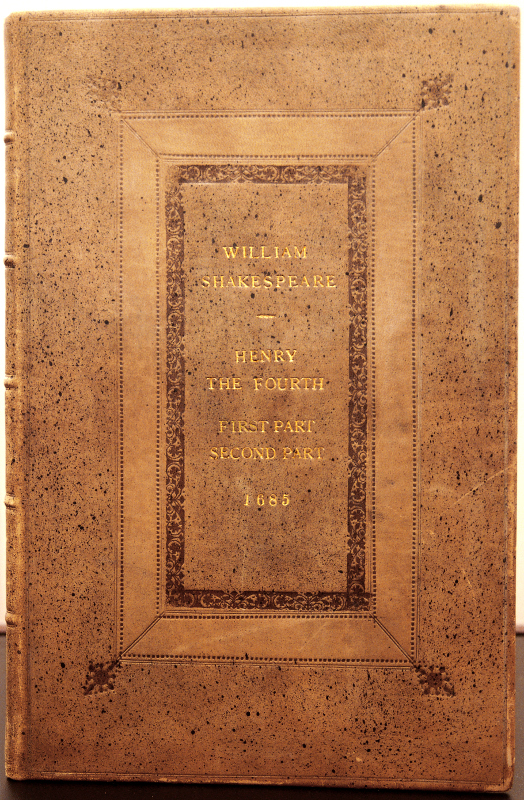

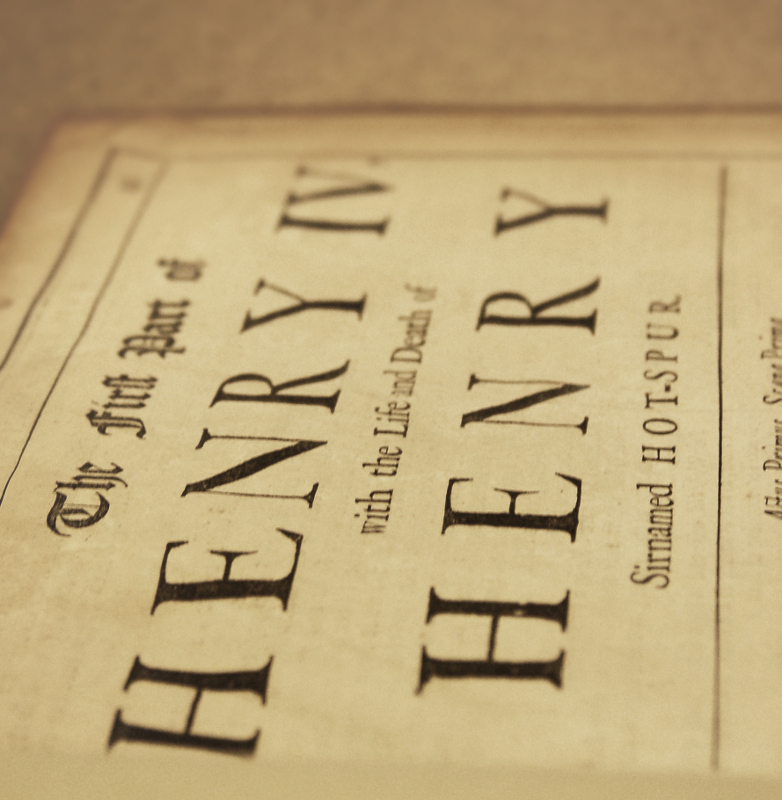

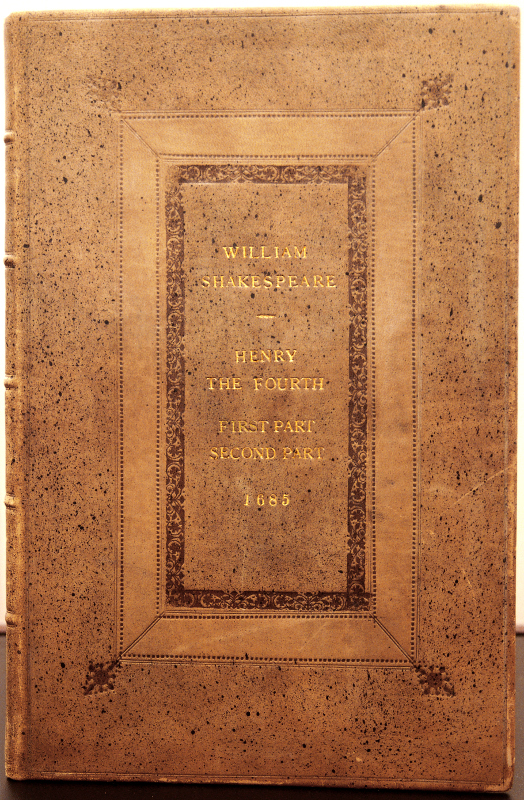

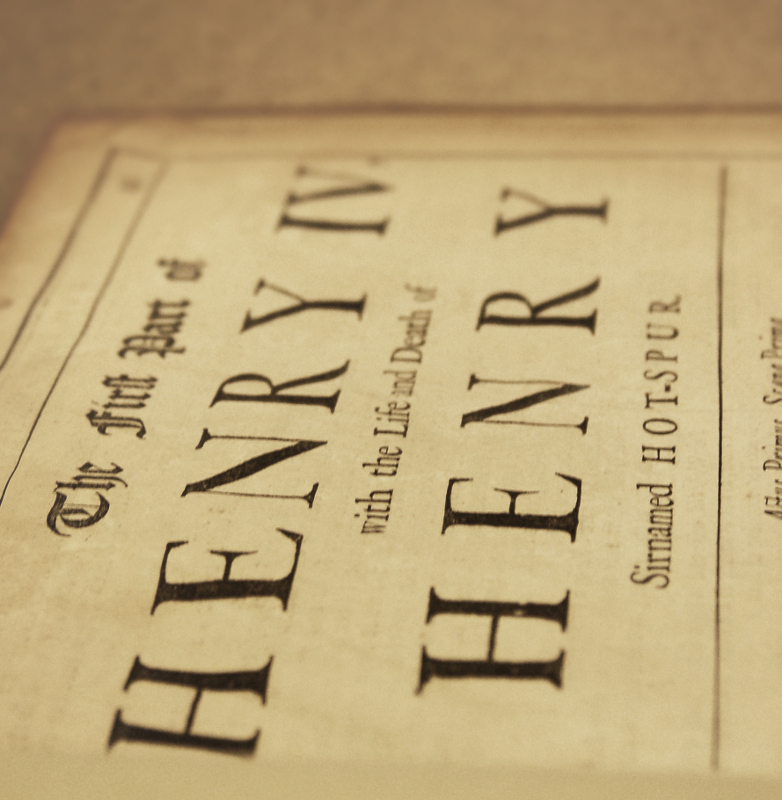

As part of the E. Beatrice Batson Shakespeare Collection in the College Archives and Special Collections, Buswell Library is pleased to have a copy of Henry the Fourth, both the first and second parts. These plays are taken from the fourth folio edition of Mr. William Shakespear’s Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies (1685) and were donated to the College in honor of Dr. Batson’s retirement from the English Department about 25 years ago. This month, thanks to the generous donation of a custom-made case, our folio has found a new home on permanent display in the lobby of Buswell Library.

As part of the E. Beatrice Batson Shakespeare Collection in the College Archives and Special Collections, Buswell Library is pleased to have a copy of Henry the Fourth, both the first and second parts. These plays are taken from the fourth folio edition of Mr. William Shakespear’s Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies (1685) and were donated to the College in honor of Dr. Batson’s retirement from the English Department about 25 years ago. This month, thanks to the generous donation of a custom-made case, our folio has found a new home on permanent display in the lobby of Buswell Library.

In preparation for this display, I had the opportunity to research this special book, and the findings were rather surprising.

***

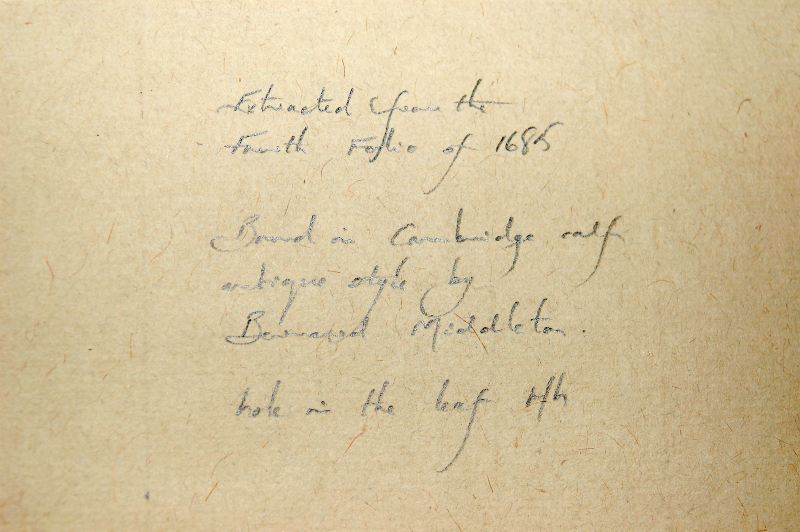

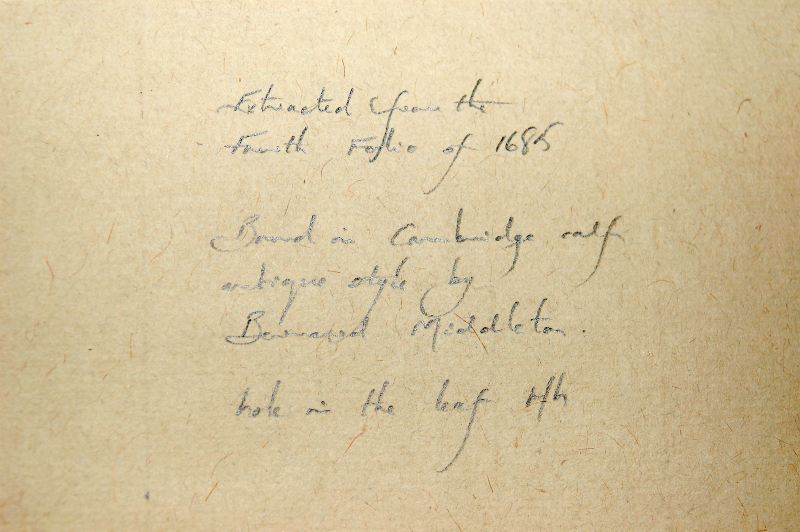

At first, all we knew about this volume was contained in an inscription written in an unknown hand on one of its back fly leaves:

“Extracted from the / Fourth Folio of 1685 / Bound in Cambridge calf / antique style by / Bernard Middleton. / hole in the leaf Hh”

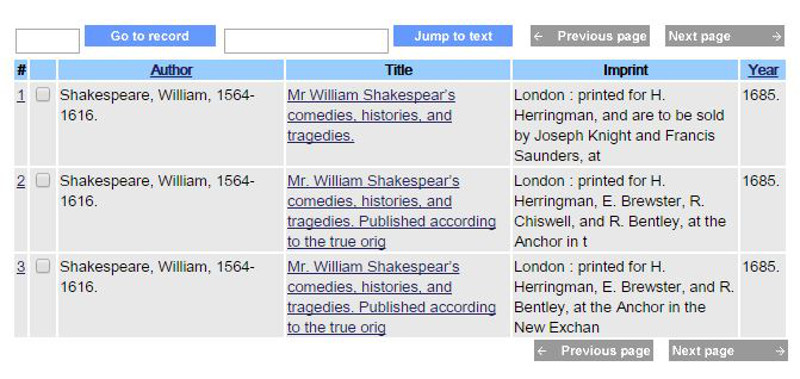

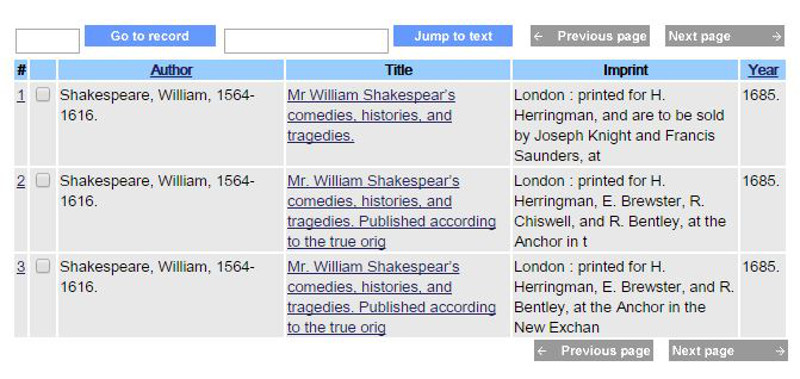

I was able to locate the publication information for the “Fourth Folio of 1685” through the English Short Title Catalogue, a database of antiquarian English books hosted by the British Library. A combined author and date search returned three entries:

