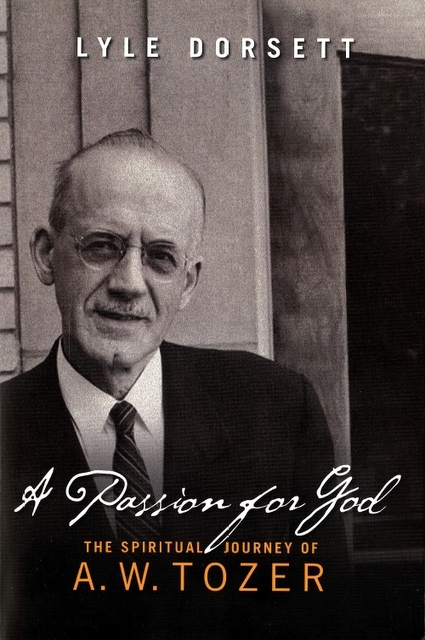

The following passage describes the relationship between A.W. Tozer and Wheaton College and is transcribed from “A Passion for God: The Spiritual Journey of A.W. Tozer” by Lyle Dorsett (Moody 2008).

From 1945 until his death in 1963, Tozer poured seemingly unbounded energy into the younger generation. The Sunday evening services at the church on Union Avenue continued to attract hundreds of students as long as Tozer was there. They came twenty-five miles from Wheaton College, and they drove or took the streetcar from Moody Bible Institute. College-age men and women were eager to listen to an intelligent and articulate speaker who assumed the inerrancy of the Bible and used it to call them to radical obedience.

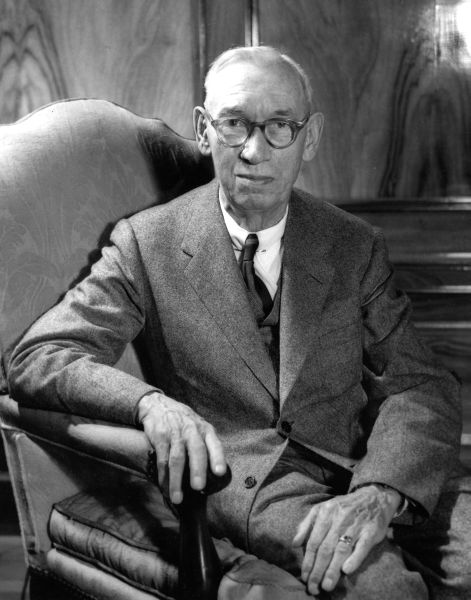

Tozer’s popularity with students on Sunday nights led to other times of interaction with college-age people. Dr. V. Raymond Edman, President of Wheaton College beginning in 1941, became a close friend to A, W. Tozer. The two men shared many experiences and interests. Edman, born in 1900, was three years younger than Tozer. Bespectacled, balding more than Tozer and slightly heavier, Edman served in the United States Army as an enlisted man in World War I. Whereas Tozer was self-educated, Edman worked his way through university, earning a BA from Boston University in 1922. A Spanish major, Edman developed connections with Dr. Paul Rader when he served as head of the C&MA’s Bible Training Institute in Nyack, New York. Through Rader, Edman connected with the Alliance and after marriage he and his wife went to Ecuador as missionaries. Eventually the Edmans returned to the United States because of Raymond’s health, and he went on to earn an (American History) and a PhD (International Relations) from Clark University in Massachusetts.

Tozer’s popularity with students on Sunday nights led to other times of interaction with college-age people. Dr. V. Raymond Edman, President of Wheaton College beginning in 1941, became a close friend to A, W. Tozer. The two men shared many experiences and interests. Edman, born in 1900, was three years younger than Tozer. Bespectacled, balding more than Tozer and slightly heavier, Edman served in the United States Army as an enlisted man in World War I. Whereas Tozer was self-educated, Edman worked his way through university, earning a BA from Boston University in 1922. A Spanish major, Edman developed connections with Dr. Paul Rader when he served as head of the C&MA’s Bible Training Institute in Nyack, New York. Through Rader, Edman connected with the Alliance and after marriage he and his wife went to Ecuador as missionaries. Eventually the Edmans returned to the United States because of Raymond’s health, and he went on to earn an (American History) and a PhD (International Relations) from Clark University in Massachusetts.

In 1937 Dr. Edman joined the faculty at Wheaton College to teach history. In 1941 he was appointed president of the college. Tozer’s name was well known to Edman by the time he we Wheaton, because as a member of the Alliance he had read Tozer’s articles in The Alliance Weekly. The two men met personally by 1940 and became fast friends. Both men understood college women and men and sensed God’s leading to encourage them in their faith. Tozer frequently had Dr. Edman come and preach at Southside Church and he urged the college professor to write for Alliance magazine. Once Edman became president of Wheaton College there was seldom a year that passed–at least until the Tozers moved to Canada in 1959–that the Southside pastor was brought to Wheaton College to speak in chapel.

