Born into a musical family and the daughter of a prominent music merchant, Vida Chenoweth and her twin sister Vera gained a wide knowledge of musical instruments early in life.  Their musical talent manifested itself in twin performances of two — piano works, clarinet and later, marimba duos. Along with their two brothers, all four children were literate in music before attending school. Public school, attended in Enid, Oklahoma, was supplemented by batteries of teachers and lessons in dance, acrobatics, music, painting and drawing and sports.

Their musical talent manifested itself in twin performances of two — piano works, clarinet and later, marimba duos. Along with their two brothers, all four children were literate in music before attending school. Public school, attended in Enid, Oklahoma, was supplemented by batteries of teachers and lessons in dance, acrobatics, music, painting and drawing and sports.

Undergraduate studies were at William Woods, then a liberal arts junior college for women, and at Northwestern University’s School of Music. It was during her senior year at Northwestern that Vida suffered the loss of her twin sister. Heart surgery, then in its infancy, was performed on both girls. Vera died in surgery and Vida, after 6 months of painful deliberation, underwent the same surgery in Boston. In her case, it was a complete success. A year later she was touring the Midwest giving solo recitals under auspices of the University of Wisconsin.

A short biographical sketch tends to minimize the struggle to attain, but Chenoweth’s struggle was not in competing with other marimbists. Her competition was with the performers on traditional instruments, and worst of all, she was fighting a blind prejudice against her instrument because of its non-European ancestry. It was a shock to the musical world to hear Chenoweth play the marimba as a classical instrument. It was in the marimba’s favor that Andres Segovia had earned a respected place for the guitar on the concert stage. Audiences were learning that it is the artist, not the instrument, which creates music.

During Chenoweth’s fledgling years in Chicago one goal was foremost, to find a deserved niche for the marimba in serious music circles. Older musicians recognized her talent and the marimba’s potential, but there was no management, no subsidization, no publicity except by word of mouth, and not one musical competition open to her as a marimbist. Even the American Conservatory where she was a graduate student did not permit her to audition for her class’s graduation concert. She made a living by giving marimba lessons in the north shore suburbs and taking part-time jobs in the Loop. Rather than compromise her artistic standards, she earned money outside of music as a typist, census-taker, switchboard operator, waitress and so on. She worked for two years to save enough to hire the Chicago Art Institute’s Fullerton Hall where she gave in 1956 the first public recital of works composed for the marimba. At this recital her original technique for playing polyphonic music was first heard publicly. Chicago’s leading music critic Felix Borowski wrote for the Sun Times:

During Chenoweth’s fledgling years in Chicago one goal was foremost, to find a deserved niche for the marimba in serious music circles. Older musicians recognized her talent and the marimba’s potential, but there was no management, no subsidization, no publicity except by word of mouth, and not one musical competition open to her as a marimbist. Even the American Conservatory where she was a graduate student did not permit her to audition for her class’s graduation concert. She made a living by giving marimba lessons in the north shore suburbs and taking part-time jobs in the Loop. Rather than compromise her artistic standards, she earned money outside of music as a typist, census-taker, switchboard operator, waitress and so on. She worked for two years to save enough to hire the Chicago Art Institute’s Fullerton Hall where she gave in 1956 the first public recital of works composed for the marimba. At this recital her original technique for playing polyphonic music was first heard publicly. Chicago’s leading music critic Felix Borowski wrote for the Sun Times:

“…remarkable. Moreover, the performer is blessed with fine musical taste. The nuances obtained were of moving beauty.”

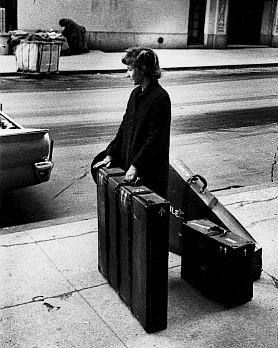

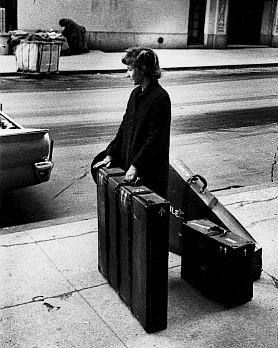

Soon the advice to go to New York was unanimous. Disassembling the marimba and packing it into five 50-pound cases, young Chenoweth departed alone for New York. Her only letter of introduction was written by Rudolph Ganz to the Steinways.

