This past year, Buswell Library Special Collections had the privilege of having Wheaton College senior Jenna Watson help us process some significant donations we received in the last few years. One such donation was from Marilyn Unruh, a dear friend of author Madeleine L’Engle. Jenna writes a reflection on what she found below:

Buswell Library Special Collections recently received a donation of correspondence from author Madeleine L’Engle to one of her dearest friends, Marilyn Unruh. This correspondence spans nearly thirty years (1972-2000) and paints a portrait of a deep, unbreakable friendship. These letters feature everything we would expect from Madeleine: creative theological reflection, affirmation of love as the strongest force in the world, and unwavering belief in the power of story as a vehicle for truth. They affirm that the Madeleine who wrote A Wrinkle in Time, Walking on Water, and Meet the Austins is her true self. However, this correspondence reveals that Madeleine depended greatly on those around her for inspiration and correction. Her friend Marilyn’s challenges to Madeleine’s theology shaped the contours of Madeleine’s books we read today. This makes an understanding of Madeleine and Marilyn’s friendship essential to anyone who seeks to truly know Madeleine.

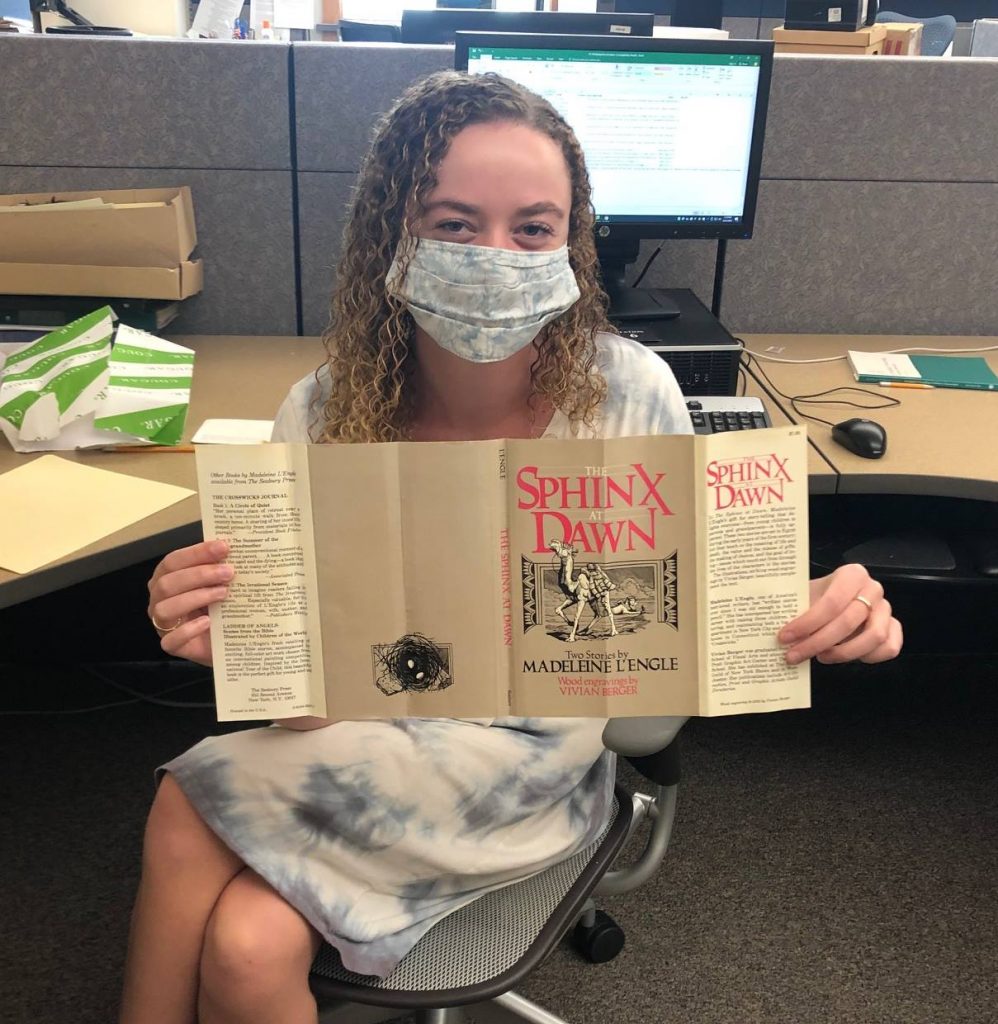

Jenna Watson with book cover Madeleine L’Engle used to write Marilyn Unruh

The clearest example of Marilyn challenging Madeleine’s theology is in their correspondence about Bright Evening Star, a nonfiction book reflecting on the mystery of the incarnation. On September 16, 1996, Marilyn wrote Madeleine with her impressions after reading an early draft of Bright Evening Star:

Essentially, I saw your premise as being that Jesus had a dual nature, divine and human, and that he elected to stay within the limits of the human throughout. He refused to do “godness” things, “godness” meaning performing supernatural acts of power, the spectacular, the sensational, but chose rather to stay human in order to show us how to be human.

Based on this, I doubt that the Jesus you are presenting here is a person I would be able to trust with my life and be willing to follow heart and soul. I will try to articulate what I found confusing about your manuscript.

Marilyn then articulates three problems she sees with Madeleine’s Christology. First, she writes that Madeleine’s explanation of Christ’s ability to perform supernatural acts of power is incompatible with the image of God as total love. Second, this Christology does not allow Marilyn to relate to Christ because his options are different from human options. Third, this Christology does not teach Marilyn how to be more human.

“In short,” Marilyn writes, “I need a Jesus who brought his god-nature, (not a god-nature perceived by our finite minds as supernatural power, but god-nature as divine total all-encompassing love) into my human dual (good and evil nature)…Show me this Jesus in your manuscript and I will gladly love and serve him.”

Madeleine’s response, characteristically scrawled on the back of a book cover she wanted to show Marilyn, said: “Many thanks for the thoughtful letter. What you asked me to do was what I was trying to do! But I think the problem was that I was trying too hard to prove points and so forgot the winsome lovableness of the human Jesus! I have already put a new disc in the machine and started again.”

Marilyn replied with further encouragement and exhortation. “People listen to you, Madeleine, so it’s terribly important that you not sell them short. I’m relieved that you are willing to work at revision. You don’t have to be didactic. You don’t have to take a position and argue your point. Just show clearly where Jesus will lead us if we follow him.”

In addition to a more robust understanding of Madeleine’s theology, this collection is a strong testament to the power of Christian friendship that affirms, challenges, and unconditionally loves. Marilyn’s loving Christian exhortation and Madeleine’s grateful acceptance of it suggests that their friendship truly was as unconditional as they frequently assert. As Madeleine writes to Marilyn in June 1992, “We make a terrific combination, and I think together we do the Lord’s work in a stronger way than either of us does singly.” (June 1992, Item 2, Folder 16, Box 6, SC-03).

An advertisement for power tools might feature burly men in a noisy workshop. An ad for luxurious perfume might feature sultry film actresses or pop divas posing in exotic locales. But what if the product is an annuity contract? Naturally, the advertisement will display a kindly-visaged matron in her rocking chair, serenely contemplating her sunset days.

An advertisement for power tools might feature burly men in a noisy workshop. An ad for luxurious perfume might feature sultry film actresses or pop divas posing in exotic locales. But what if the product is an annuity contract? Naturally, the advertisement will display a kindly-visaged matron in her rocking chair, serenely contemplating her sunset days.