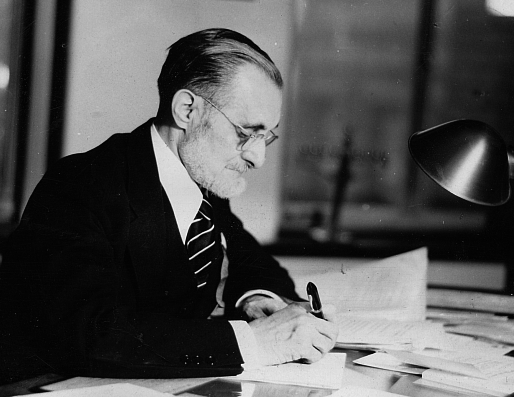

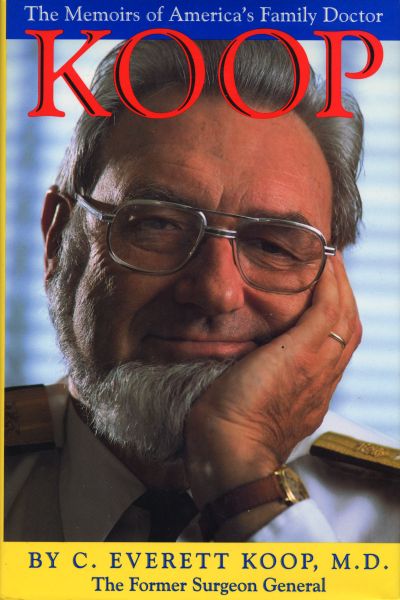

Dr. Charles Everett Koop, former Surgeon General of the United States, died on February 25, 2013, at age 96. Sporting a crisp, double-breasted military uniform, Amish beard and stern aspect, he was an instantly recognizable father-figure during the 1980s, his expert eye continually examining the health trends of the nation. President Ronald Reagan, recognizing Koop’s extraordinary accomplishments in the field of pediatric medicine, appointed him as Surgeon General in 1982. Koop was affiliated with the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

Dr. Charles Everett Koop, former Surgeon General of the United States, died on February 25, 2013, at age 96. Sporting a crisp, double-breasted military uniform, Amish beard and stern aspect, he was an instantly recognizable father-figure during the 1980s, his expert eye continually examining the health trends of the nation. President Ronald Reagan, recognizing Koop’s extraordinary accomplishments in the field of pediatric medicine, appointed him as Surgeon General in 1982. Koop was affiliated with the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia.

An outspoken Christian, Koop relates the circumstances of his 1948 conversion under the ministry of Dr. Donald Grey Barnhouse, pastor of Tenth Presbyterian Church of Philadelphia:

The next Sunday…I finished grand rounds early, and found my feet taking me to Tenth Presbyterian Church, just a few blocks north of the hospital. I entered a back door and quietly slipped up to the balcony. I was just going to observe. I liked what I saw, and I was fascinated by what I heard….I heard teaching from one of the most learned men I ever knew, a true scholar who also possessed a gift of illustrating the complexity – and simplicity – of Christian doctrine by remarkable and incisive stories and similes….I understood that we are all sinners, unable to satisfy God’s standard of righteousness and justice, no matter how hard we try….The preaching from the pulpit made it all clear: that the essence of Christianity was not what we did, but what Christ had done for us. I understood the meaning of the crucifixion, I understood the meaning of Christ’s sacrifice, I understood the meaning of divine forgiveness…Most of all, I understood the love of God….This spiritual awakening had a profound effect on my life and influenced everything that happened thereafter.

Interestingly, Tenth Presbyterian was later pastored by Dr. Philip Ryken, who resigned from its pulpit in 2010 to assume the presidency of Wheaton College, an institution with which Koop enjoyed friendly relations.

As a prominent evangelical engaged in societal issues, Koop, staunchly pro-life, was invited to deliver the address for the 1973 Wheaton College Commencement, during which his daughter, Betsy, graduated. He warned his audience about the disastrous consequences of Roe vs. Wade, predicting that laws will be ridiculous. Soon, he said, teens requiring permission for ear piercing would not need permission for abortions, which will become increasingly common. Also, this legislation will accelerate moral laxity; of course, unknown at the time, it paved the way for the onslaught of AIDS in the 1980s.

