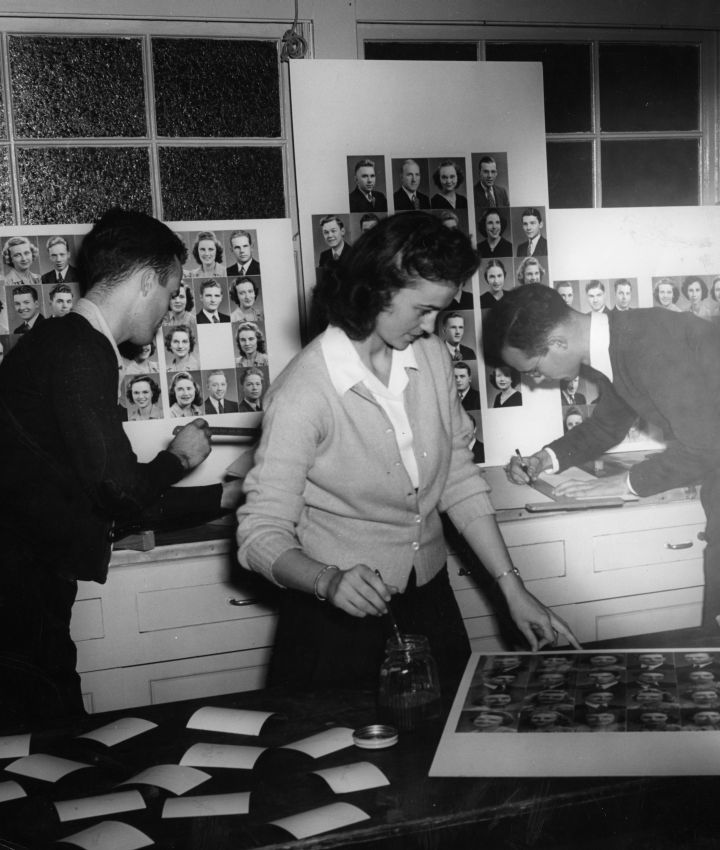

2016 marks the final year in which the hard copy of Wheaton College yearbook, The Tower, is published. Due to budgetary restraints and relative lack of interest among students, the administration decided to cease publication. From this point forward information will be collected digitally. Collectively, the yearbooks cover approximately 2/3 of the college’s 156-year life, capturing for posterity priceless moments and pertinent personal information.

2016 marks the final year in which the hard copy of Wheaton College yearbook, The Tower, is published. Due to budgetary restraints and relative lack of interest among students, the administration decided to cease publication. From this point forward information will be collected digitally. Collectively, the yearbooks cover approximately 2/3 of the college’s 156-year life, capturing for posterity priceless moments and pertinent personal information.

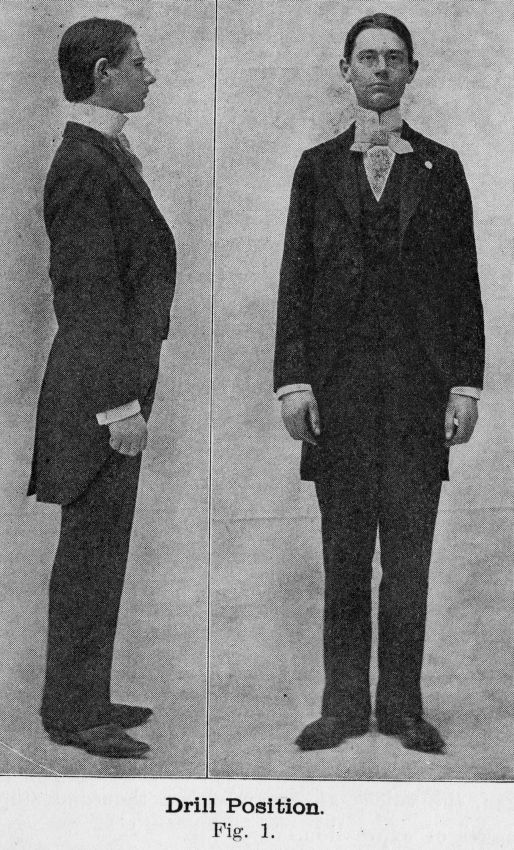

It was 30 years after the college’s founding in 1860 before students published the first iteration of the yearbook, Wheaton College Echoes, ’93. An editorial excitedly anticipates a bright future, observing with comic pomposity, “And then, don’t you know, exuberant genius is best developed by at least an annual overflow.” The editors wistfully quote:

That I for dear auld Wheaton’s sake,

Some useful plan or book could make,

Or sing a song at least?

