Standing before her classroom of Wheaton College students, Dr. E. Beatrice Batson often recited con brio the exquisite verse of Donne, Herbert, Crashaw, Homer, Dante and particularly Shakespeare. A gracious Southern lady, she exhibited both an unaffected dignity and an unassuming humility.

During the years of her retirement, she would reflect on her nine decades, her wide reading and extensive travel. I visited Miss Bea every other week or so at her retirement facility, where she shared her own stories rather than those of her beloved poets. Entering her room, I would boom, “Hey, what’s going on in here?” Seated in her recliner while breathing with difficulty into a respirator, a red blanket tucked beneath her chin for warmth, she beckoned me to sit. As we chatted, she retrieved the chapters of her ripe life from shelves laden with memory.

She remembered when Dr. V. Raymond Edman, fourth President of Wheaton College, occasionally tasked her with editing his devotional books. She would delicately dodge the gig whenever possible to avoid hurting his feelings because she did not like his flowery, mystical style of writing.

On another occasion, when I asked her for a character reference for my registration as an online student at Bob Jones University, Dr. Bea confided that she, too, had attended Bob Jones College, then located in Cleveland, Tennessee, way back in 1938. For how long? “For ten days,” she replied in her deliciously cool, dry drawl. She remembered attending a production of Shakespeare’s Richard III, in which the founder’s talented son impressively portrayed the murderous hunchbacked monarch, though for that performance he had forgotten to limp. “Aside from that,” she added, “he sure was good looking.” When she broke the news to Dr. Bob, Sr. that his college was not for her, he objected. “Bea,” he said, “that just don’t make sense. And if it don’t make sense, God must not be in it.” But it made sense. She moved from there to George Peabody College, then Vanderbilt University and Bryan College. God was in it.

Teaching English at Bryan College from 1947-57, she remarked that she “loved that little school,” but endured a few administrative challenges posed by its president, Dr. Theodore Mercer. She was reticent to comment on those years. When opportunity knocked, she departed Bryan College with the highest recommendations, heading north to Wheaton, Illinois.

On another visit she recalled a 1970’s trip to England with Dr. Clyde Kilby, Chair of the English Department at Wheaton College and founder of the Marion E. Wade Center. Dr. Kilby handed her a meatloaf as a gift for the aging widow of Charles Williams, an Inkling along with J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis. Evidently, the characteristically austere Mrs. Williams was “quite pleased” to receive the dish. Why? Dr. Bea shrugged, observing in her drollest intonation, “For pity’s sake, I cannot fathom why a meatloaf would arouse such excitement.” The details behind the meatloaf caper remain a bit sketchy.

In the following months it became increasingly apparent that the vivid colors of her memory were fading. Her focus was loosening. Books stacked on her bedside table, much-loved titles by Dorothy L. Sayers, Walker Percy and P.D. James, remained untouched. One day she matter-of-factly announced that her manuscript on John Bunyan had been accepted by a major university press who would soon publish it with minimal editing. Congratulations! But I knew that her Bunyan book had been published in 1984.

On the afternoon of my final visit she was awake, though faint and sleepy, lying motionless in her recliner beneath the blanket. After briefly chatting, I held her hand, then stood in the doorway. “Goodbye, honey,” she said, her voice brittle with age and illness. “I love you.”

I love you too, Miss Bea.

Three days later, like the hero of The Pilgrim’s Progress, she entered the Celestial City. The red blanket is cast aside. The respirator is unplugged. Beatrice Batson soars and sings in Henry Vaughan’s “great ring of pure and endless light, all calm as it [is] bright,” joining C.S. Lewis, V. Raymond Edman, Clyde and Martha Kilby, Dorothy L. Sayers, Bob Jones, Madeleine L’Engle, George MacDonald, Theodore Mercer, Shakespeare and all the adoring multitude of students, family and friends who’ve preceded her through the golden gate.

Professor Batson (1920-2019), Professor Emerita of English at Wheaton College, served as Chair of the Department of English for thirteen years and taught courses in Shakespeare for thirty-three years. Professor Batson was the author or editor of 14 books, and the author of numerous chapters in compiled works. During her teaching career, she was a frequent lecturer on college and university campuses in the United States and Canada. After her retirement Professor Batson became the coordinator of the Batson Shakespeare Collection in Special Collections, Buswell Library. She developed the collection into a unique resource bringing together the best scholarship on Shakespeare and the Christian tradition.

Like any good soldier, Dr. George “Bud” Williams (1942-2019) performed all assigned tasks with exactitude and energy. He studied at Penn State and was accepted (but did not attend) Yale University. Excelling in gymnastics, he served as Instructor in Physical Education and Coach at West Point Military Academy. He commanded an ROTC battalion, and taught various aspects of health and athletics at Wheaton College, stressing the necessity for nutrition, hygiene and spiritual renewal.

Like any good soldier, Dr. George “Bud” Williams (1942-2019) performed all assigned tasks with exactitude and energy. He studied at Penn State and was accepted (but did not attend) Yale University. Excelling in gymnastics, he served as Instructor in Physical Education and Coach at West Point Military Academy. He commanded an ROTC battalion, and taught various aspects of health and athletics at Wheaton College, stressing the necessity for nutrition, hygiene and spiritual renewal. Bud was committed to the formation of a hardy but sensitive moral character stabilized and nourished by the Spirit of God, and constantly sought resources that would inculcate this principle to his classes, indoors or out. He knew that when the man or woman securely rooted in Christ passed from the scene, a lingering force of integrity, a wide-ranging, life-giving testimony should remain, ever attracting a fallen humanity to the risen Savior.