Without a title page, it was impossible to tell which of the three imprints our plays contained. Therefore, as “H. Herringman” was the only constant between the three, he was the obvious starting point for further research.

The British Book Trade Index and CERL Thesaurus list “H. Herringman” as Henry Herringman, who worked from 1653-1693 as a bookseller and publisher in London. He specialized in producing fine literature and dramatic texts, which is unsurprising considering his relationship with the poet John Dryden and his many copyrights for Shakespearean works.[1]

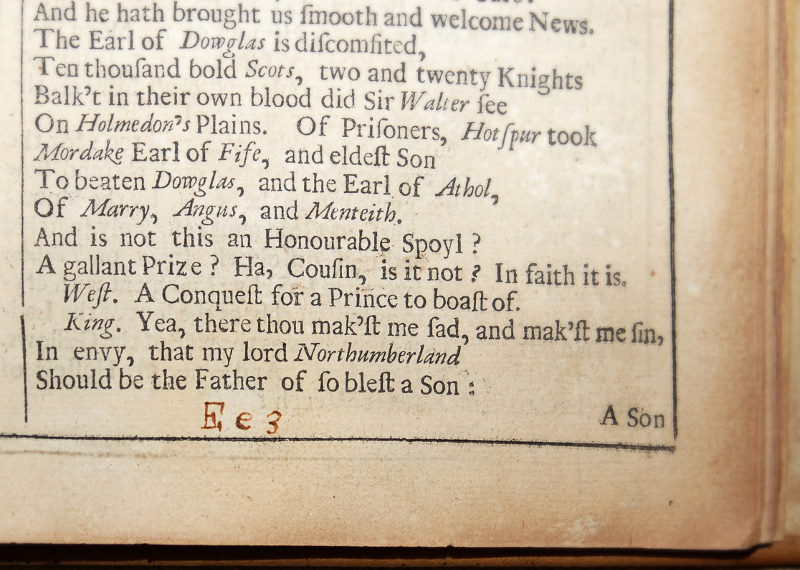

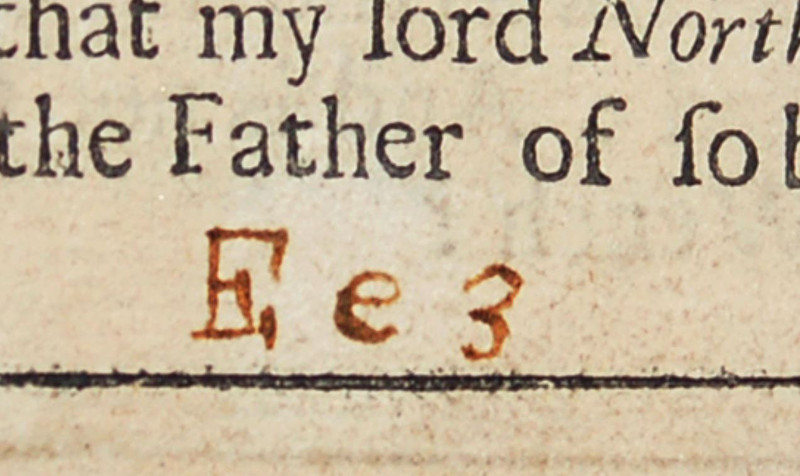

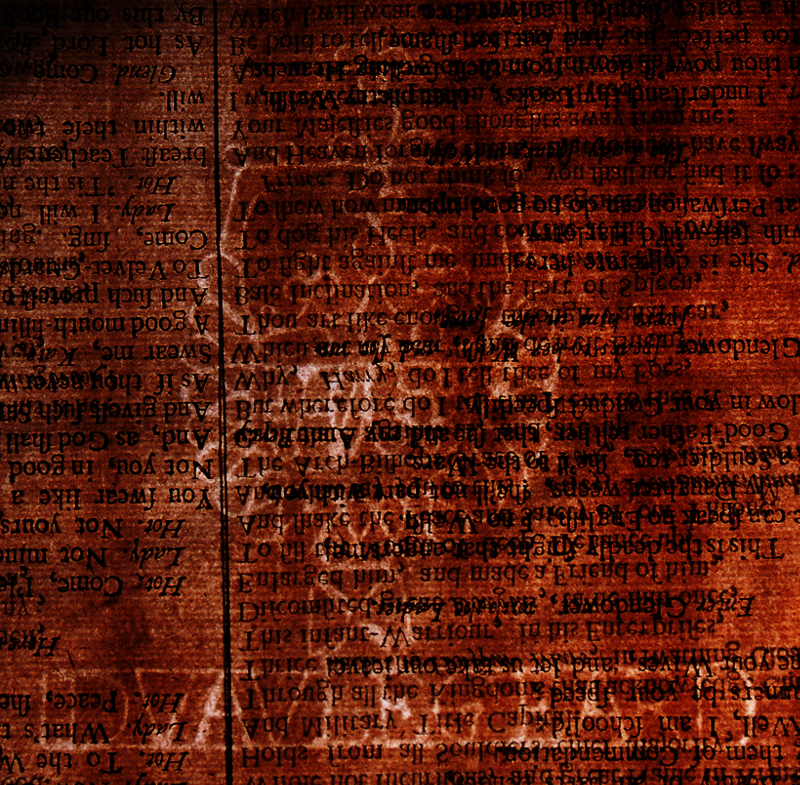

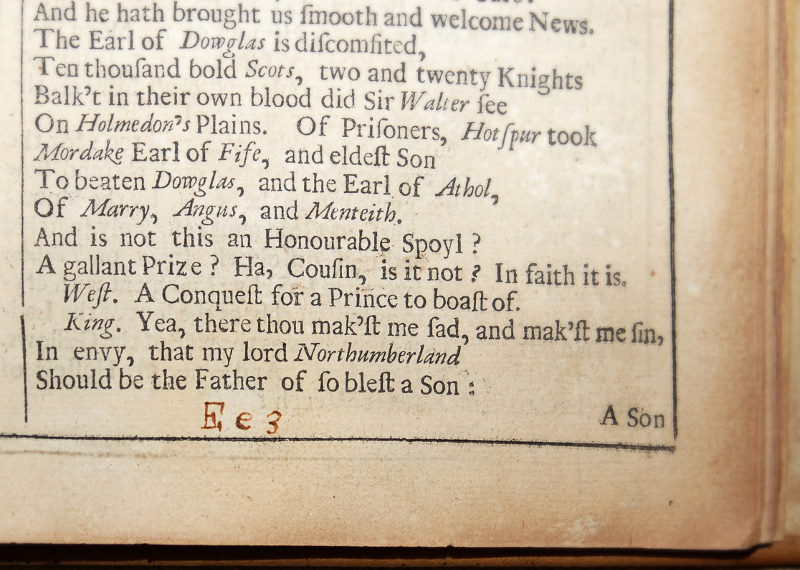

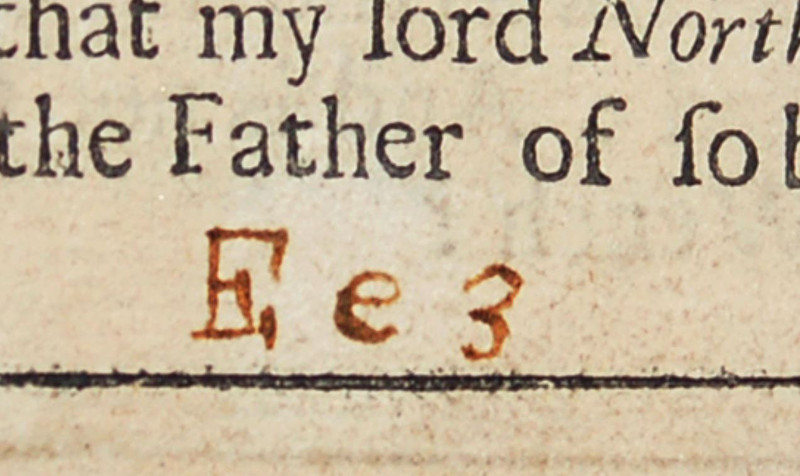

