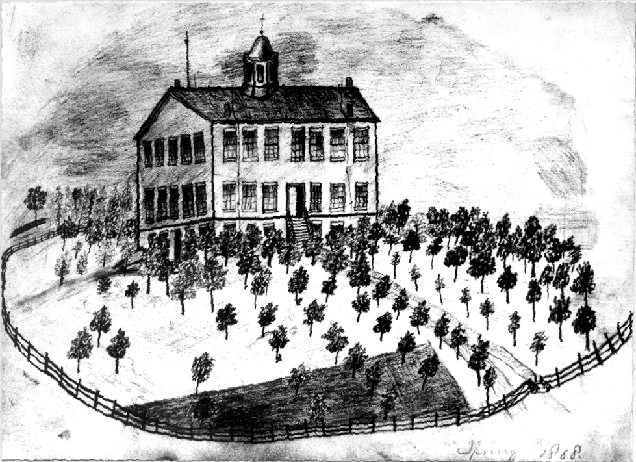

In the early years of Wheaton College, one could say in the early decades, as well, the college relied heavily upon the enrollment of local students. Though it broadly drew students from the region, it was the Wheaton community that served as the “bread and butter” of its tuition dollars.

In the early years of Wheaton College, one could say in the early decades, as well, the college relied heavily upon the enrollment of local students. Though it broadly drew students from the region, it was the Wheaton community that served as the “bread and butter” of its tuition dollars.

In 1860 the transition of leadership from Lucius Matlack to Jonathan Blanchard, from the full control of Wesleyan Methodists to the inclusion of Congregationalists, brought new energy and resources. It also brought a different perspective. For over one hundred years a member of the Wheaton College community could not be a member of a secret oath-bound society. Of any sort. The Illinois Institute and, afterward, Wheaton College were founded on several principles: abolition, temperance and anti-secretism. It was these last two, in tension, that brought forth Wheaton College’s encounter with the Illinois legal system.

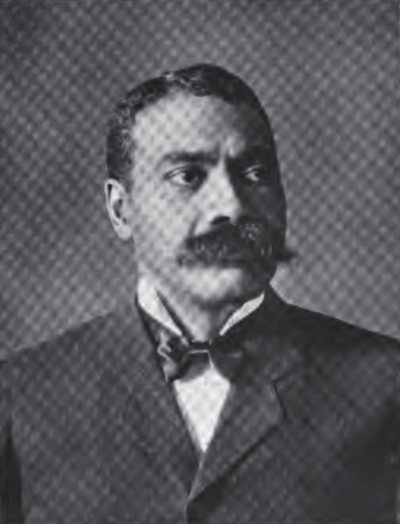

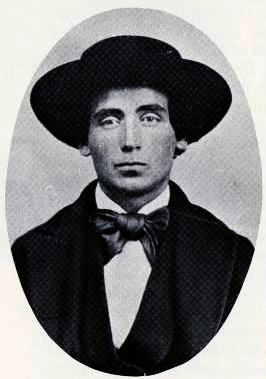

Edwin Hartley Pratt (1849-1930), a local student, was enrolled in the Academic program at Wheaton. He and several other students joined a local Good Templar’s lodge. Known officially as the Independent Order of Good Templars, this fraternal organization stood for many of the principles that Wheaton, and Jonathan Blanchard, held dear: equality for men and women, racial non-discrimination and temperance. It’s motto sounded very good and biblical — “Friendship, Hope and Charity.” However, it was still a secret society and Jonathan Blanchard would have none of it (having believed that the slave system was the work of secret societies).

So, the administration of Wheaton College (i.e. Jonathan Blanchard), tossed out Pratt and his co-secretists.

