Betty Smartt Carter, essayist and novelist, relates her student years at Wheaton College in her poignant, brutally honest memoir, Home is Always the Place You Just Left (2003).

Betty Smartt Carter, essayist and novelist, relates her student years at Wheaton College in her poignant, brutally honest memoir, Home is Always the Place You Just Left (2003).

My love for Wheaton is now so great that it’s hard to remember why I disliked it when I first went. But I did. What caused me to choose such a vibrantly Christian college in the first place, I cannot tell, except that my brother Danny had gone there in the early 1970s and had come back making it sound like heaven on earth. Maybe I thought I’d follow a similar path. I’d leave home a lonely and confused teenager and come back a happy, well-rounded adult. As for my Christianity, I’d continue the part of the small-time rebel and cynic, only without having to deceive anyone about it.

Driving north from Georgia with her family, Betty warily embraced the next chapter of her life.

In the fall of 1983, I took my cynical self north to Wheaton College, the very flower of evangelical Christianity. The school had a fine academic reputation, but it was best known for turning out missionaries, evangelists and martyrs, not to mention the odd Republican politician….it allowed no drinking or smoking or dancing (except chaste square-dancing such as had been practiced across the northern Illinois prairie for nigh on one hundred and fifty years); it encouraged Christian dating and marriage but prohibited all forms of hanky-panky. The unofficial motto of the school was “in loco parentis,” which meant that I wasn’t supposed to do anything there to bring shame upon my Mama and Daddy, and if I did, I’d be sent home on the next bus out of Chicago.

Betty was off to a rocky start, struggling with a few personal issues. Touring the campus with her parents, she entered freshman orientation with a decided sense of dis-orientation.

I felt myself slipping into something like shock. Why had I decided to leave behind my home, my family, and above all my beloved friend in order to come to this place that seem like nothing so much as a great big youth group meeting, a church service that would on on for four years?

However, as she developed friendships, along with widening intellectual and spiritual perspectives, she found a surer voice and steadier feet.

Then one day after reading [Augustine’s] Confessions, I sat in chapel and had a sort of epiphany. I looked out to my left and right, in front of me and behind me, over those thousands of serious young faces, and I realized that behind so many of the faces must be minds and hearts, like mine, in turmoil. I’d thought Wheaton evangelicals as hypocrites because they seemed so falsely positioned. But they were being deceitful only in their behavior — not in their hopes, which were real. They honestly did want to be passionate about God. They wanted to be the strong, faithful people that they appeared to be when they prayed aloud at dorm meetings, when they sang, “They joy of the Lord is my strength!”…Instead of resenting them, I felt compassion for them. It was as if a great backdrop had fallen away at the front of the chapel and I saw the inner workings of the place: people worshiping, doubting, praying, turning in all directions, longing for God but unable to wait for God….I left chapel feeling a burden lifted off of me: I didn’t have to agree with these people, or accept all their thinking, in order to sympathize. I could laugh at them for the excesses and love them for their hopes.

Betty Smartt Carter has also published I Read It in the Wordless Book and a mystery novel, The Tower, the Mask and the Grave. Her writing has appeared in Books & Culture and several other journals.

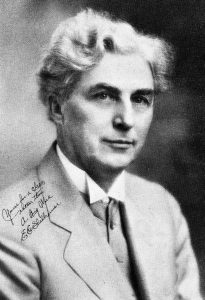

E.E. Shelhamer (1869-1947), prominent Methodist evangelist and author, writes of his early years at Wheaton College in Sixty Years of Thorns and Roses:

E.E. Shelhamer (1869-1947), prominent Methodist evangelist and author, writes of his early years at Wheaton College in Sixty Years of Thorns and Roses:

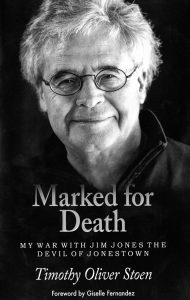

On June 26, 2000, he resumed his career as a California prosecuting attorney. He was nominated in 2010 to the California District Attorneys Association as Prosecutor of the Year, and in 2014 was honored as one of the five top wildlife prosecutors in the state. Stoen tells his remarkable story in Marked for Death: My War with Jim Jones the Devil of Jonestown (2015).

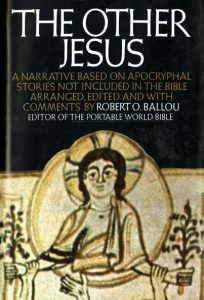

On June 26, 2000, he resumed his career as a California prosecuting attorney. He was nominated in 2010 to the California District Attorneys Association as Prosecutor of the Year, and in 2014 was honored as one of the five top wildlife prosecutors in the state. Stoen tells his remarkable story in Marked for Death: My War with Jim Jones the Devil of Jonestown (2015). Associated primarily with the Viking Press, his deeply ecumenical interests are reflected in the titles of the books he edited: The Portable World Bible (including selections from sacred volumes), The Nature of Religion, The Bible of the World and The Other Jesus: A Narrative Based on Apocryphal Stories Not Included in the Bible. In 1938 he wrote This I Believe: A Letter to My Son, relating his personal faith.

Associated primarily with the Viking Press, his deeply ecumenical interests are reflected in the titles of the books he edited: The Portable World Bible (including selections from sacred volumes), The Nature of Religion, The Bible of the World and The Other Jesus: A Narrative Based on Apocryphal Stories Not Included in the Bible. In 1938 he wrote This I Believe: A Letter to My Son, relating his personal faith. Laity Lodge, situated in the Frio River Valley near Leakey, Texas, overlooks a magnificent vista of forested hills and jagged rock. Far from urban chaos, this retreat stands as a haven for those needing to explore pressing questions, absorb the peace of the Spirit, or simply run into God.

Laity Lodge, situated in the Frio River Valley near Leakey, Texas, overlooks a magnificent vista of forested hills and jagged rock. Far from urban chaos, this retreat stands as a haven for those needing to explore pressing questions, absorb the peace of the Spirit, or simply run into God.

Compiled by Douglas J. Douma and edited by Thomas W. Juodatis, Clark and His Correspondents: Selected Letters of Gordon H. Clark (2017) presents an array of Clark’s exchanges with such prominent evangelical and fundamentalist leaders as J. Oliver Buswell, V. Raymond Edman, E.J. Carnell, Cornelius Van Til, Carl F.H. Henry and J. Gresham Machen. The compilation uses many letters scanned from the College Archives of Buswell Library.

Compiled by Douglas J. Douma and edited by Thomas W. Juodatis, Clark and His Correspondents: Selected Letters of Gordon H. Clark (2017) presents an array of Clark’s exchanges with such prominent evangelical and fundamentalist leaders as J. Oliver Buswell, V. Raymond Edman, E.J. Carnell, Cornelius Van Til, Carl F.H. Henry and J. Gresham Machen. The compilation uses many letters scanned from the College Archives of Buswell Library.