Ray Bradbury, who died on June 5, 2012, stirred deep wells of wonder among his readers for over seventy years, writing poetry, novels and short stories. Titles such as Dandelion Wine and Fahrenheit 451 continue to inspire and provoke. His influence is enormous, extending from literature to film and television, as he occasionally functioned as creative consultant to such entertainment pioneers as Walt Disney and Rod Serling, creator of The Twilight Zone. From time to time Bradbury’s cosmic reach extended to the world of Evangelicalism, Wheaton College in particular.

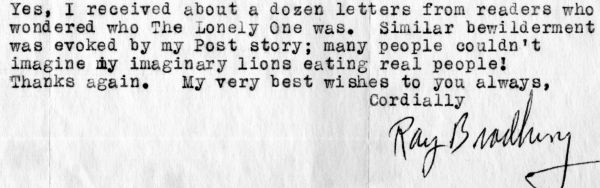

Muriel Fuller, author, prominent editor and 1925 Wheaton grad, corresponded with Bradbury in 1950. In his reply, archived at Wheaton College Special Collections (SC-87), Bradbury thanks Fuller for her positive feedback regarding his short stories and encouragement that he should consider collecting them, which he had already recently done with The Martian Chronicles and The Illustrated Man.

Muriel Fuller, author, prominent editor and 1925 Wheaton grad, corresponded with Bradbury in 1950. In his reply, archived at Wheaton College Special Collections (SC-87), Bradbury thanks Fuller for her positive feedback regarding his short stories and encouragement that he should consider collecting them, which he had already recently done with The Martian Chronicles and The Illustrated Man.

A notable Christian commentator on Bradbury’s themes is Calvin Miller (SC-24), former pastor, current Professor of Preaching and Pastoral Ministry at Beeson Divinity School, poet and author of several fantasy novels, whose papers are archived at Wheaton College. Miller argues that Bradbury, claiming no specific beliefs, nonetheless stimulates intuitive feelings that allow for the development of a rich, expansive faith. The following excerpts are derived from Miller’s essay, “Ray Bradbury: Hope in a Doubtful Age,” included in Reality and the Vision: 18 Contemporary Writers Tell Who They Read and Why (1990):

Sometime in seminary Bradbury first fell into my world (or perhaps I fell into his). The scholarly tedium of learning how to be “truly spiritual” can coat all things bright and beautiful with dullness, and somewhere between hermeneutics and apologetics I needed something to wake my imagination to wonder…And Bradbury, while not often explicit about the content of his faith, professes a glorious, self-declaring confidence in God. I have scarcely heard Pentecostals be more rapturous than was Bradbury’s exuberant declaration on that tenth anniversary of the Apollo landing…My own concept of God can never remain static after coming into contact with the fictional output of a man driven by such near-spiritual forces, a writer with such a dynamic view of the God who leads man toward scientific maturity. Bradbury, at his best, is not only a prophet for a depressed people; he is a kind of deliverer, awakening our sensibilities…But hope is the real stuff of Bradbury. A Christian positivism pervades his works and that quality, more than anything, marks his work as distinctively Christian in tone. In the glorious finale to Something Wicked This Way Comes, Jim Nightshade is brought back to life by a father and son dancing and singing “Camptown Races.” Joy is the only cure for every monstrous evil work…We never “get to” the future — it beckons us, never to receive us. But it is always there and it is a place of hope! Such is the insight we need in order to get up in the morning. This insight, which I sucked from the very marrow of Bradbury’s bones, is also the ultimate promise of Christ. Christ is alive — His Living Being is the transforming Easter news! But Jerusalem — made new — is descending: this living vision is the hope that guarantees our future.

In 2007, staff from Wheaton College conducted a phone interview with Bradbury from his home in Los Angeles, inquiring about a possible connection between him and C. S. Lewis, whose papers are archived at the Wade Center. Both men wrote about the planet Mars, publishing in American pulp magazines of the 1940s and ’50s. In one book and two unpublished letters, Lewis commends Bradbury as “the real thing” as opposed to less gifted pulp hacks, speaking highly of his “poetic” style. However, Bradbury, stating that he “took Lewis’s Screwtape Letters everywhere I go,” had not read any of the Oxford professor’s other books, nor had he met or corresponded with him.

The papers of Calvin Miller and Muriel Fuller, located in the Special Collections on the third floor of the Billy Graham Center, are available to researchers.