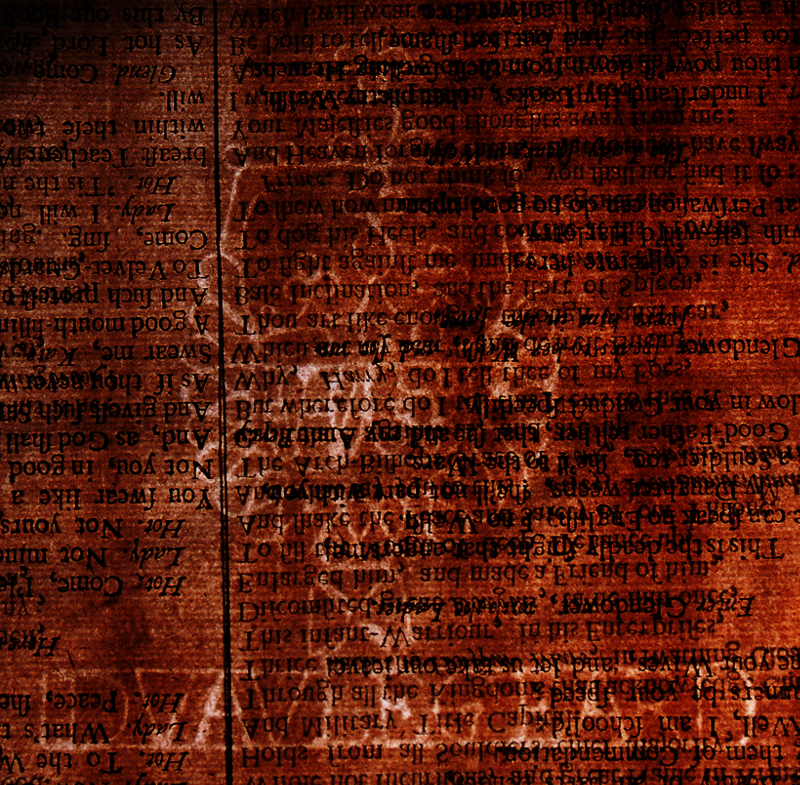

To publish Shakespeare’s fourth folio, Herringman employed three printing houses to each produce a section of it. The plays in our copy are taken from the second section, which is particularly interesting due to its errors in layout. More specifically, there were many mistakes made in labelling the signatures. These combinations of letters and numbers in the bottom right corners of certain pages determined the format of the book, and so it was important that they be precise. Our copy of The First Part of Henry IV features an example of such an error on folio 41: the signature “Ee3” had been mistakenly left off the page, but here someone (likely from the printing house) has corrected it by hand with ink.

