On February 8, 2013, Clayton Keenon spoke in the Wheaton College Chapel on the subject of doubt. Twenty years ago, the Wheaton Alumni magazine began a series of articles, titled “On My Mind”, in which Wheaton faculty told about their thinking, their research, or their favorite books and people. Clyde S. Kilby Chair Professor of English Alan Jacobs (who has taught at Wheaton since 1984) was featured in the Summer 1996 issue and also wrote on the same subject of doubt.

——————————

Several years ago I came across a comment by Frederick Buechner that has stuck in my mind: “Doubts are the ants in the pants of faith. They keep it awake and moving.”

Several years ago I came across a comment by Frederick Buechner that has stuck in my mind: “Doubts are the ants in the pants of faith. They keep it awake and moving.”

When I first read those words, I thought–how reassuring! Times of spiritual struggle are a lot easier to get through when you believe that God is working, not just despite them, but through them. And of course, I still believe that God is not only present, but present with special power in every kind of suffering, including the suffering that comes from doubt. The Apostle Paul tells us to “work out [our] salvation in fear and trembling” (Phil. 2:12), which suggests that the attainment of a living faith will be painful.

But I have come to reconsider Buechner’s words. If you were to ask me today what I think about his comment, I would say it all depends on what you mean by “doubt.”

Donald Bloesch has written a book called Faith and Its Counterfeits in which he describes substitutes for genuine Christian faith, for instance, legalism or formalism. Doubt too has its counterfeits–that is, surrogates that lack the integrity and the potential productivity of the real thing. Few spiritual temptations are more dangerous, and more insidiously attractive, than “cheap doubt.”

What is cheap doubt, and how does it differ from productive doubt? In my experiences as a teacher, talking to Christian students in and out of the classroom, I’ve seen both kinds, and I think that I’ve learned to distinguish them.

One day my class on seventeenth-century English literature was considering Sir Thomas Browne, who in his book Religio Medici (“The Faith of a Physician”) considers how doubts may be overcome. Browne’s ideas are strange, but they created an interesting discussion. After a few people had commented, one student raised his hand and asked, “Why would we want to overcome our doubts? If you’re doubting, then you’re thinking; if you’re not doubting, then you’re probably dead, spiritually and intellectually. Surely that’s not what God wants us to be.” At once I remembered Buechner’s words, and I was quick to acknowledge the value of this comment. But I was also a bit bothered, though only later did I figure out why: it was the implication (probably unintentional) that it is appropriate to remain in a state of doubt.

That doubt can be productive doesn’t make it desirable in itself. Doubt can only be useful if we contend against it. Real doubt hurts. Yes, it can spur us to prayer and study of the Scriptures. But there is also a cheap doubt that tends to bring a certain pleasure to its possessor–the pleasure of self-satisfaction, of confident spiritual superiority.

It’s easy to see how tempting this can be. If we see another Christian praying with an intensity and concentration that we cannot match, isn’t there some comfort in believing that she can be so earnest because she has never seriously considered the logical conundrums posed by petitionary prayer to a sovereign God? We doubt, we tell ourselves, because we have thought through these problems, these theological puzzles, and she hasn’t. But if our thinking about these matters leads us to pass confident judgment on the spiritual and intellectual condition of our fellow Christians, we are in real danger.

And even if that earnest prayer warrior is intellectually lazy, it’s not clear that intellectual arrogance is a superior condition, In fact, the doubts in which we take pride may themselves result from laziness–an unwillingness to confront doubts with reflection, Bible study, and prayer. The person who accepts doubts without challenge may be just as lazy as the person who pushes them aside without consideration.

Real doubt will indeed, as Buechner says, keep our faith alive, by forcing us to confront our own frailty. When we cannot, by our own power, silence the inner questioner, then we may be reminded to seek God’s will and to trust in his strength and grace. But if we come to accept our state of doubt, we may be cutting ourselves off from God’s sufficiency.

A Christian liberal arts education does not shy away from tough questions and complex issues; it will therefore always tend to produce doubts. But that makes it all the more imperative that we teachers emphasize also the importance of overcoming doubt and growing in faith. We need to remember the tone of frustration in Jesus’ voice when he tells his disciples of the great things they could do if they had a mustard seed’s portion of faith. We need to remember his astonished joy when the Roman centurion tells him, “You need only say the word and my servant will be cured. Nowhere in Israel have I found such faith” (Mt. 8:8,10). Doubt is part of the road; but it’s not our destination.

—–

The following statement was included at the time of publication:

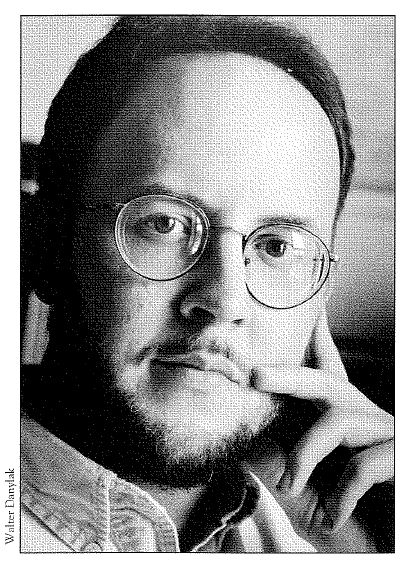

Dr. Alan Jacobs, Associate Professor of English, is a staunch, true Southerner, having received his Ph.D. from the University of Virginia and his B A. from the University of Alabama. He has authored numerous essays and articles for academic and literary journals and magazines, including The American Scholar and First Things. Widely read and listened to, Dr. Jacobs is also a frequent contributor to Mars Hill, an audio cassette literary journal. Currently, he is completing a book on tile poet W. H. Auden, His interests and abilities are diverse, ranging from those of a well-informed scholar, to those of an aspiring basketball star, to those of a restaurant connoisseur. He and his wife, Teri, have one son, Wesley, age 4.