At first glance, Wheaton College in Wheaton, Illinois, and Fermilab National Accelerator Laboratory in Batavia, Illinois, share few points of commonality; but a closer examination reveals otherwise.

Wheaton College (est. 1860) and Fermilab (est. 1967) were intentionally situated on the largely undeveloped prairie about thirty miles west of Chicago for convenient access by cross-country traffic.

Both institutions employed talented veterans of the classified Manhattan Project, which eventually ended WW II. Dr. Robert Rathbun Wilson (1914-2000), Fermilab’s first director and guiding visionary, served as the head of R (Research) Division at Los Alamos, New Mexico, under the supervision of Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer, the “father of the atomic bomb.” Similarly, Dr. Roger Voskuyl (1910-2005), professor of Chemistry at Wheaton College and later president of Westmont College in Santa Barbara, California, served as a group leader for the top-secret mission.

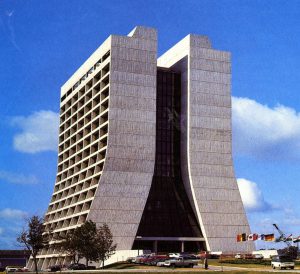

Administrative and academic activities for both campuses revolve around iconic loci featured on signage and letterhead. Fermilab’s Wilson Hall, aesthetically influenced by the gifted architect Robert R. Wilson, dominates the landscape at sixteen stories. The upward sweep of its outer walls, somewhat resembling praying hands, purposely evokes the Beauvais Cathedral in France, the most daring Gothic undertaking of the 13th-century.

Wheaton College’s neo-Gothic main building, Blanchard Hall, recalls structures admired by founder and first president Jonathan Blanchard during a European journey.

While Jonathan Blanchard was a rock-ribbed Yankee who protected escaped slaves via the Underground Railroad, Robert Wilson was a proud descendant of abolitionist John G. Fee, founder of Berea College, a school for blacks and whites in pre-Civil War Kentucky. Wilson also actively recruited people of color to work at Fermilab during the Civil Rights Movement.

Fermilab’s staggeringly complex machinery, particularly DUNE (Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment), is extensively networked beneath the farmland of Batavia, while the sandstone blocks used to construct Blanchard Hall were cut from a quarry in Batavia.

Both institutions boast pretty good cafeterias.

A herd of buffalo, brought by Wilson to recall his beloved childhood home in Wyoming, graze the high grasses on a ranch at Fermilab, while a gaggle of haughty geese strut freely through the manicured acreage of Wheaton College.

Fermilab educates students, scientists and engineers from all over the world. Likewise, globally minded Wheaton College prepares international missionaries, teachers, pastors and other workers, fulfilling Christ’s Great Commission: “Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you. And behold, I am with you always, to the end of the age” (Matthew 28:19-20).

As Dr. Leon Lederman, the Nobel Prize winning second director of Fermilab, observes, the U.S. Department of Energy research facility investigates with perpetual wonder and perplexity the subatomic conundrums posed by “inner space, outer space, and the time before time.” Exploring multidimensionality from a literary vantage, Wheaton College displays a wardrobe owned by British author C.S. Lewis, which modeled the magical doorway into Narnia. In addition, the Christian liberal arts college archives the papers of Madeleine L’Engle, who wrote A Wrinkle in Time, about a perilous trek through the centuries. In fact, her award-winning science fantasies were inspired by papers published by theoretical physicists Albert Einstein, Max Planck and Niels Bohr.

And despite the efforts of the finest minds and the most sophisticated instrumentality, the comprehensive “theory of everything,” the invisible energy field that holds the universe intact, remains frustratingly elusive. “The universe is the answer,” laments Lederman in The God Particle (1993), “but damned if we know the question.”

If one imagines an anthropomorphized Wilson Hall crying out the plaintive inquiries of a puzzled quantum physicist to the starry cosmos, then Blanchard Hall, standing only ten miles away, simply responds to that plea with Hebrews 1:3, “[Jesus] is the radiance of the glory of God and the exact imprint of his nature, and he upholds the universe by the word of his power.”