Scholar Giles E. Dawson examined nearly 40 copies of this folio, and in the majority of them “Ee3” was added in this way. He notes that the handwriting is the same in all the copies he examined, and that it is most distinctive in this particular signature.[2]

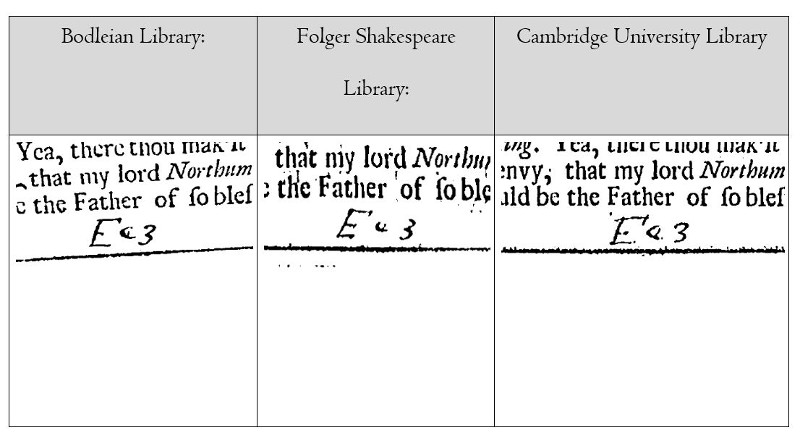

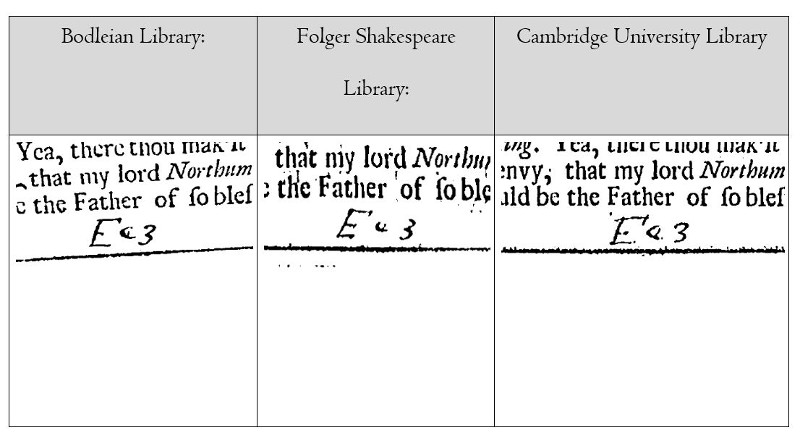

Having read Dawson’s assessment, I wanted to compare our signature to that in others copies and see if it matched. The ESTC linked to three examples of this text, one with each of the different imprints, in the Early English Books Online database and it seems Dawson was correct: in all of them, there is a forward slant in the uppcase “E” and the crossbar of the lowercase “e” is tilted upwards.

Ours, however, appears different:

The uppercase “E” has no slant to it (although it certainly has some ungraceful serifs), and the crossbar on the lowercase “e” is flat. Was it written by someone else? Or could the corrector have been experimenting, perhaps using a different pen?

***

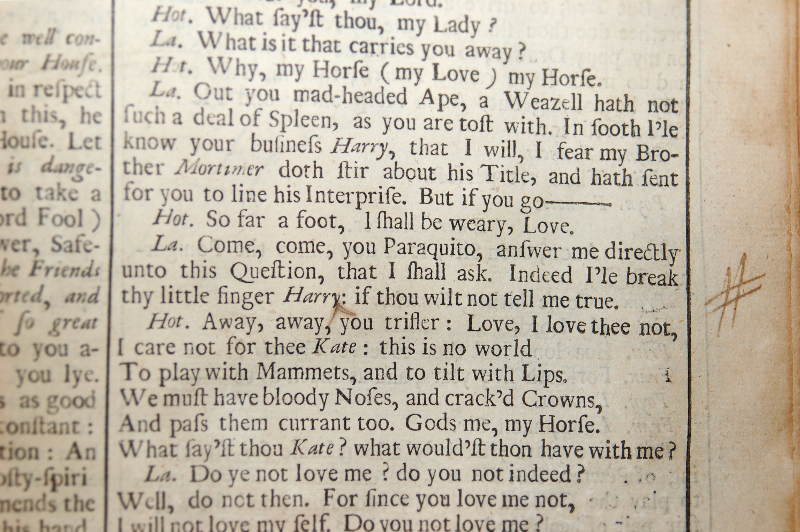

In another place in the book, we find more markings and they, too, highlight some strange particularities.

