The stocky lady in the long black dress, striding confidently on short legs from class to class, was Dr. Elsie Dow, authority on Shakespeare and Browning. Born in Sycamore, Illinois in 1859, she graduated from Wheaton College in 1881. After employment in high schools and academies, she returned to Wheaton in 1889 as Professor of English Language and Literature. In addition to teaching Classics, History, Mathematics and English, she also served as registrar. Dow studied at Harvard, and in 1922, because of her outstanding achievements in literature, Lawrence College conferred upon her the Doctor of Letters degree. Popular on campus, she was in demand off campus, as well, as reader and speaker.

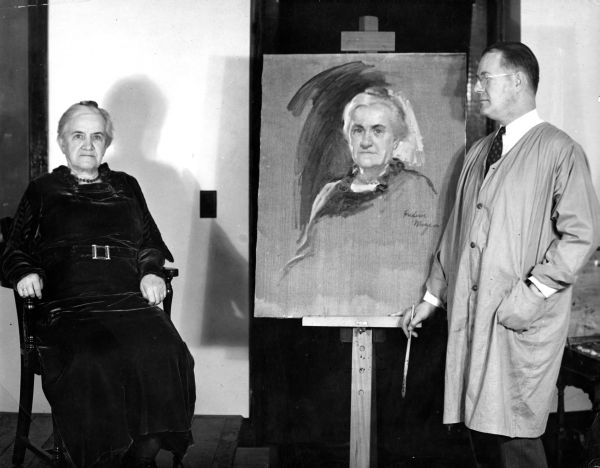

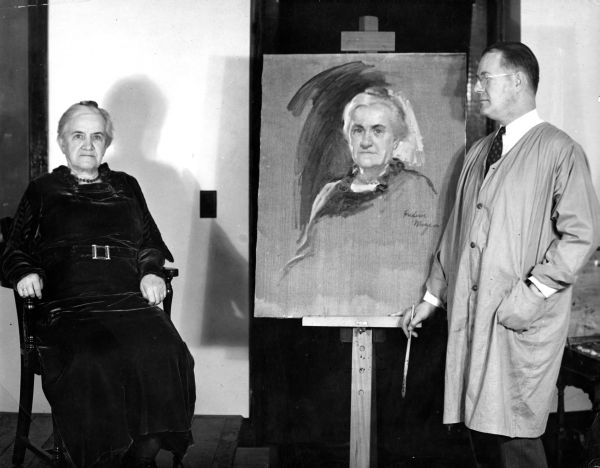

At the 1937 Homecoming chapel Dr. Buswell presided over the unveling of a portrait of Dow done by Frederick Mizen of Chicago. Herman Fischer accepted the painting for the college. After Elsie Dow spoke, Mignon Bollman McKenzie sang a special number composed for the occasion by Marion Downey and Corinne Smith. The piece was a musical setting of Miss Dow’s poem, “Whatsoever Things are Lovely.” The service was concluded with a benediction by Darien Straw.

At the 1937 Homecoming chapel Dr. Buswell presided over the unveling of a portrait of Dow done by Frederick Mizen of Chicago. Herman Fischer accepted the painting for the college. After Elsie Dow spoke, Mignon Bollman McKenzie sang a special number composed for the occasion by Marion Downey and Corinne Smith. The piece was a musical setting of Miss Dow’s poem, “Whatsoever Things are Lovely.” The service was concluded with a benediction by Darien Straw.

For the 1941 inauguration of V. Raymond Edman she wrote:

My word of greeting to our new president is a very sincere welcome from the old to the new. I have been on this campus long enough to have been under the administration of each of our four presidents, and Wheaton has been to me in turn — President Jonathan Blanchard, President Charles Blanchard, President J. Oliver Buswell, Jr. — as it is to me in days to come, President Edman…I see the picture clearly, it is the heroic type. Wheaton will not be Wheaton if it ever loses that type as its head.

Upon her retirement in 1942 Darien Straw wrote:

When Miss Dow began teaching here she was an experienced teacher. Teachers were invited for reasons. I do not know that they ever applied for the job. Schedules were thirty hours a week. Salaries were low and pro-rated, so that the College was kept out of debt by paying all bills, and what was left was apportioned among the teachers with the understanding that accounts were closed at the end of each year. I doubt whether she ever had a written contract for salary yet. She taught all around the curriculum; if a department was short, she could substitute. It is rare for a woman to take a man’s chair and hold it for more than half a century. She did it. Always poised, always sedate, a thousand abstract Christian virtues embodied in the concrete; a walking literary library, with no slang version; among her pupils admired, among her students loved, wherever known and respected; Doctor Dow is thus held in high esteem by the trustees and carries with her ever their benediction and felicitation.

In 1944 100 friends honored Dow on her 85th birthday, visiting her home at 527 Kenilworth. Two outstanding features of the decorated dining room were the large centerpieces of red roses and two two-tier cakes; the latter were brought from Ann Arbor, Michigan. Miss Julia Blanchard assisted with refreshments during the afternoon. Friends and alumni, ranging throughout her 50-year teaching career, offered congratulations. Miss Dow received cards, flowers and gifts from those who could not attend. Special verse messages by Darien Straw and Judge Frank Herrick were read.

She died on October 29, 1944.

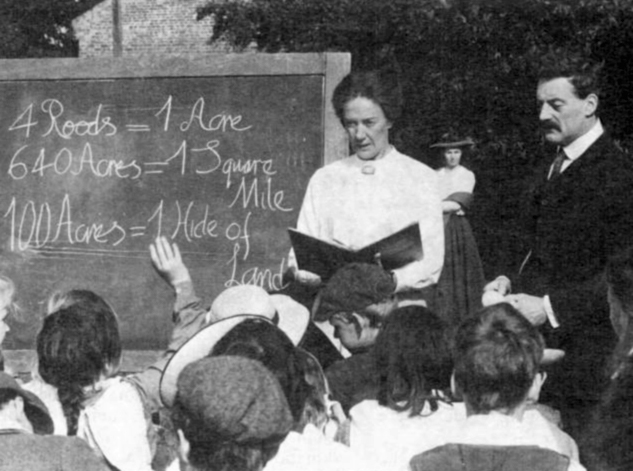

Alan Alexander Milne was born in Kilburn, London, England in 1882 and grew up at Henley House School, a small independent school in London run by his father. One of his teachers was H.G. Wells who taught there in 1889-90. Milne later attended Westminster School and Trinity College, Cambridge, studying mathematics. While at Cambridge Milne edited and wrote for a student magazine, Granta, where he came to the attention of editors at Punch, a humor and satirical magazine. He would later work at Punch as an assistant editor. In 1913 Milne married Dorothy “Daphne” de Selincourt and together they had one child, Christopher Robin Milne, on whom was based the Christopher Robin character of his later Winnie the Pooh books. Milne retired to his farm after a stroke and brain surgery in 1952 left him an invalid. He died in 1956.

Alan Alexander Milne was born in Kilburn, London, England in 1882 and grew up at Henley House School, a small independent school in London run by his father. One of his teachers was H.G. Wells who taught there in 1889-90. Milne later attended Westminster School and Trinity College, Cambridge, studying mathematics. While at Cambridge Milne edited and wrote for a student magazine, Granta, where he came to the attention of editors at Punch, a humor and satirical magazine. He would later work at Punch as an assistant editor. In 1913 Milne married Dorothy “Daphne” de Selincourt and together they had one child, Christopher Robin Milne, on whom was based the Christopher Robin character of his later Winnie the Pooh books. Milne retired to his farm after a stroke and brain surgery in 1952 left him an invalid. He died in 1956.