Tozer shared his pulpit with Raymond Edman, and the latter opened the college podium to Tozer because they manifested almost identical understandings of the Bible. As Alliance men, both fully embraced the denomination’s four pillars of Jesus Christ as Savior Sanctifier, Healer, and Coming King. Beyond this connection, however, both men stood deeply committed to the belief that all born-again Christians are invited by God into a “deeper life” after conversion. Each man had experienced a personal and transformational work of grace after conversion. And while each man knew that the Spirit of Jesus Christ works uniquely with every soul, they nevertheless knew from Scripture, church history, and their personal experience that the Spirit of Jesus Christ desires to continue to grow in and flow through His chosen people in profound, transformational, and God-glorifying ways that are seldom realized by most Christians.

V. Raymond Edman laid out his views on what he saw as the liberating and fulfilling life in a volume titled They Found the Secret (1960). A collective spiritual biography of twenty people, Edman presented cameo portraits and deeper life experiences of notable Christians such as Amy Carmichael and Dwight L. Moody.

Tozer set forth a similar view, albeit not through historical biographies, but in a series of articles he published in the magazine Christian Life that were published in a little book titled Keys to the Deeper Life (1957). Prior to this, Tozer had expressed his views on the ‘deeper life’ in several chapel addresses at Wheaton College–ten in 1952 and one two years later.

Young people loved Tozer in the same way an earlier generation loved D. L. Moody. Like the world-famous nineteenth-century evangelist, Tozer knew how to communicate with young adults, and he had a sacred anointing from the Holy Spirit to reach people’s hearts as well as minds. Like Moody and Edman, Tozer did not push Pentecostal doctrines or the gift of tongues. Instead, people were told that knowing about Jesus Christ, understanding correct doctrine, and being a good student of the Bible are only part of our calling. The Lord wants His people to “know Him” not just “about Him.” in the spirit of John 17:3, eternal life is to know the Father and Jesus Christ whom He has sent. Tozer, like Moody, urged people to enter into a deeper life with Christ. Tozer often spoke these or similar words:

Tens of thousands of believers who pride themselves in their understanding of Romans and Ephesians cannot conceal the sharp spiritual contradiction that exists between their hearts and the heart of Paul. That difference may be stated this way: Paul was seeker and a finder and a seeker still. They seek and find and seek no more. After “accepting” Christ they tend to substitute logic for life and doctrine for experience. For them the truth becomes a veil to hide the face of God; for Paul it was a door into His very Presence… Many today stand by Paul’s doctrine who will not follow him in his passionate yearning for divine reality. Can these be said to be Pauline in any but the most nominal sense?

Tozer went on to explain this further by quoting The Cloud of the Unknowing, which he argued contained a prayer that expresses the core of deeper life teaching:

God, unto whom all hearts be open…and unto whom no secret thing is hid, I beseech Thee so for to cleanse the intent of mine heart with the unspeakable gift of Thy grace, that I may perfectly love Thee and worthily praise Thee. Amen.

Tozer continued:

Who that is truly born of the Spirit, unless he has been prejudiced by wrong teaching, can object to such a thorough cleansing of heart as will enable him perfectly to love God and worthily to praise Him? Yet this is exactly what we mean when we speak about with the “deeper life” experience. Only we mean that it should be literally fulfilled within the heart, not merely accepted by the head.

Words such as these set ablaze the hearts of thousands of young women and men who, admittedly, were longing for something more. Not that they sought emotional highs or spiritual “experiences.” On the contrary, most of the young people at Wheaton College and Moody Bible Institute had encountered enough excesses in the burgeoning Pentecostal movement. This was not their goal. Rather, they wanted to know Jesus Christ better so that they could make Him known to a world of lost and confused souls.

Tozer’s messages to Chicago-area students became famous. Soon he was invited to fundamentalist and evangelical campuses in other places. During the 1940s and 1950s, the Chicago Alliance pastor spoke at St. Paul Bible College (Minnesota) in 1941. He did Spiritual Emphasis Week services at Wheaton College twice in the 1950s, and also at Fort Wayne Bible College (Indiana) in 1948 and 1954, as well as the baccalaureate address at Houghton College (New York) in 1952. He also spoke at Taylor College (Indiana) in 1960 and Nyack College the same year. Wheaton College honored Tozer with an honorary doctorate (LLD) in 1950, and Houghton College bestowed the honorary LLD two years later. Although Tozer never sought to be called “doctor,” he was certainly grateful to be so honored by highly respected Christian colleges like Houghton and Wheaton.

There is no way to measure Tozer’s impact on college people, but the testimonies are nearly legion. Billy Graham remembered going to hear Tozer at the Southside Church several times before he graduated from Wheaton College in 1943, and said he was always deeply blessed, Dr. J. Julius Scott, Professor Emeritus, Wheaton Graduate School, remembered that as a freshman at Wheaton in the early l950s, Tozer’s challenges to “know God Himself,” not just “about God,” left an indelible mark on his soul.23 In the same vein, the late Dr. Bernard King, who graduated from St. Paul Bible College in 1941, said he first met Tozer personally at the college commencement the year we entered World War II. He credited his relationship with Tozer that began at college as being extremely important in his spiritual life and ministry.

Dr. Tozer had a range of influence on high school–age youth that rivaled his impact on college people. He frequently spoke at Youth for Christ rallies on foreign missions and radical commitment to Jesus Christ. Likewise he became one of the most popular speakers at Christian and Missionary Alliance Youth gatherings in places such as New York and Cincinnati, as well as Chicago.