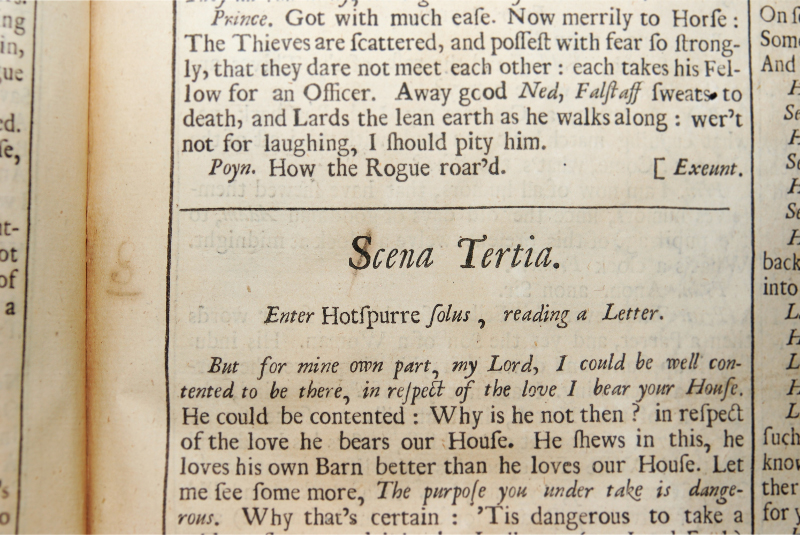

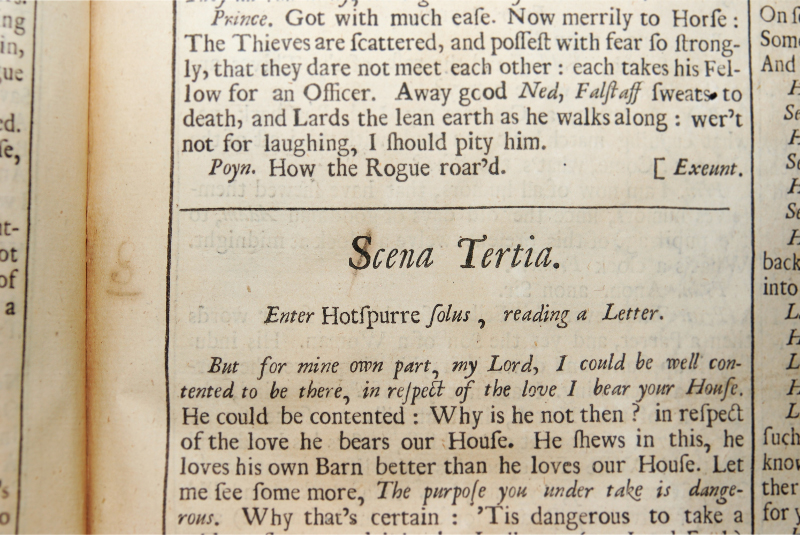

Folio 47 features parts of two scenes from The First Part of Henry IV which someone has marked up to note typographical and editorial issues. For example, the “S” in “Scena Tertia” is incorrectly printed in roman, while the rest of the heading is italicized:

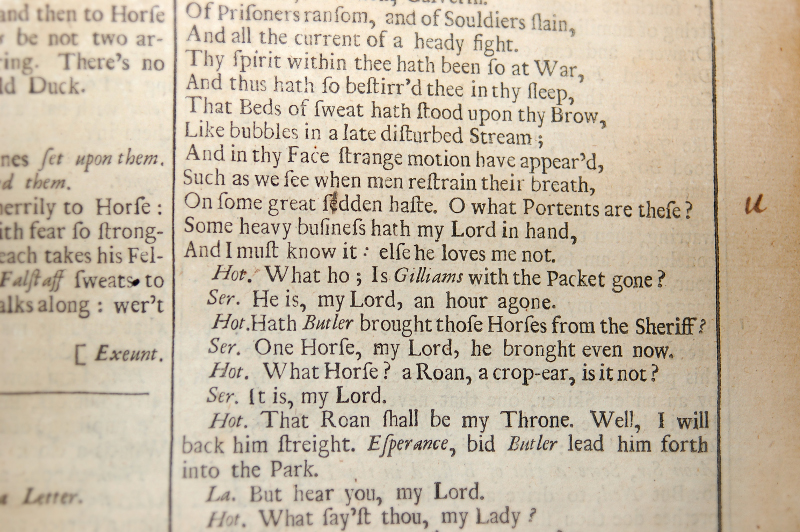

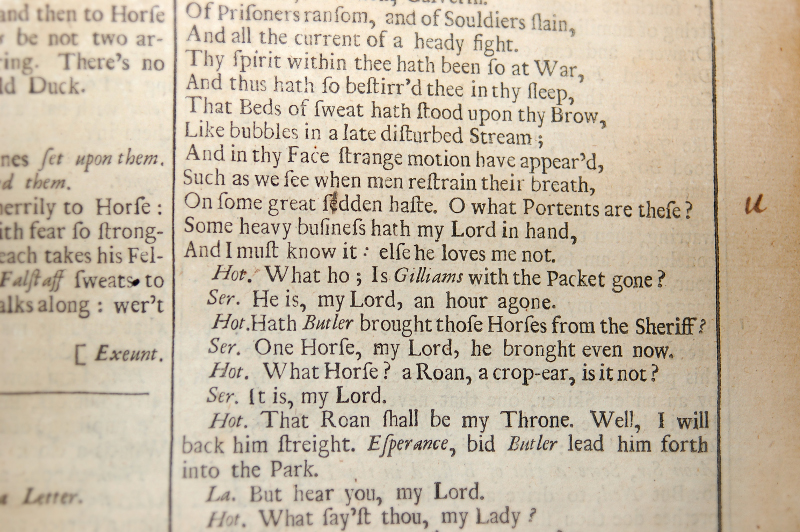

On the other side of the page, a misspelling is noted, where the “e” in “sedden” is crossed out and the correct letter, “u”, is written in the margin:

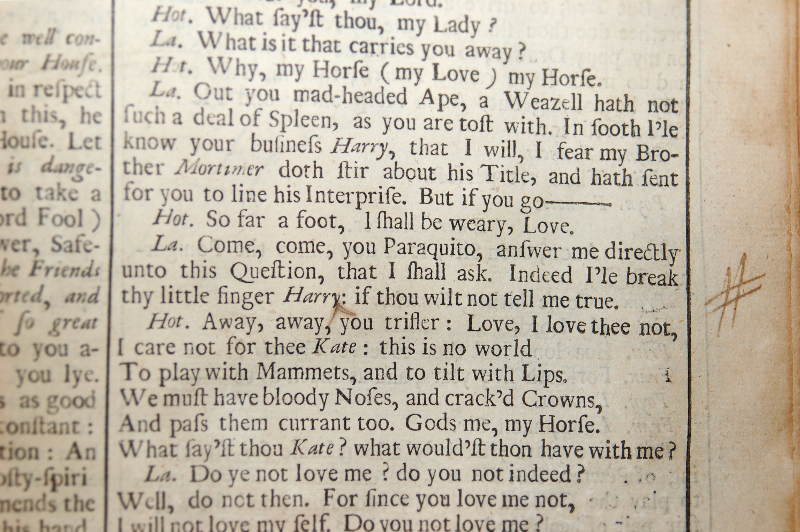

And below that, a pound sign in the margin corresponds to a marking within the text:

This was a convention with which I was unfamiliar. One of the pound sign’s many purposes over time has been to signal the need for a space, which seems to be the significance here. In an attempt to date these notations, I tried to research the history of the pound sign as an indicator of a missing space. While the history of marginal and typographic symbols has been the topic of several books and blogs in recent years, writers have focused on the pound sign’s capacity as an abbreviation for, well, “pound” rather than as an indicator of a lacking space. As a result, I’m uncertain as to when this became common in proofreading, which makes it difficult to determine when these notations were added.

That said, there are two remarks that can be made with certainty. The first is that all of the Shakespeare folios were printed at a time when the English language was yet unstandardized and undergoing continual changes in spelling and punctuation. Each was edited differently, although compositor’s mistakes were to blame as well as emerging conventions.[3] The marks in our volume illustrate one person’s engagement with his or her text in a period where readers, writers, and compositors were experiencing a dynamic evolution of language.

