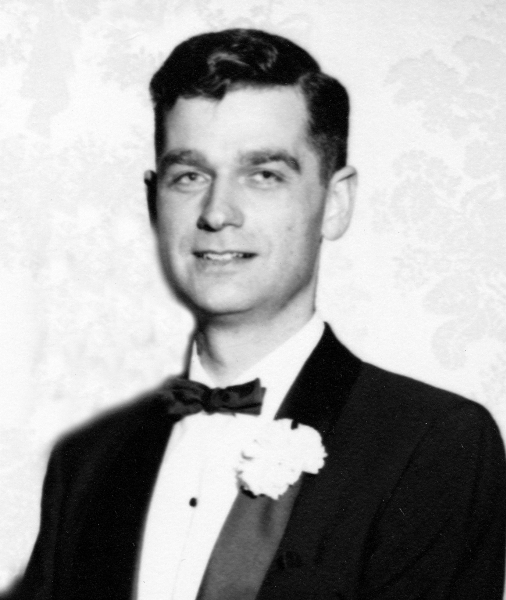

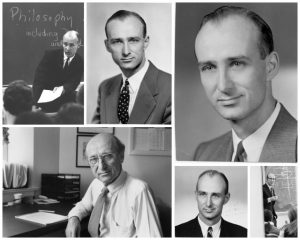

Twenty years ago, the Wheaton Alumni magazine featured a series of articles in which Wheaton faculty told about their thinking, their research, or their favorite books and people. Distinguished Professor of Philosophy Emeritus Arthur F. Holmes (who taught at Wheaton from 1951-1994) began the series in the January 1991 issue.

When Wheaton Alumni asked me to tell alumni what I am thinking about nowadays, my mind turned to a recent best-seller that both Christian college and public university educators have been talking about for the last three or four years. Alan Bloom complains in The Closing of the American Mind that today’s students talk as if no such things as right or wrong exist; he adds that they have no world-view in which any such values might be grounded, and that as a result they lack a strong sense of personal identity. Instead we hear talk of “alternative lifestyles,” as if morality is simply a matter of personal preferences.

When Wheaton Alumni asked me to tell alumni what I am thinking about nowadays, my mind turned to a recent best-seller that both Christian college and public university educators have been talking about for the last three or four years. Alan Bloom complains in The Closing of the American Mind that today’s students talk as if no such things as right or wrong exist; he adds that they have no world-view in which any such values might be grounded, and that as a result they lack a strong sense of personal identity. Instead we hear talk of “alternative lifestyles,” as if morality is simply a matter of personal preferences.

This is hardly new: many alumni will recall from college philosophy courses Sartre’s existentialist theme from the forties and fifties, that since God is dead we now must create our own values. Or the positivist’s claim that, if I say honesty is morally good or dishonesty is wrong, I am in reality just venting my emotions. Someone has called it the “Booh! Hoorah! theory.” Even Christians sometimes talk as if God imposes his law on otherwise morally neutral situations. This implies that morality has nothing to do with the essential nature of human beings and that ours is not in any sense a moral universe. On the other hand stands the claim that we do live in a moral universe, ordered in ways that bear witness to what is good and right. If this is the case, then we do not create our own values, for they are already inherent in God’s creation.

Recently, I have been researching the historical roots and development of our belief in a moral universe. For more years than I like to think, I have been teaching a year-long course on the history of Western philosophy. I am now retracing that story from the standpoint of this topic and, having come to the beginning of the Middle Ages, am hoping to complete the resulting manuscript–along with revisions to my history course–before retirement catches up with me a few years from now.

The story begins with the emerging idea of cosmic justice in Homer and Hesiod, Aeschylus, and Sophocles. A just person and a justly ordered city-state are but microcosms of an entire universe ruled fur just ends. The presocratic philosophers, speculating about such order in the universe, proposed that a cosmic Mind, a logos, lies behind both nature’s laws and the moral life. As a result, concern for the moral improvement of the soul naturally led Plato to his famous theory of forms and the belief that God must be good–a view Aristotle echoes in his claim that everything has purpose, a natural end that is good. And so foundations were laid for theories of natural law, natural rights, and objective moral values that have shaped Western civilization. From this standpoint Bloom is right when he claims that objectively grounded moral values point to an overall world-view, within which framework I can define my own identity.

Our history was, of course, shaped by the convergence of this Greek tradition with the biblical heritage of the Christian church. So my story must also include the interplay of philosophy and theology in the early church, the medievals, the Protestant reformers, and beyond.

But with the rise of modern science it takes a new direction. In an impersonal world of matter in motion, moral concerns seem alien. “Can I take a thing so dead,” Tennyson asks, “Embrace it for my mortal good?” Empirical methods had no way of getting from observable facts to intrinsic values. So ethics became a matter either of subjective feeling or else of predicting desirable consequences. In both cases, subjectivity ruled, relativism resulted, and there was really no such thing as right or wrong. The world-view was in effect that of Nietzsche’s Zarathustra: God is dead, so “we must become the meaning of the earth.”

It is little wonder that voices arose in protest, and Bloom is far from alone. Forty years ago the British Catholic philosopher Elizabeth Anscombe wrote that for half a century the concept of moral law had seemingly been excluded from ethics. Yet, she continued, how could the idea of moral law survive without the idea of a lawgiver? In that sense, the Greeks were closer to the truth than are many of our contemporaries. Even Bloom fails to get that point.

———-

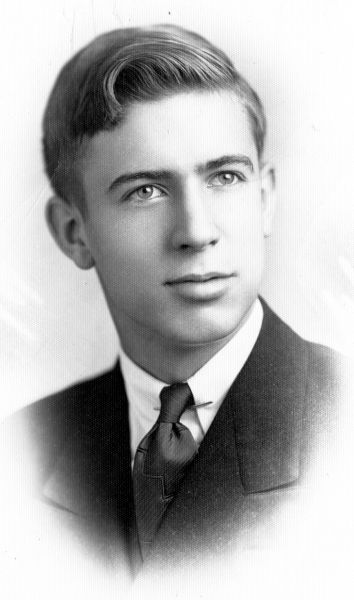

Dr. Arthur F. Holmes is Professor Emeritus and former chair of the philosophy department. A native of England, where he received his early schooling, Holmes completed his education with a Ph.D. from Northwestern University in 1957. He has been the recipient of several awards, including Illinois Professor of the Year presented by the Council for Advancement and Support of Education. Dr. Holmes has authored several books, including, Shaping Character: Moral Education in the Christian College (1991), All Truth is God’s Truth (1977), and The Idea of a Christian College (1975).

On October 30, 1997

On October 30, 1997