The details of James Burr’s early life are little-unknown. It appears from the scant evidence that he was born in Cuba, New York, in 1814, but details of the subsequent twenty years trail off, until his enrollment at Oberlin College in 1834-35. He stayed a year and then was drawn away to The Mission Institute, also known as The Adelphia Theopolis Mission Institute, in Quincy, Illinois. The Institute was founded by Dr. David Nelson, a former Revolutionary War soldier and physician. Both Oberlin and The Institute were renowned for their open sympathies with the cause of abolition.

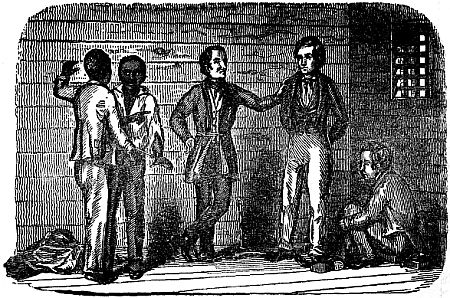

After a reconnaissance mission into Missouri to free those enslaved, on the night of July 12th, 1841 Burr returned with two classmates, George Thompson and Alanson Work, and the slave owners ambushed them during their rescue attempt. The men were bound by ropes and paraded off to Palmyra, Missouri. They were quickly indicted for stealing slaves, held without bail, and chained together for months until their trial was called. In 1841 Missouri had no law against encouraging slaves to flee north. In addition, the testimony of blacks could not be used in court as evidence against a white man. Technically the three had broken no law since no slave had run away. In addition, they had spoken only to slaves and there was no legally admissible evidence for the prosecution. Still, the men were tried in mid-September on an illogical combination of trumped-up charges and found guilty of grand larceny though they had stolen nothing. Outside the court, the town’s citizens prepared a gallows “in case they were acquitted.” Dubbed “The Quincy Abolitionists,” they each received 12 years at hard labor in the state penitentiary, and, still in chains, they left for Jefferson City. Years later George Thompson wrote his memoir Prison Life and Reflections from the prison journals and letters from all three men . Thompson vividly recalled their first night together in jail, “[we] knelt down, and committed ourselves to God, imploring His guidance and protection, feeling that He had wise purposes to accomplish by this unintelligible dispensation.” Denied paper for nearly two years, Thompson kept his journal on “bedstead, old boards, and blank leaves, by recording, sometimes a word, sometimes two or three words, and sometimes a sentence or two-just enough to bring the occurrence or scene to my mind-with the date.” Deprived of all but the thinnest of clothing and blankets, they almost froze during the first two winters.

. Thompson vividly recalled their first night together in jail, “[we] knelt down, and committed ourselves to God, imploring His guidance and protection, feeling that He had wise purposes to accomplish by this unintelligible dispensation.” Denied paper for nearly two years, Thompson kept his journal on “bedstead, old boards, and blank leaves, by recording, sometimes a word, sometimes two or three words, and sometimes a sentence or two-just enough to bring the occurrence or scene to my mind-with the date.” Deprived of all but the thinnest of clothing and blankets, they almost froze during the first two winters.

Eventually James was permitted to refashion their two small beds into one so that all three could sleep together and “we could take turns getting into the middle. If an outside one was becoming frostbitten, he only had to request the middle one to exchange places awhile; and we were ever ready to oblige and accommodate for each knew how to sympathize with the other. So far from murmuring, we had great cause for thankfulness-for many were in a worse condition than we.” As “the cause” advanced, the health of all three declined, but Burr was most severely affected, and he was often unable to work for weeks at a time.

On January 19, 1844, James’s arm was caught in a machine, twisted and crushed in such a way that both bones in the wrist were broken with one protruding through the skin. The doctor “set it according to the best of his skill; which we feared at the time was not very good, as the result proved. He [James] bore the setting very well, scarcely uttering a groan-painful yet needful. As feared, his arm never healed properly, remaining useless for the remainder of his life. Burr was repeatedly ill and unemployed but this probably worked to his advantage. Inasmuch as he was of little value to the prison lessees, he was pardoned a year later. Freed quite suddenly in January 1846, he remembered feeling so stricken at the thought of leaving George alone that he offered to give his pardon to his Brother Thompson, but the authorities wouldn’t permit it. Burr returned to Quincy after his pardon, but moved about one hundred miles north to Princeton, Illinois, by 1849. The 1850 census reported him working as a carpenter and having a wife, Mary Anne Munroe, and two children: Charles H. and Mary A. Munroe who were 13 and 11 years of age respectively.