Returning to Edman Chapel at Wheaton College for a public forum in 1990, Koop spoke on “Ethical Issues Arising from the AIDS Epidemic.” Discussing challenges and opportunities, he asked, “What better evangelical target than the sick, the homeless, the abandoned and the despised?” As always, he advocated abstinence and monogamy. Throughout the 1990s Koop occasionally appeared on the Wheaton campus, usually in conjunction with events sponsored by the Center for Applied Christian Ethics (CACE).

During a 1989 interview, Christianity Today asked Koop about his famous beard. He replied: “…I grew the beard as a lark when I went with my son Norman to Israel for two weeks. The night before we came home he shaved off his beard and kept his moustache; I shaved off my moustache and kept my beard. We did it just to shock our families. A few days later, when I looked at a picture of myself taken…before I started growing a beard, I realized I had three chins! And I didn’t have them with a beard.”

In 2002 he visited campus for “An Evening with C. Everett Koop,” conducted by Wendy Murray Zoba, heard here.

The papers of Dr. C. Everett Koop (SC-58), comprising manuscripts and correspondence, are housed at Wheaton College Special Collections, available to researchers.

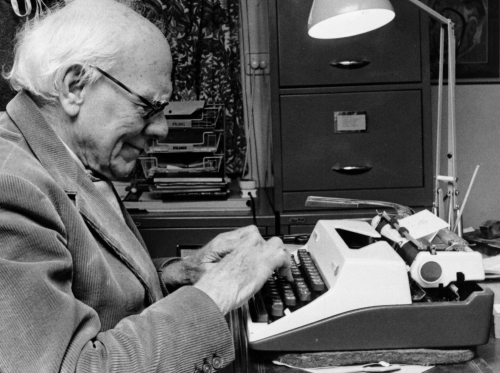

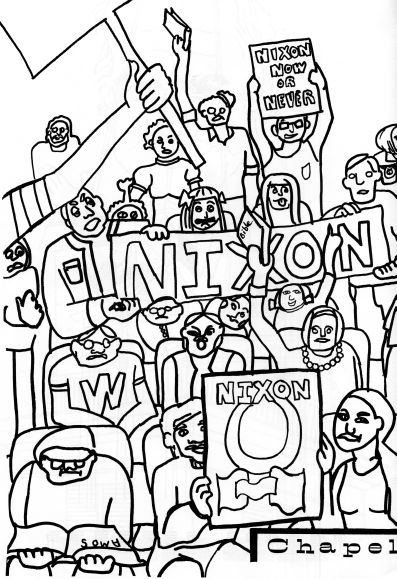

The event was initially suggested by McGovern’s staff, asking for a venue in which he might engage Evangelicals. Activist Jim Wallis, attending Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, was asked to organize the senator’s visit, arranging a breakfast with prominent Christian leaders, in addition to an engagement at Wheaton College. “Actually,” writes Wallis, “the Wheaton Student Council, which issued the invitations to both candidates, accidentally switched the letters, sending Nixon’s by mistake to McGovern.” However, only McGovern accepted. A quiet man raised in a devout Methodist family, McGovern soon found himself in the pulpit of Edman Chapel, standing before an atypically divided house. A few supportive students cheered his unpopular anti-Vietnam War position, but many more booed, waving pro-Nixon banners.

The event was initially suggested by McGovern’s staff, asking for a venue in which he might engage Evangelicals. Activist Jim Wallis, attending Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, was asked to organize the senator’s visit, arranging a breakfast with prominent Christian leaders, in addition to an engagement at Wheaton College. “Actually,” writes Wallis, “the Wheaton Student Council, which issued the invitations to both candidates, accidentally switched the letters, sending Nixon’s by mistake to McGovern.” However, only McGovern accepted. A quiet man raised in a devout Methodist family, McGovern soon found himself in the pulpit of Edman Chapel, standing before an atypically divided house. A few supportive students cheered his unpopular anti-Vietnam War position, but many more booed, waving pro-Nixon banners.

Wallis also remembers:

Wallis also remembers: