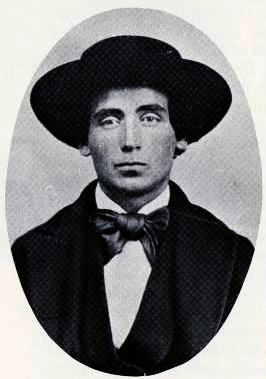

When Lyman Stewart was a young man he wanted to become a missionary. However the discovery of oil in his native Pennsylvania would forever change the course of his life, but not the influence of his faith. When oil was found in the rolling Allegheny mountains near Titusville, Stewart attempted to risk his $125 in missionary funds in the hopes of maximizing his return. His first two attempts were a bust and Stewart had to return to work with his father in the tanning business. Stewart’s efforts were interrupted by the Civil War, where he enlisted in the 16th Pennsylvania Cavalry.

When Lyman Stewart was a young man he wanted to become a missionary. However the discovery of oil in his native Pennsylvania would forever change the course of his life, but not the influence of his faith. When oil was found in the rolling Allegheny mountains near Titusville, Stewart attempted to risk his $125 in missionary funds in the hopes of maximizing his return. His first two attempts were a bust and Stewart had to return to work with his father in the tanning business. Stewart’s efforts were interrupted by the Civil War, where he enlisted in the 16th Pennsylvania Cavalry.

Upon mustering out of the army Stewart put his hand back to the drill in search of oil. Still unsuccessful in Pennsylvania Stewart sold his oil interests to John D. Rockefeller and moved to California joining forces with Wallace Hardison. In California Stewart’s missionary dreams were capped when he struck oil. By 1886 15% of all oil production came from Hardison and Stewart. In 1890 they merged their work with Thomas Bard and Paul Calonico to form Union Oil Company, now known as Unocal.

Though Stewart never went into the fields as a Christian worker his influence was known and felt. One of the early oil fields in California was known as Christian Hill due to Stewart’s influence and moral strictness. Stewart worked hard to provide for several institutions who prepared laborers for the field. Stewart was a philanthropist and in 1908 was co-founder with T. C. Horton of the Bible Institute of Los Angeles (now known as Biola University). Stewart also helped found the Pacific Gospel Mission (now the Union Rescue Mission) in 1891.

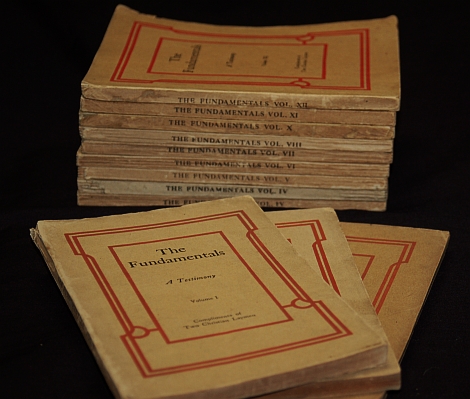

He and his brother Milton also anonymously funded The Fundamentals, a twelve-volume publication that became a classic defense of the Christian faith and was the foundation of the fundamentalist Christian movement. The Fundamentals: A Testimony To The Truth were edited by A. C. Dixon and later by R. A. (Reuben Archer) Torrey as a set of 90 essays in 12 volumes published to affirm orthodox Protestant beliefs and defend against encroaching liberalism. Authors included noted theologians and clergy from a wide-range of theological traditions: B. B. Warfield, C. I. Scofield, G. Campbell Morgan, Bishop Ryle, R. A. Torrey, H. C. G. Moule, James Orr, and others.

He and his brother Milton also anonymously funded The Fundamentals, a twelve-volume publication that became a classic defense of the Christian faith and was the foundation of the fundamentalist Christian movement. The Fundamentals: A Testimony To The Truth were edited by A. C. Dixon and later by R. A. (Reuben Archer) Torrey as a set of 90 essays in 12 volumes published to affirm orthodox Protestant beliefs and defend against encroaching liberalism. Authors included noted theologians and clergy from a wide-range of theological traditions: B. B. Warfield, C. I. Scofield, G. Campbell Morgan, Bishop Ryle, R. A. Torrey, H. C. G. Moule, James Orr, and others.

The name of the series were foundational to a religious counter-movement that spawned the movement’s name — Fundamentalism. A Fundamentalist was one who ascribed to the theological perspective espoused in its pages. Attacking higher criticism, socialism, evolution and many other “isms.” They set out what was believed to be the fundamentals of Christian faith, this series were to be sent free to hundreds of thousands of ministers, missionaries, Sunday School superintendents and others active in Christian ministry.

Stewart’s legacy for conservative Christianity was much greater as the benefactor of Biola and the Fundamentals, though one wonders what the results would have been if he’d not been a prodigal with his missionary savings.