On January 19, 1844, James’s arm was caught in a machine, twisted and crushed in such a way that both bones in the wrist were broken with one protruding through the skin. The doctor “set it according to the best of his skill; which we feared at the time was not very good, as the result proved. He [James] bore the setting very well, scarcely uttering a groan-painful yet needful. As feared, his arm never healed properly, remaining useless for the remainder of his life. Burr was repeatedly ill and unemployed but this probably worked to his advantage. Inasmuch as he was of little value to the prison lessees, he was pardoned a year later. Freed quite suddenly in January 1846, he remembered feeling so stricken at the thought of leaving George alone that he offered to give his pardon to his Brother Thompson, but the authorities wouldn’t permit it. Burr returned to Quincy after his pardon, but moved about one hundred miles north to Princeton, Illinois, by 1849. The 1850 census reported him working as a carpenter and having a wife, Mary Anne Munroe, and two children: Charles H. and Mary A. Munroe who were 13 and 11 years of age respectively.

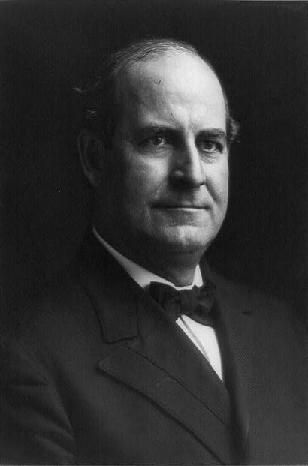

The Illinois Institute had been founded in 1853 by Wesleyan Methodists who had split from the main body of the Methodist Church over the question of slavery. Early in 1859, two months before his death from consumption, which he probably contracted while in prison, he prepared a will leaving $300 of his $4000 estate to the Illinois Institute in Wheaton. This money was “to be used for the educating of indigent fatherless young men who were wholly devoted to the cause of Christ wishing a preparation for such a calling and wishing to preach said gospel to all irrespective of color and who are opposed to slavery and sin of every grade and in favor of the reformers of the present day.” The question of how Burr’s grave came to campus remains an unsolved mystery. According to a brief letter in the Christian Cynosure of February 20, 1879, by George Thompson, Burr was buried there “by special request.” He wished his grave to be on grounds untrampled by slavery. There were many other ties between the tiny school and the city where Burr lived. In 1860 two of the trustees of the institution, Rufus Lumry and Owen Lovejoy, (another zealous abolitionist), list Princeton, Illinois, as their home address. In addition, John Cross, who taught in the school, was also from Princeton. Undoubtedly, Burr was well acquainted with the sympathies of these men and knew of their efforts to aid runaway slaves. Given tuition costs of $24 per year for the college by 1860, his legacy endowed a full scholarship. When forced to reorganize in 1859-60, the administration natu rally looked for a man who felt as deeply as they did about the issue of abolition. Consequently, they invited Jonathan Blanchard to become the president of the struggling school and he arrived in January, 1860, almost a year after Burr’s burial. No one knows whether these two men were acquainted, but it is almost certain that they knew of each other and their joint sympathy for the abolitionist cause.

rally looked for a man who felt as deeply as they did about the issue of abolition. Consequently, they invited Jonathan Blanchard to become the president of the struggling school and he arrived in January, 1860, almost a year after Burr’s burial. No one knows whether these two men were acquainted, but it is almost certain that they knew of each other and their joint sympathy for the abolitionist cause.

For years Burr rested quietly, his grave officially decorated once each year by students. Then the damage done by pranksters to the tombstone caused campus officials to remove the seven-foot high marker and replace it with one flush with the ground. In April of 1959, there was a special commemorative service in his memory, focusing attention on his life. Although speculation about Burr waxed and waned following that occasion, he didn’t return to prominence until 1987 when the new James E. Burr Scholarship for first-year minority students was announced.