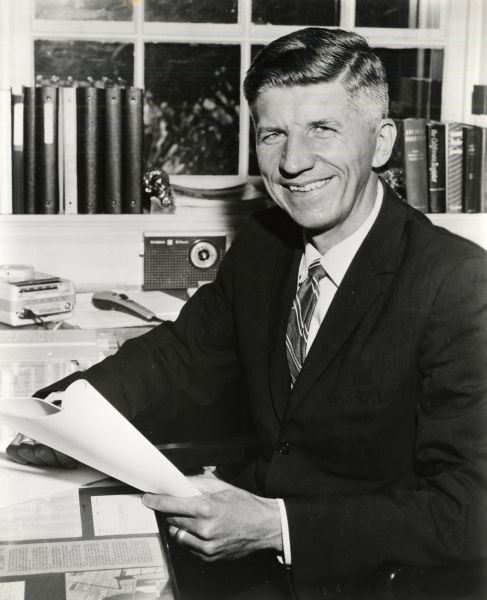

This remembrance by Herb Jauchen ’40 is the first in a series published by Wheaton College Alumni magazine, beginning January, 1966. He served as Vice President of Westmont College and Vice President of advertising for Christian Life Publications. Previously he had managed department stores in Oregon for 13 years, following five years in the US Army during WW II. For two years, 1969-70, he was the Wheaton National Alumni Fund Chairman.

This remembrance by Herb Jauchen ’40 is the first in a series published by Wheaton College Alumni magazine, beginning January, 1966. He served as Vice President of Westmont College and Vice President of advertising for Christian Life Publications. Previously he had managed department stores in Oregon for 13 years, following five years in the US Army during WW II. For two years, 1969-70, he was the Wheaton National Alumni Fund Chairman.

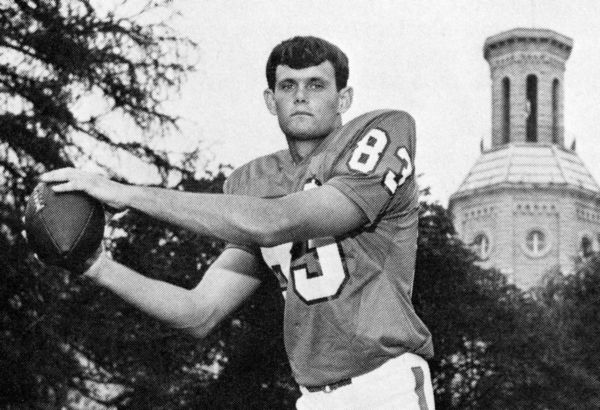

While many rightfully attribute their current successful positions to praying mothers, fathers, parents or Christian homes, the Lord knows I must honestly attribute all of my present blessings to the life He began and shaped for me during four years at Wheaton College, made possible by the faithfulness and dedication of the college family unto God. Those were the lean, post-depression years of the late ’30s, and many of us at that time (interestingly, including most of the then-struggling varsity teams) knew what 40-50-hour work weeks meant, along with tiring practices and full academic schedules.

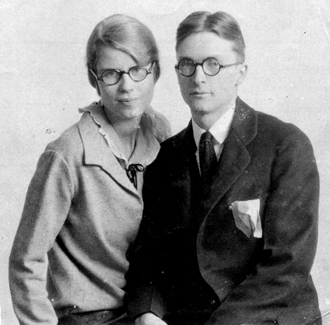

From the beginning, for me, a young man without a home, who even then already had seen much of life in the raw, Wheaton quickly became my home. It began with the warm welcome of upperclassmen like Dayton Roberts, Roger McShane and Bob Lazear and ended, physically, after four years of warm friendship and acceptance by a host of faculty, administration and students alike – four of the happiest and most memorable years of my life. The most important event of those years of many recognitions and awards, however, was the joy, late in Junior year, along with the girl who later became my wife, Joanna Cochran, of being introduced to and receiving Jesus Christ as my personal savior. Strangely, I had been at Wheaton nearly three full years before anyone personally and individually explained Jesus Christ to me. Late one May evening, the faithfulness of Evan Welsh was again used of God, as it has been innumerable times before and since, in leading Joanna and me to a saving knowledge of Jesus Christ. Our lives were completely changed from that time on. Yes, above all, Wheaton College was used not only to lead me into the Christian life but also to give me a wonderful, God-honoring wife and mother of our five children, was well as a sound Christian and academic education. In addition, Wheaton has given me true and tested friends from both faculty, administration and student body alike – V.R. Edman, K.B. Tiffany, Ed Coray, Don Kennedy, Manly Wilcox and many others – who have continued faithful through the years, even as they were during often-difficult undergraduate days.

Almost daily, also, in some 25 years of military, business and Christian service experience, has come to mind and use some of the rich lessons of life first learned in the classrooms, athletic events and campus activities of college days. For truly God has been good in giving knowledge and wisdom to raise up a Christian home and family, following His precepts and playing according to the rules of the game both in home and business. Never having had a Christian home before attending Wheaton, it is thrilling to see my children enjoy the benefits of lessons first taught me there. Recently, my 19-year-old son John wrote that he had just realized my own ultimate success would be measured by the success of my children, above all, spiritually. It was especially gratifying to have that letter come from Wheaton, where he is now in his second year, earning his own way also, by choice, and already learning many more of life’s rich lessons that can be so well learned there. It is our prayer that his younger brothers and sisters also will be able to attend Wheaton and continue on to the mission field, even as John and his older sister Jan are presently planning to do.

The theme of the Wheaton Centennial was the faithfulness of Wheaton to the cause of Christ. I thank God for that faithfulness – of its founders, its faculty, administration, and alumni – not only through past years, but also today, in this era of intellectual unrest, and I pray what will be tomorrow should our Lord tarry. Only by this continuing faithfulness, which has done so much for me, can my children and thousands of other children who will attend Wheaton in the years ahead have the opportunity of being blessed and privileged in beginning life’s journey on their own on sound Christian principles, precepts and learning – for His honor and His glory.