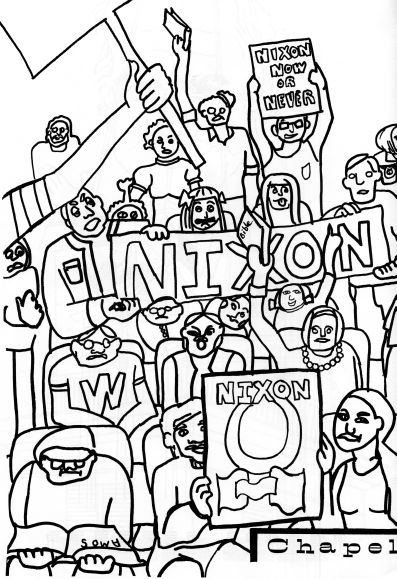

George McGovern, historian, senator and representative from South Dakota, died on October 21, 2012. Forty years ago, on October 11, 1972, he spoke at Wheaton College, a rather unlikely campaign stop for the Democratic presidential nominee against Republican Richard Nixon.  The event was initially suggested by McGovern’s staff, asking for a venue in which he might engage Evangelicals. Activist Jim Wallis, attending Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, was asked to organize the senator’s visit, arranging a breakfast with prominent Christian leaders, in addition to an engagement at Wheaton College. “Actually,” writes Wallis, “the Wheaton Student Council, which issued the invitations to both candidates, accidentally switched the letters, sending Nixon’s by mistake to McGovern.” However, only McGovern accepted. A quiet man raised in a devout Methodist family, McGovern soon found himself in the pulpit of Edman Chapel, standing before an atypically divided house. A few supportive students cheered his unpopular anti-Vietnam War position, but many more booed, waving pro-Nixon banners.

The event was initially suggested by McGovern’s staff, asking for a venue in which he might engage Evangelicals. Activist Jim Wallis, attending Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, was asked to organize the senator’s visit, arranging a breakfast with prominent Christian leaders, in addition to an engagement at Wheaton College. “Actually,” writes Wallis, “the Wheaton Student Council, which issued the invitations to both candidates, accidentally switched the letters, sending Nixon’s by mistake to McGovern.” However, only McGovern accepted. A quiet man raised in a devout Methodist family, McGovern soon found himself in the pulpit of Edman Chapel, standing before an atypically divided house. A few supportive students cheered his unpopular anti-Vietnam War position, but many more booed, waving pro-Nixon banners.

Wallis had asked black evangelist Tom Skinner to introduce McGovern:

…Skinner…was a strong supporter of the senator and also, remember, I was banned from speaking at Wheaton. In an embarrassing moment, the students almost booed Skinner off the stage. McGovern’s aides were astonished.

When the senator finally came out, the Wheaton students booed him too — a candidate for President of the Unites States.

Despite a rude reception from this portion of the campus community, McGovern calmed the noise, speaking knowledgeably and even charmingly, stating that he had once considered attending Wheaton College, but did not because his family could not afford it. Wallis recalls: “McGovern then…gave a speech that was perhaps the best I have ever heard about the relationship between Christians values and public life.”

The speech is heard here.

Wallis also remembers:

Wallis also remembers:

…a question McGovern got from an aggressive professor of Christian apologetics who asked the senator how somebody who attended the liberal Garrett Theological Seminary could have an adequate view of the fallen state of human nature. McGovern surprised the evangelical leaders by giving a theologically knowledgeable and biblically balanced exegesis of the Apostle Paul’s view of the human condition and then ended with a joke that broke up the house: “So because I don’t fully subscribe to the theology of complete human depravity and because Richard Nixon practices it, you’re going to vote for him?”

According to English professor Paul Bechtel, “Challenging ideas were set before the students with conviction, with charitable fairness, with no evidence of hollow political cliches.” Alas, McGovern lost the election with 17 electoral votes against Nixon’s 520. McGovern’s books include Abraham Lincoln (2008) and What It Means to Be a Democrat (2011).

Jim Wallis’s essay, “The George McGovern I Remember,” is published in the October 25, 2012, online edition of Sojourners: Faith in Action for Social Justice. The papers of Jim Wallis (SC-109) and Sojourners (SC-23) are housed in the Wheaton College Special Collections, available to researchers.

The cartoons are scanned from Coloring Book of Wheaton College, Spring 1973.