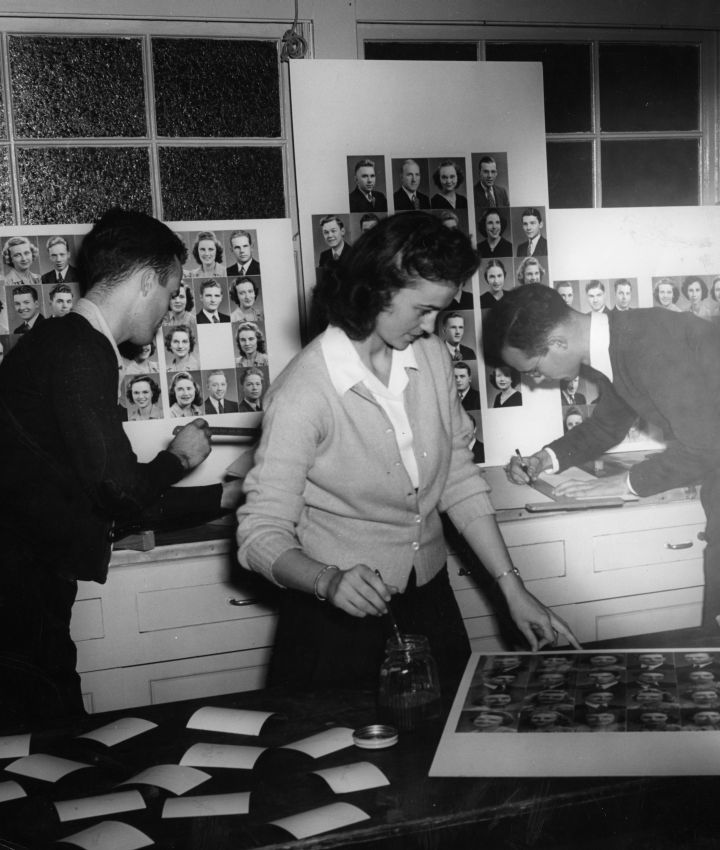

Echoes, publishing advertisements, student and faculty directories and silly anecdotes, continued until 1900 when it ceased publication for reasons now forgotten. After a lengthy absence the yearbook resurfaced in 1922 as The Tower, adopting the traditional format of profiling students of each class and faculty through photos and chatty text, along with chapters dedicated to sports, music, literary societies and various clubs. The editors write:

In presenting the first edition of The Tower, the Junior Class has attempted to concentrate the events of the college year in such form that they will be kept and treasured by the students in years to come….If this book affords the graduate pleasant reminiscences and inspires the undergraduate with a greater devotion to Alma Mater, the Juniors will feel they have accomplished their plan.