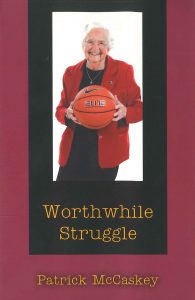

Bud was committed to the formation of a hardy but sensitive moral character stabilized and nourished by the Spirit of God, and constantly sought resources that would inculcate this principle to his classes, indoors or out. He knew that when the man or woman securely rooted in Christ passed from the scene, a lingering force of integrity, a wide-ranging, life-giving testimony should remain, ever attracting a fallen humanity to the risen Savior. Worthwhile Struggle by Patrick McCaskey features a grab bag of inspirational stories woven with tales of exemplary athletes. Included are McCaskey’s “10 Commandments of Football,” based on his upbringing in the Halas-McCaskey family with the Chicago Bears. Deeply involved with faith-based initiatives and charitable causes, McCaskey is active in promoting strong principles and honest gamesmanship.

Worthwhile Struggle by Patrick McCaskey features a grab bag of inspirational stories woven with tales of exemplary athletes. Included are McCaskey’s “10 Commandments of Football,” based on his upbringing in the Halas-McCaskey family with the Chicago Bears. Deeply involved with faith-based initiatives and charitable causes, McCaskey is active in promoting strong principles and honest gamesmanship. Betty Smartt Carter, essayist and novelist, relates her student years at Wheaton College in her poignant, brutally honest memoir, Home is Always the Place You Just Left (2003).

Betty Smartt Carter, essayist and novelist, relates her student years at Wheaton College in her poignant, brutally honest memoir, Home is Always the Place You Just Left (2003).

E.E. Shelhamer (1869-1947), prominent Methodist evangelist and author, writes of his early years at Wheaton College in Sixty Years of Thorns and Roses:

E.E. Shelhamer (1869-1947), prominent Methodist evangelist and author, writes of his early years at Wheaton College in Sixty Years of Thorns and Roses:

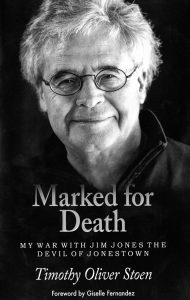

On June 26, 2000, he resumed his career as a California prosecuting attorney. He was nominated in 2010 to the California District Attorneys Association as Prosecutor of the Year, and in 2014 was honored as one of the five top wildlife prosecutors in the state. Stoen tells his remarkable story in Marked for Death: My War with Jim Jones the Devil of Jonestown (2015).

On June 26, 2000, he resumed his career as a California prosecuting attorney. He was nominated in 2010 to the California District Attorneys Association as Prosecutor of the Year, and in 2014 was honored as one of the five top wildlife prosecutors in the state. Stoen tells his remarkable story in Marked for Death: My War with Jim Jones the Devil of Jonestown (2015). Associated primarily with the Viking Press, his deeply ecumenical interests are reflected in the titles of the books he edited: The Portable World Bible (including selections from sacred volumes), The Nature of Religion, The Bible of the World and The Other Jesus: A Narrative Based on Apocryphal Stories Not Included in the Bible. In 1938 he wrote This I Believe: A Letter to My Son, relating his personal faith.

Associated primarily with the Viking Press, his deeply ecumenical interests are reflected in the titles of the books he edited: The Portable World Bible (including selections from sacred volumes), The Nature of Religion, The Bible of the World and The Other Jesus: A Narrative Based on Apocryphal Stories Not Included in the Bible. In 1938 he wrote This I Believe: A Letter to My Son, relating his personal faith. Laity Lodge, situated in the Frio River Valley near Leakey, Texas, overlooks a magnificent vista of forested hills and jagged rock. Far from urban chaos, this retreat stands as a haven for those needing to explore pressing questions, absorb the peace of the Spirit, or simply run into God.

Laity Lodge, situated in the Frio River Valley near Leakey, Texas, overlooks a magnificent vista of forested hills and jagged rock. Far from urban chaos, this retreat stands as a haven for those needing to explore pressing questions, absorb the peace of the Spirit, or simply run into God.

This statement summarizes Muriel’s relentless love of learning. Afflicted with a “spastic” leg ailment in addition to her blindness, Muriel managed to convey a radiant love for people and education. “There is nothing that she will not try or do,” wrote a former grade school teacher, “and she wants no sympathy.”

This statement summarizes Muriel’s relentless love of learning. Afflicted with a “spastic” leg ailment in addition to her blindness, Muriel managed to convey a radiant love for people and education. “There is nothing that she will not try or do,” wrote a former grade school teacher, “and she wants no sympathy.” Presenting himself as a backwoods “bootleg” hayseed, wearing cowboy boots and straw hats, he actually possessed a fine intellect, abundant courage and quick wit. Campbell, siding unhesitatingly with the oppressed and disenfranchised, was one of four who boldly escorted African American students, known as the “Little Rock Nine,” into the racially segregated Little Rock Central High School in 1957. Campbell was also the only white man to attend the founding of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1957.

Presenting himself as a backwoods “bootleg” hayseed, wearing cowboy boots and straw hats, he actually possessed a fine intellect, abundant courage and quick wit. Campbell, siding unhesitatingly with the oppressed and disenfranchised, was one of four who boldly escorted African American students, known as the “Little Rock Nine,” into the racially segregated Little Rock Central High School in 1957. Campbell was also the only white man to attend the founding of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1957.