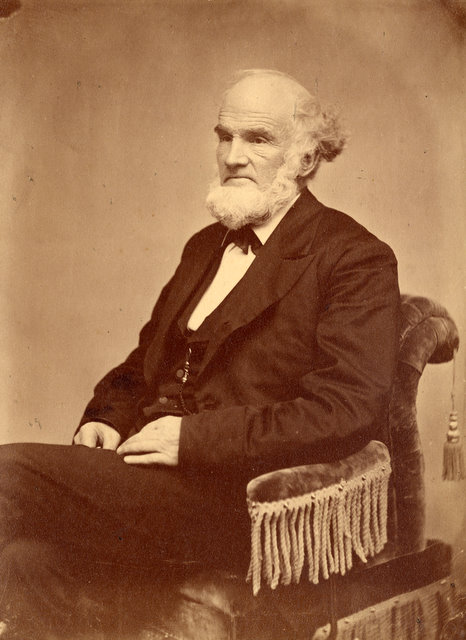

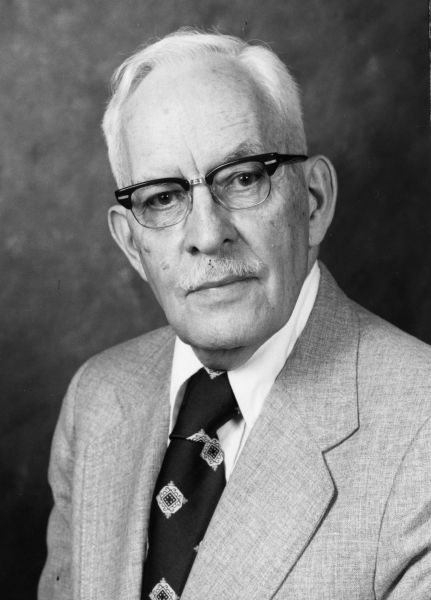

This fine bit of Christology from Dr. Merrill Tenney, former Dean of the Wheaton College Graduate School, appeared in the December, 1958, Alumni Magazine.

In the obscurity of a stable in a cave in Bethlehem of Judea there occurred one of the most ordinary events of history: a baby was born. Nothing could be less spectacular; it is as common as mankind. Every one of us who now lives entered this world by that same gateway, so that this baby was no exception. He did not come from an aristocratic family. Mary, his mother, though of good ancestry, was of Galilean peasant stock, and her husband, Joseph, was a village carpenter. Both were well known to all their neighbors as good but ordinary people, probably neither better nor worse than the average. They had neither power, nor wealth, nor influence. No particular notice was taken of the baby’s arrival, and there was no celebration in His honor. The populace of Bethlehem did not know that He existed.

In the obscurity of a stable in a cave in Bethlehem of Judea there occurred one of the most ordinary events of history: a baby was born. Nothing could be less spectacular; it is as common as mankind. Every one of us who now lives entered this world by that same gateway, so that this baby was no exception. He did not come from an aristocratic family. Mary, his mother, though of good ancestry, was of Galilean peasant stock, and her husband, Joseph, was a village carpenter. Both were well known to all their neighbors as good but ordinary people, probably neither better nor worse than the average. They had neither power, nor wealth, nor influence. No particular notice was taken of the baby’s arrival, and there was no celebration in His honor. The populace of Bethlehem did not know that He existed.

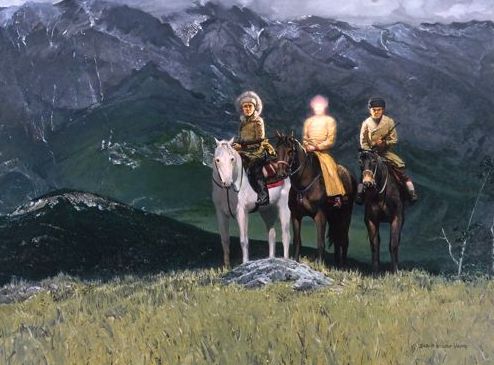

Nevertheless, His birth was a landmark in the history of the world that marked a change in the very method of reckoning time, and that changed the course of empire. While the fact of His birth was not extraordinary, the nature of His birth most certainly was, for both of the Gospels that describe it assert unequivocally that He was born of a virgin. Mary, His mother, officially betrothed to Joseph, but the marriage had not been consummated before He was born. The accounts tell us that His birth was announced by an angelic messenger, and that the Holy Spirit so came upon Mary that her child was called “the Son of God” (Luke 1:35), and the celestial hosts who appeared to the shepherds in the fields of Bethlehem sang of “Glory to God in the highest, and on earth peace, good will toward men,” when He entered the world.

This mingling of the supernatural and the natural, of deity and humanity is the miracle of Christmas. God has entered into the experience of humanity not as a casual visitor, but as a partaker of our flesh will all its limitations and sorrow. “He was in all points tempted like as we are.” Nevertheless, he was not just a victim of fate, for through the vehicle of the human body He labored, taught, died and rose that He might reveal the nature of God to men, and that He might fulfill God’s purpose in saving them. The miracle of Christmas is that in the coming of Jesus, God made himself our Redeemer, and that in the ordinary process of birth a new and supernatural power entered human life. Because He is both God and man, He is able to destroy death and to give eternal deliverance from fear and failure.