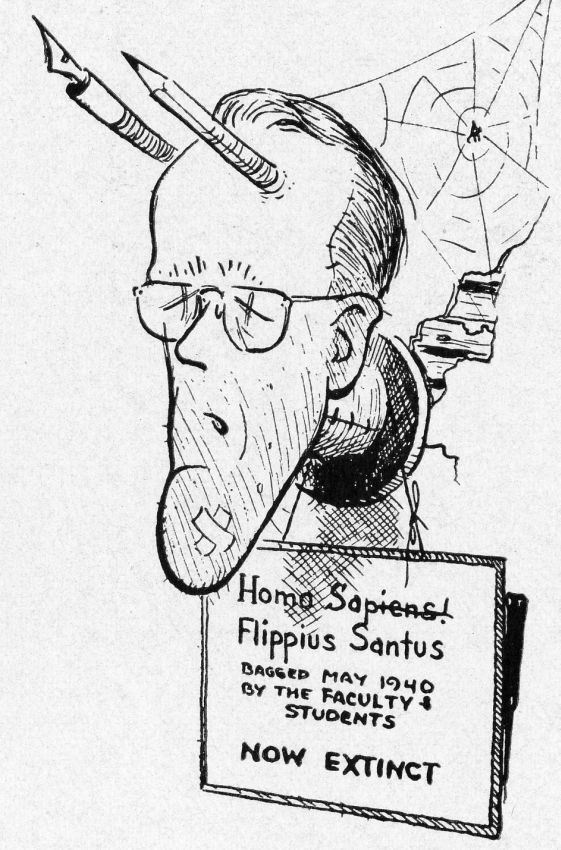

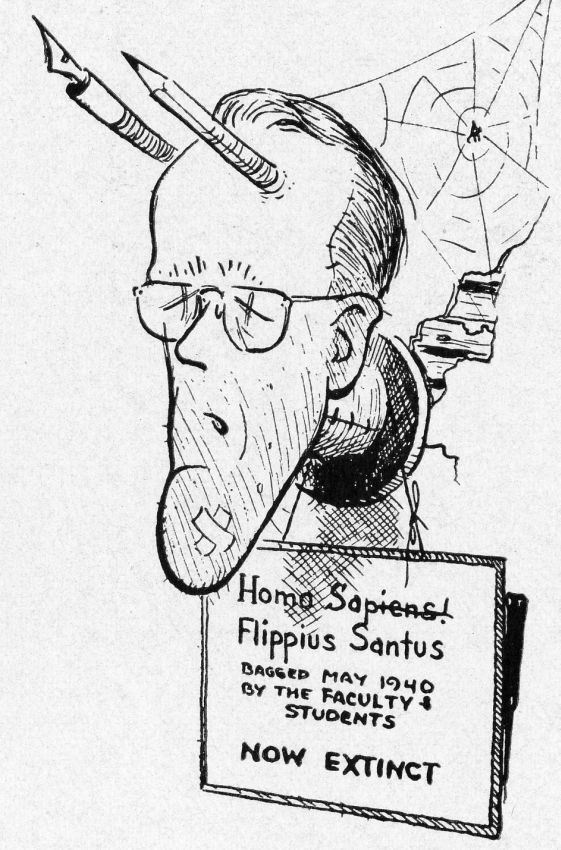

Indeed, The Tower, initially printed by Schulkins Printing Co. of Chicago, appeared annually, maintaining traditional packaging with a few notable variations. For instance, the 1941 Tower, edited by artist Phil Saint, is liberally peppered with his own gently humorous caricatures of faculty and campus life. In fact, Saint includes on the final page a cartoon of himself as a stuffed head, Flippius Santus, “now extinct.”  Years later Saint’s brother, Nate, would die with Jim Elliott and four other missionaries at the hands of Waorani tribesmen in Ecuador.

Years later Saint’s brother, Nate, would die with Jim Elliott and four other missionaries at the hands of Waorani tribesmen in Ecuador.

In 1945 a saddle-stitched paperback supplement, The Armed Forces Tower, exhibiting several galleries of Wheaton College active duty soldiers and deceased Gold Star Veterans, was distributed with The Tower. The Armed Forces Tower also exhibits an illustration for the proposed Memorial Student Building, eventually built in 1950 after a fundraising campaign. The structure now serves as the political science department. The supplemental edition also contains Dr. V. Raymond Edman’s famous tribute to the young men and women populating his beloved campus, the “brave sons and daughters true” who carry the gospel of Christ to far countries.

The most innovative packaging of The Tower appeared in 1972, when it was divided into three paperbacks, each profiling an aspect of campus life with artistic photos and scattered poetry. The package includes a cassette tape recording of philosophy professor Dr. Stuart Hackett’s band in concert.

Like any journal, The Tower faithfully records the moods, milestones and fancies of the hour. The College Archives, Buswell Library, where a complete set of The Tower is maintained, bids a fond adieu to this perennially useful historical document.

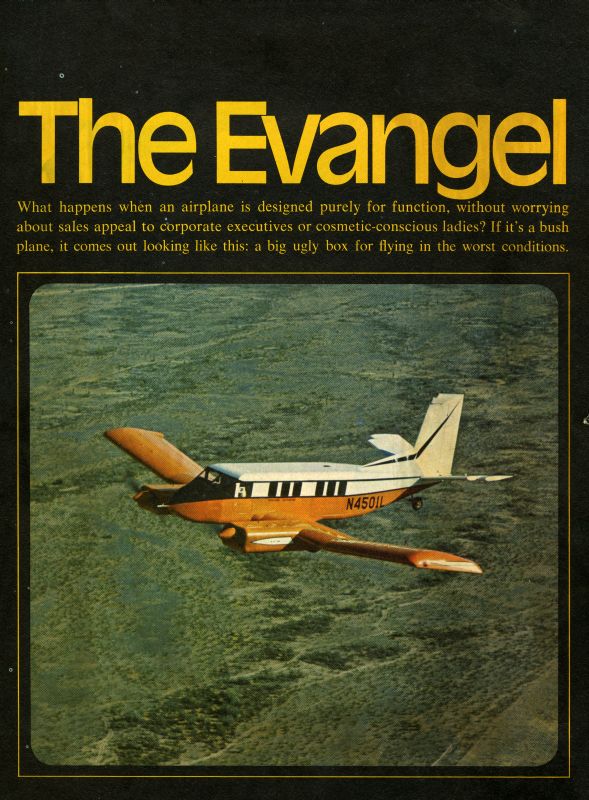

Receiving funding from several Chicago laymen, the Evangel 4500 was ready for its first major mission in 1969. Passengers for thetwo-month voyage to South America were pilot Mortenson, Dr. Paul Wright, chairman of the chemistry department at Wheaton College, and nine other board members of Project Evangel.

Receiving funding from several Chicago laymen, the Evangel 4500 was ready for its first major mission in 1969. Passengers for thetwo-month voyage to South America were pilot Mortenson, Dr. Paul Wright, chairman of the chemistry department at Wheaton College, and nine other board members of Project Evangel. 2016 marks the final year in which the hard copy of Wheaton College yearbook, The Tower, is published. Due to budgetary restraints and relative lack of interest among students, the administration decided to cease publication. From this point forward information will be collected digitally. Collectively, the yearbooks cover approximately 2/3 of the college’s 156-year life, capturing for posterity priceless moments and pertinent personal information.

2016 marks the final year in which the hard copy of Wheaton College yearbook, The Tower, is published. Due to budgetary restraints and relative lack of interest among students, the administration decided to cease publication. From this point forward information will be collected digitally. Collectively, the yearbooks cover approximately 2/3 of the college’s 156-year life, capturing for posterity priceless moments and pertinent personal information. Years later Saint’s brother, Nate, would die with Jim Elliott and four other missionaries at the hands of Waorani tribesmen in Ecuador.

Years later Saint’s brother, Nate, would die with Jim Elliott and four other missionaries at the hands of Waorani tribesmen in Ecuador.