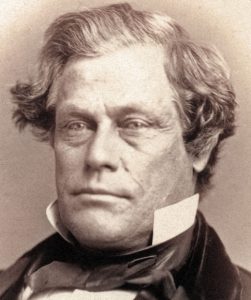

On November 23, 1859, the minutes of the Board of Trustees of the Illinois Institute, the precursor to Wheaton College, record that the Rev. Jonathan Blanchard opened the meeting in prayer and that seven new members joined the board. Among these founding Trustees of the soon-to-be-established college was Owen Lovejoy, the younger brother of martyred abolitionist Elijah P. Lovejoy. Owen was also a sitting U.S. Congressman from Illinois (who later introduced the bill to outlaw slavery in the United States) and an intimate friend of Abraham Lincoln.

Several years later during the annual trustee meeting of June 1864, Rev. Blanchard, now President of Wheaton College, proposed a new scholarship to honor Owen who had passed away the previous March. The Lovejoy Scholarships would support the education of students of color, and in his remarks about the fund, President Blanchard praised the work and character of his dear friend:

“As it has pleased our Heavenly Father during the last year to remove by death the Rev. & Hon. Owen Lovejoy, a member of this Board, we desire hereby to express our loyal and cheerful submission to the ordering of our Sovereign, infinitely wise and good, while we record our affectionate sorrow and our appreciation of the Christian, the philanthropist, the patriot, who has been removed from us in the meridian of his powers of his influence of his success.

As the life long champion of the despised slave he was worthy of our admiration and our affection. But to his principles of sympathy with everything, with everything that tended to abate from the spirit of caste and to promote a healthy public sentiment, he was willing to cast in his name and influence with this Institution, even when political honors, that had begun to rest upon him, might have tempted him to decline such a relation.

We will ever cherish the memory of his virtues, while we believe that the savor of his self-sacrificing life will be preserved as one of the rich legacies of our nation.

Whereas the Trustees of the Lovejoy Monument Association have proposed the endowment of Lovejoy Scholarships for the education of colored persons [sic] in such of our literary and professional Institutions as will receive the recipients of those funds to equal privileges and on the same terms with the white students.

Resolved, that this Board highly approve the proposed plan of perpetuating the memory of that Christian patriot, that true philanthropist Owen Lovejoy and that we proceed to the endowment of a scholarship of 1000 dollars upon the conditions required by the Monument Association and to be called the Lovejoy Scholarship.”

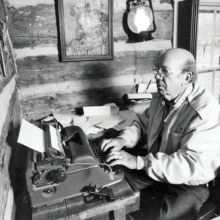

Presenting himself as a backwoods “bootleg” hayseed, wearing cowboy boots and straw hats, he actually possessed a fine intellect, abundant courage and quick wit. Campbell, siding unhesitatingly with the oppressed and disenfranchised, was one of four who boldly escorted African American students, known as the “Little Rock Nine,” into the racially segregated Little Rock Central High School in 1957. Campbell was also the only white man to attend the founding of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1957.

Presenting himself as a backwoods “bootleg” hayseed, wearing cowboy boots and straw hats, he actually possessed a fine intellect, abundant courage and quick wit. Campbell, siding unhesitatingly with the oppressed and disenfranchised, was one of four who boldly escorted African American students, known as the “Little Rock Nine,” into the racially segregated Little Rock Central High School in 1957. Campbell was also the only white man to attend the founding of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1957.