A second certain remark is that none of the other aforementioned copies of the fourth edition have these mistakes on this page. The books at the Bodleian Library, Folger Shakespeare Library, and Cambridge University Library all have the italic “S” instead of the roman, the correct “u” in sudden, and while the quality of the EEBO scans makes it tricky to determine for sure, it seems as though all also have a space between “Henry” and the colon.

What does this indicate? To be honest, I’m not sure. Could these markings signal a printer’s copy used to make changes before sending the book to press? It’s possible, although one would assume that the errors in layout would have been flagged then, too.[4] The general design of the page is consistent with that of the fourth edition and only the fourth edition of the Shakespeare folios, leaving me frankly quite puzzled as to where this copy fits into the larger narrative of the publication. Between the differences in the signatures and now this page, our book contains some mysteries which, until further research is completed, must remain unsolved.

***

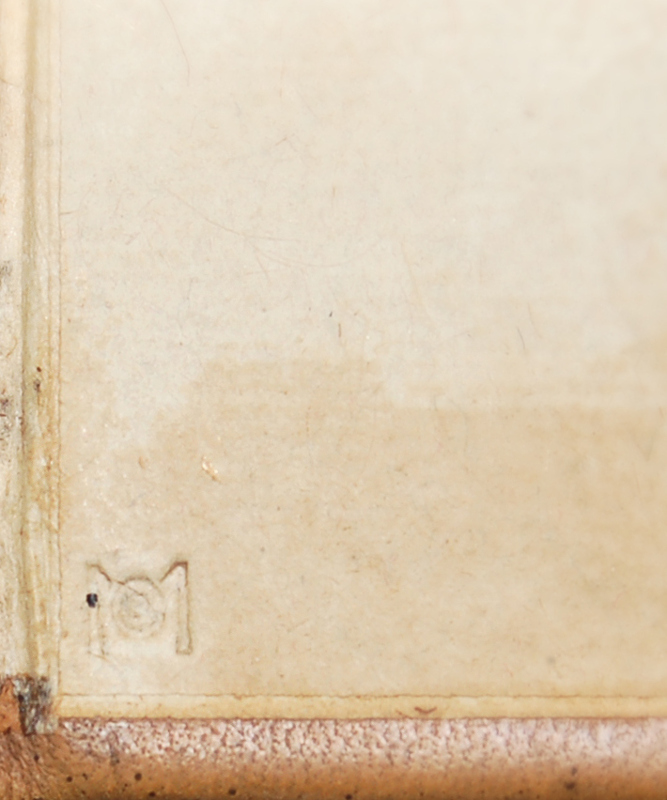

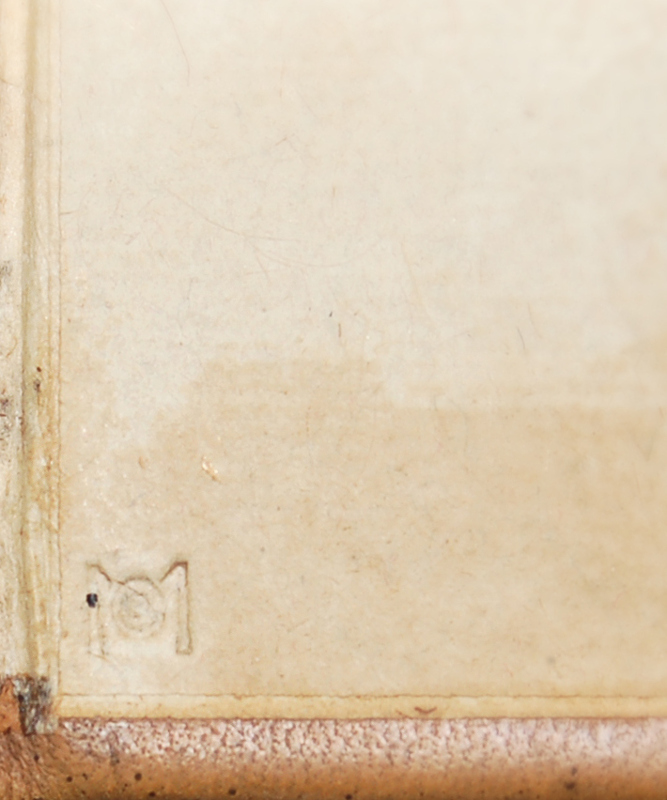

The material composition of this book, on the other hand, is a mystery solved. As stated in the inscription, our copy was specially bound by Bernard Middleton, a renowned British binder who flourished in the twentieth century and literally wrote the book on English bookbinding. The work he did for our copy resulted in an elegant speckled calf leather binding with blind tooling and gilt letters, and he signed his work in the lower left corner of the back cover paste-down using his signature stamp.

Determining the papermaker, on the other hand, was a bit trickier. Such details aren’t listed in imprints and there was nothing in the inscription. Yet when held up to the light, it became clear that, consistent with folios from the era, our book was printed on antique laid paper with vertical chain lines. Upon closer inspection, I saw a watermark:

It was hard to make out the letters and shapes, but I saw something resembling a plus sign, a possible fleur-de-lis, and the letters V, A, and L towards the beginning of the word and A, R, and D towards the end. It looked like “OVALGARD”, but this search returned no results. While browsing the Thomas L. Gravell Watermark Database, however, I discovered the name of a seventeenth-century papermaker from Normandy, Denis Vaullegeard, who sometimes used the spelling “DVAVLEGEARD” in his watermarks. As it happens, Dawson had already credited Vaullegeard’s work on the fourth folio paper in an article published more than 50 years ago. According to him, multiple Vaullegeard watermarks are found on the pages of the folio, all containing elements featured in the image above: the name, the shield, and the loopy ribbon bordering it.[5]

***

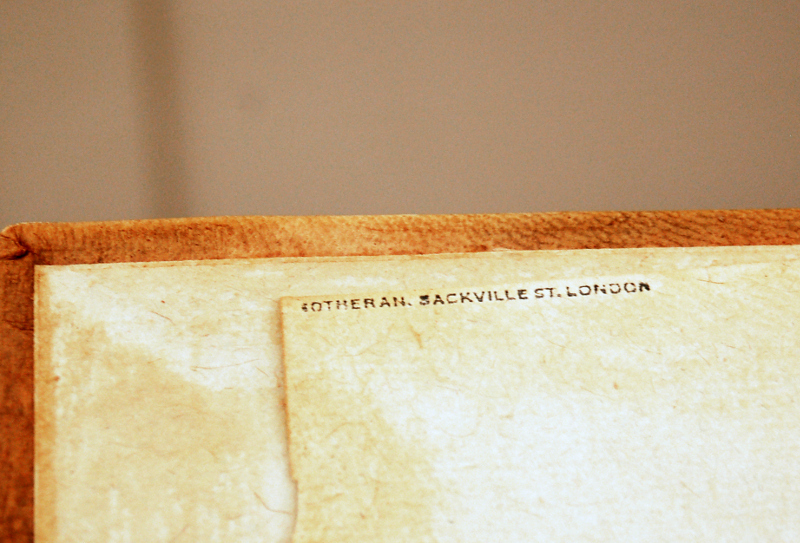

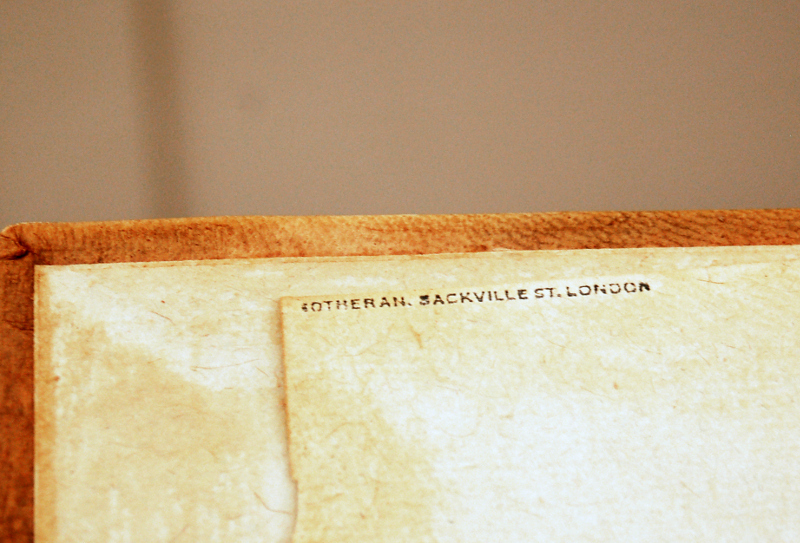

A final clue also appeared on the paper, and while it wasn’t quite as hidden as the watermark, it still originally passed unnoticed. In the top left corner on the back side of the front free endpaper are some tiny words in ink:

Thanks to a quick Google search, what looks like “LOTHERAN. JACKVILLE ST. LONDON” was revealed to be “SOTHERAN SACKVILLE ST. LONDON”. Sotheran’s of Sackville Street is, according to its website, the oldest antiquarian bookshop in the world, founded in York more than 250 years ago.

Since our provenance information for this item is limited, I emailed Sotheran’s for more information and quickly received a reply from the Managing Director. He informed me that they have sold many plays taken from (typically incomplete) copies of all four folios, and while he wasn’t able to locate the information for our particular plays, he was able to tell me that they must have been sold after 1936, the date in which Sotheran’s moved to Sackville Street. Their archives were destroyed in World War II—bombing and looting during this period have created numerous provenance problems—so it may be that our plays were sold in between those events and the record is gone, or they might have been sold later and Sotheran’s records database is incomplete. Regardless, we now have some insight into the three centuries between our book’s publication and its arrival in the College Archives & Special Collections.

***

Although many details from our book’s past are still unknown, we were able to find out much about this special copy. Perhaps as more editions are digitized and more scholarship is completed, we will discover exactly why our copy stands unique among its peers, and maybe even find out more about its provenance. In the meantime, if you would like to see Henry the Fourth for yourself, please come visit the display in Buswell Library.

References:

[1] See Sonia Massai, “‘Taking Just Care of the Impression’: Editorial Intervention in Shakespeare’s Fourth Folio, 1685,” in Shakespeare Survey Volume 55: King Lear and its Afterlife, ed. Peter Holland (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 257-270; and Giles E. Dawson, “Some Bibliographical Irregularities in the Shakespeare Fourth Folio,” in Studies in Bibliography, 4 (1951/1952), 93-103 for more information on Herringman and the production of this folio.

[2] See Dawson, “Some Bibliographical Irregularities,” 94.

[3] See Massai’s article, as well as Matthew Black and M. A. Shaaber’s book, Shakespeare’s seventeenth-century editors, 1632-1685 (New York, Kraus Reprint Corp., 1966), for details on the editorial process.

[4] Dawson notes that these layout errors were indeed noted late into the printing, and corrections were made for a small remaining batch of books which technically comprised a fifth edition; see “Some Bibliographical Irregularities,” whole article for more information.

[5] “Bibliographical Irregularities,” 246.

Charlie Brown, next to Mickey Mouse and Superman, is arguably the most iconic American comic strip character. Created by Charles Schulz, the Peanuts cartoon ran from October 2, 1950, to February 13, 2000. Amazingly, the final original strip appeared one day after the death of Schulz.

Charlie Brown, next to Mickey Mouse and Superman, is arguably the most iconic American comic strip character. Created by Charles Schulz, the Peanuts cartoon ran from October 2, 1950, to February 13, 2000. Amazingly, the final original strip appeared one day after the death of Schulz.He put a little sad face on the circle, drew a much-too-small body under it and introduced Charlie Brown. Then he covered the drawing with vertical streaks. “That’s rain,” he explained. Charlie Brown says, “It always rains on the unloved.”

As part of the E. Beatrice Batson Shakespeare Collection in the College Archives and Special Collections, Buswell Library is pleased to have a copy of

As part of the E. Beatrice Batson Shakespeare Collection in the College Archives and Special Collections, Buswell Library is pleased to have a copy of