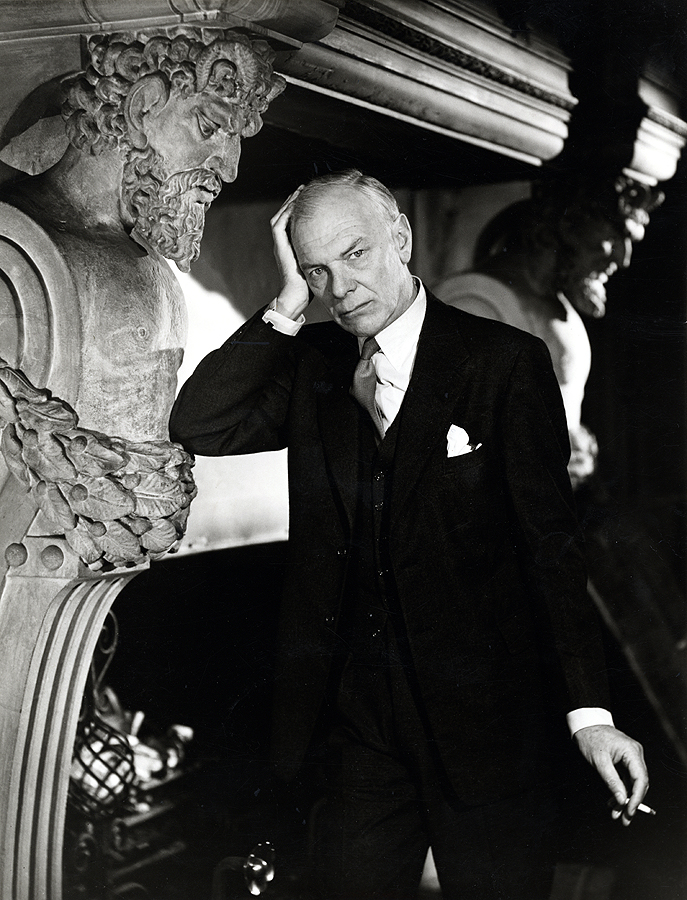

In response Pratt’s father sued Wheaton College under the belief and assumption that his son had done nothing illegal and therefore could not be expelled. A legal battle (Pratt v. Wheaton College) ensued that made its way to the Illinois Supreme Court. In a precedent-setting decision the Illinois Supreme Court upheld the right of Wheaton College, and any other school, to establish rules to govern the lives and discipline of its students, much in the same way that a parent would. As the ruling stated, “A discretionary power has been given, … [and] we have no more authority to interfere than we have to control the domestic discipline of a father in his family.” This firmly established the principle of in loco parentis.

In loco parentis is the legal doctrine that outlines a relationship that is similar to that of a parent to a child. The concept goes back hundreds of years and was embedded in English common-law that was borrowed from by American colonists. The Puritans put this idea to use and it found its way into American elementary and high schools, colleges, and universities. The legal system in the nineteenth century was unwilling to interfere when students brought grievances, particularly in the area of rules, discipline, and expulsion. However, this would change in the 1960s as all forms of authority were challenged.

One may wonder what ever happened to Pratt. After leaving Wheaton, he became a noted homeopathic physician and surgeon in Chicago and was known for his professional writing and work. He wrote Orificial Surgery And Its Application To The Treatment Of Chronic Diseases (1891 and dedicated to his father) and The composite man as comprehended in fourteen anatomical impersonations (1901 and published in several editions). He served as President of the Illinois Homoeopathic Medical Association and served on several medical boards and commissions. In 1877 he married Isadore M. Bailey (a Wheaton student from 1875-1877) with the Rev. C. P. Mercer of the Central Swedenborgen Society officiating. Pratt joined the Chicago Society of the New Jerusalem (Swedenborgian) in 1881.

Oddly enough, Pratt v. Wheaton College wasn’t the only time that Pratt was before the Illinois Supreme Court. In 1903 Pratt was sued for not gaining consent before conducting a hysterectomy on a mentally-ill patient. Pratt lost the case and was fined $3,000. He fought the ruling seeking redress before the Supreme Court. Yet, again, the court failed to rule in his favor.

Poor Pratt.