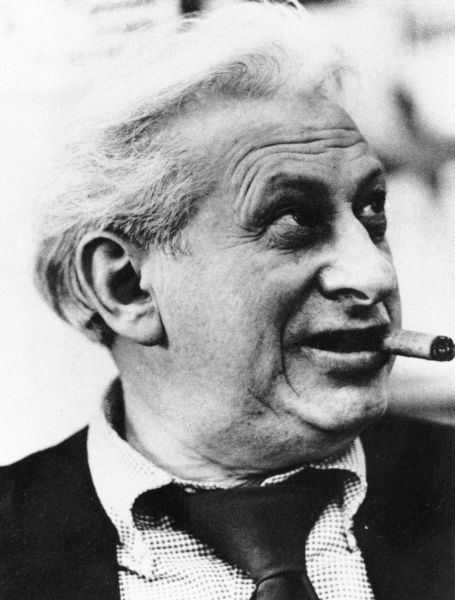

Chicago’s distinctive personality is a complex amalgamation of revolutionary architecture, excellent food, famous streets and most importantly, its multitudinous colorful citizens, wise-cracking and hardworking. For decades the man who most perfectly captured the spirit of the Windy City, serving as its most loyal ambassador, was Louis “Studs” Terkel.  A graduate of the University of Chicago and the Chicago Law School, he acted on stage and radio and wrote scripts for WGN, among many other jobs. Forever curious, he hosted his own radio show on WFMT, enthusiastically interviewing scores of fascinating writers, actors and politicians, signing off with his signature, “Take it easy, but take it.” He acquired his nickname from James T. Farrell’s trilogy, Studs Lonigan, about a Southside Irish family struggling during the Depression.

A graduate of the University of Chicago and the Chicago Law School, he acted on stage and radio and wrote scripts for WGN, among many other jobs. Forever curious, he hosted his own radio show on WFMT, enthusiastically interviewing scores of fascinating writers, actors and politicians, signing off with his signature, “Take it easy, but take it.” He acquired his nickname from James T. Farrell’s trilogy, Studs Lonigan, about a Southside Irish family struggling during the Depression.

Terkel was probably best known for conducting oral interviews, collected as transcripts in a series of books. Division Street: America (1966) explores urban conflicts of the 1960s. The Good War: An Oral History of World War II won the 1985 Pulitzer Prize for nonfiction. His autobiographical writings are contained in three volumes, Talking to Myself: A Memoir of My Times, (1977), Touch and Go (2007), and P.S.: Further Thoughts From a Lifetime of Listening (2008).

Visible in Chicago and nationally, Terkel was widely connected with many prominent figures, so it is not surprising that he knew Dr. Clyde Kilby, professor of English at Wheaton College and founder of the Marion E. Wade Center, housing the manuscripts of C.S. Lewis, J.R.R. Tolkien and five additional British writers. What is somewhat surprising is an inscription Terkel wrote for Kilby and his wife, Martha, in the front flyleaf of American Dreams: Lost & Found (1980):

For Clyde and Martha Kilby — How, with such delight, I remember our meeting — your godlike simplicity — but mostly your effect on Nell’s life — and helping her become the wondrous human she is.

With a great deal of respect and affection, Studs Terkel.

According to Terkel’s close friend, film critic Roger Ebert, the indefatigable journalist was “a contented, not an outspoken, atheist.” Considering that, it is intriguing that Terkel recognizes and commends the Kilbys for their “godlike simplicity.” Though the full story behind the inscription is unknown to the Archives, it is fully appropriate that two men who collected stories and relished good storytelling intersected with such intensity, however briefly.

Studs Terkel died at 96 in 2008.