It was not hard to obtain an opportunity to audition at Steinway Hall, but it was hard to find any accommodation in the city which allowed one to practice. The taxi fare to the “Y” was more than anticipated. They refused her instrument, so leaving her 250-pounds of marimba lined along the curb, she began phoning every conceivable listing that might take a musician, all to no avail. There wasn’t enough money for a hotel, and she had no bank account, no affiliations, no relatives. The more hopeless the situation became, the more her tears flowed. One last call to a music student she had known in Chicago at last offered a roof.

It was not hard to obtain an opportunity to audition at Steinway Hall, but it was hard to find any accommodation in the city which allowed one to practice. The taxi fare to the “Y” was more than anticipated. They refused her instrument, so leaving her 250-pounds of marimba lined along the curb, she began phoning every conceivable listing that might take a musician, all to no avail. There wasn’t enough money for a hotel, and she had no bank account, no affiliations, no relatives. The more hopeless the situation became, the more her tears flowed. One last call to a music student she had known in Chicago at last offered a roof.

In later years the personnel at Steinway Hall and Chenoweth chuckled together over her audition there for management. All the leading concert managers had offices in Steinway Hall, and the way to be heard was to play for them in the recital hall. In grey knee-sox, sandals and drndl skirt, she pushed her marimba cases one by one across the sidewalk from a Checker cab and tied up pedestrian traffic for 10 minutes when one of the cases got stuck in the revolving door. In the recital hall, the managers exhibited their caution by sending their secretaries downstairs to hear the audition. Leaping into a virtuosic Bach number so astonished and excited the secretaries that Chenoweth then sat and waited while they fled to get their bosses to listen. From this moment, audiences demanded Bach of her though she preferred to base her career on new music for the marimba. Her respect for the perfection of Bach’s work is reflected in her refusal to arrange his works; she performed his music note-for-note as he wrote it.

With the premiere of Robert Kurka’s concerto for marimba and orchestra in Carnegie Hall, Hew York, in 1959, the critics of every New York newspaper, every music magazine and of Time magazine as well, wrote rave reviews. It was that event which led to invitations to play throughout the world.

Vida Chenoweth has played on every continent. She made the first recording of marimba music in 1962, for Epic Records. At that time, every major work for marimba (20 in all) was composed for her with the exception of Paul Creston’s Concertino For Marimba and Orchestra, composed before Chenoweth played the marimba. At that time, she was the only career marimbist to have been guest soloist with major orchestras and in major concert halls. In Europe, as it had been earlier in New York, the critics’ preconceived ideas of the marimba dissolved, and praise swung from reverence to ecstasy.

The calendar events that most people recall in their own lives are all but forgotten in Chenoweth’s collage of accomplishments. She seldom remembers her own birthday. The influence of great minds and artists, the times when death was close, grief, an awakening to new spiritual depths, the ability to transfer from one contrastive culture to another, these are the shaping forces of her biography. She is today equally at home in the town of Enid where she was born, a grass-hut village in New Guinea; Chicago where she worked for years in bible translation work, Paris, New York, Guatemala, New Zealand or on the sea.

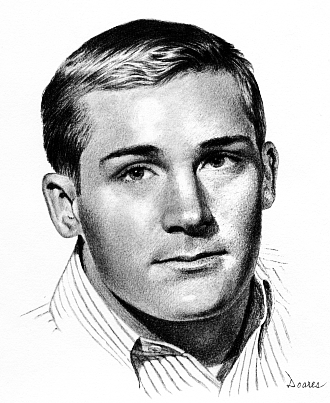

Erwin Paul (Zeke) Rudoph II was a relaxed, vibrant young man of twenty, a student of English literature who also adored sports, particularly baseball. He possessed many friends and much promise. In 1967, after experiencing persistent vision impairment, fatigue and unsteady balance, he consulted his doctor. Enduring one exam after another, Zeke at last received the shocking prognosis. He had developed multiple sclerosis, an incurable disease. In this case, terminal.

Erwin Paul (Zeke) Rudoph II was a relaxed, vibrant young man of twenty, a student of English literature who also adored sports, particularly baseball. He possessed many friends and much promise. In 1967, after experiencing persistent vision impairment, fatigue and unsteady balance, he consulted his doctor. Enduring one exam after another, Zeke at last received the shocking prognosis. He had developed multiple sclerosis, an incurable disease. In this case, terminal.