, Winter 2006)