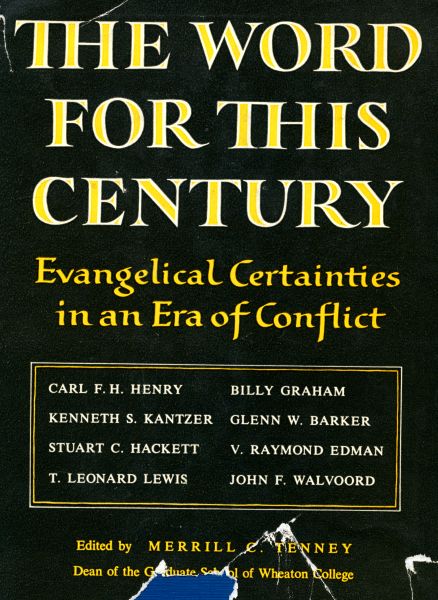

This Christmas meditation, written by V. Raymond Edman, originally appeared as a tract called “Meet Mr. Scrooge,” published by Moody Press.

Ebeneezer Scrooge. Who has not met him? To be sure, he never really existed except in Dickens’ A Christmas Carol, one of the most delightful Christmas stories ever told. Scrooge is so vividly portrayed that his name has become a part of our language. Since we first learned about him, we have known every stingy old miser as a scrooge. But our acquaintance with him may be superficial. We meet so many characters in Dickens’ immortal story that we may fail to follow Mr. Scrooge to the end, and the conclusion is the real point and climax of the tale. We are intrigued by Marley’s ghost with his clanking chains. We are pleased with the cheerful nephew of Ebenezer who at first had no warming influence on his greedy old uncle. We are stirred by Bob Cratchit and his delightful family, especially Tiny Tim with his enthusiastic word, “God bless us every one!”

Then there are those ghosts, each with a message to Scrooge. The Ghost of Christmas Past brought back the recollection of happy schooldays and the reminder of merry Christmas Eves of long past when Scrooge was an apprentice in the office of old Fezziwig. There was even the reminder of an old love affair that never materialized. The bittersweet nostalgia of the yesterdays! The Ghost of Christmas Present took the old skinflint to the happy scenes in the humble Cratchit home the preparation for dinner, the arrival of Father Bob and his little crippled son from the church service, the gratitude of all for God’s goodness despite Bobs poor wages. A delightful scene in merry old England! But the Ghost of Christmas Future had only sadness for Scrooge. The Cratchit home was silent and tearful, and Tiny Tim, who might have lived had there been money for medical help, was no longer there. From there the Ghost took the penitent and fearful Scrooge to a deserted cemetery and pointed to a solitary grave marked with the name Ebenezer Scrooge.

No, never! How could he ever face the dismal and doleful prospect pictured in that headstone? As Scrooge poured out his protest and clung to the arm of the Ghost Future, he came to consciousness, clinging to the bedpost in his own room. It had all been a dream. But life is not a dream. It is very real. For us there is the memory of yesterday’s Christmases with the message: “God so loved the world, that he gave his only begotten Son, that whosoever believeth in him should not perish, but have everlasting life” (John 3:16). We have today, and the Bible reminds us, “Now is the accepted time; behold, now is the day of salvation” (II Cor. 6:2). “Believe on the Lord Jesus Christ, and thou shalt be saved” (Acts 16:31). For the future the Bible goes on to say, “It is appointed unto men once to die, but after this the judgment” (Heb. 9:27). The time to prepare for that certainty is right now.

Meet Mr. Scrooge.

Meet yourself.

Of course you are not the stingy, grasping old miser of A Christmas Carol, but like him you face the prospect that ahead lies the grave and the beyond! Like old Scrooge, you can be transformed, not by New Year’s resolutions but by becoming a child of God in receiving the Lord Jesus Christ. Then the present takes on joy and new meaning, and you can face the future unafraid! “As many as received him, to them gave he power to become the sons of God” (John 1:12).

But when William Leslie left his position in 1961 as assistant pastor of Moody Church, serving under Dr. Alan Redpath, to lead the struggling assembly, the district was severely blighted, collapsing beneath the weight of decrepitude, poverty and racial tensions. Leslie, a graduate of Wheaton College, realized that he must not only preach to touch the spirit, but he must also address the material welfare of his parish.

But when William Leslie left his position in 1961 as assistant pastor of Moody Church, serving under Dr. Alan Redpath, to lead the struggling assembly, the district was severely blighted, collapsing beneath the weight of decrepitude, poverty and racial tensions. Leslie, a graduate of Wheaton College, realized that he must not only preach to touch the spirit, but he must also address the material welfare of his parish.