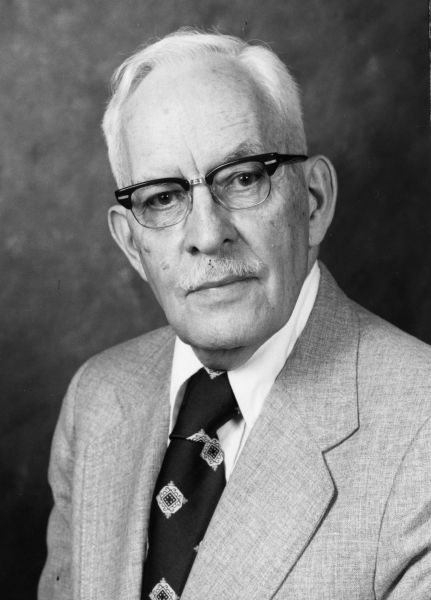

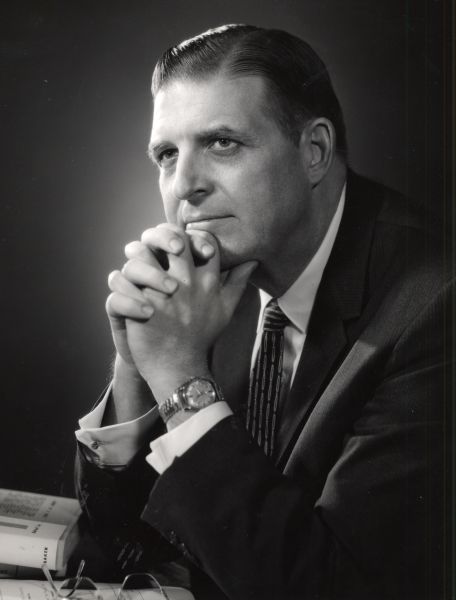

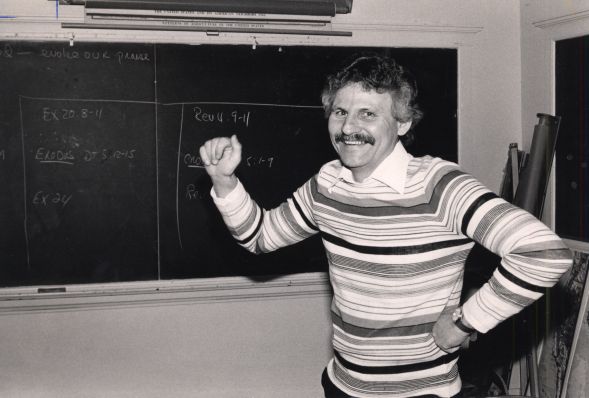

One of the more controversial professors at Wheaton College was Dr. Robert E. Webber, who influenced a generation of students and a large segment of evangelicalism. Raised in a Baptist church in Pennsylvania, he attended Bob Jones University in the late 1950s before enrolling at Reformed Episcopal Seminary, finishing in 1960 his graduate education at Covenant Theological Seminary. He began teaching theology at Wheaton College in 1968. Youthful, energetic and sympathetic to the concerns of students, he was a popular and highly effective lecturer. As he studied ecclesiastical history, its variable trends and moods, Webber perceived that vital practices had been ignored or recklessly tossed aside during the Reformation.

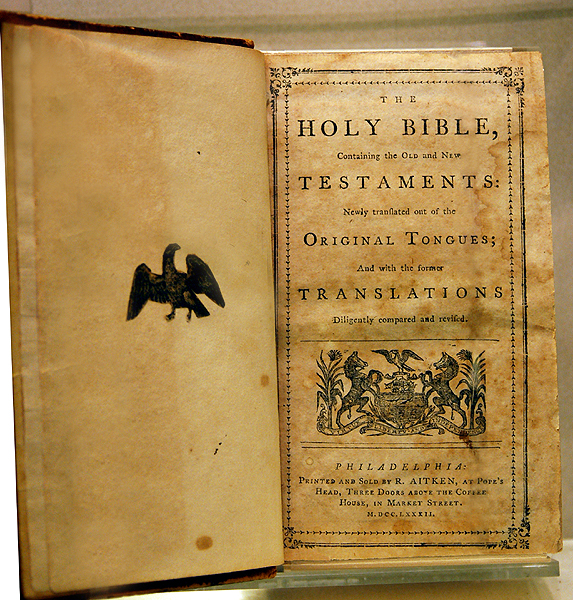

In 1978 he published Evangelicals on the Canterbury Trail, a collection of autobiographical essays by Webber and former evangelicals who gradually adopted Anglo-catholic or Catholic forms of worship. When released the book generated considerable heat among evangelicals who felt that Webber had betrayed the Protestant faith. Eventually, however, it was recognized that his pioneering research opened doors for fresh approaches to church life, whether liturgical expressions were adopted or not. Closely studying the permutations of Christian worship, Webber wrote or edited several additional books dealing with the history and function of liturgy, including Worship is a Verb, Blended Worship and the seven-volume Complete Library of Christian Worship. During his later career he concentrated on the writings of the Church Fathers, attempting to draw from their treatises insights for contemporary contexts. This interest is reflected in the Introduction to Journey to Jesus: “The model of evangelism proposed in this book is a resurrection of the seeker model…that originated in the third century…It speaks particularly to the current search for an effective style of evangelism in a world dominated by postmodern thought, a church living in a post-Constantinian society, and the challenge to overcome the resurgence of pagan values.” Webber was Director of the Institute for Worship Studies. At the time of his death in 2007, he was the William R. and Geraldyn B. Myers professor of ministry at Northern Seminary in Lombard, Illinois.

In 1978 he published Evangelicals on the Canterbury Trail, a collection of autobiographical essays by Webber and former evangelicals who gradually adopted Anglo-catholic or Catholic forms of worship. When released the book generated considerable heat among evangelicals who felt that Webber had betrayed the Protestant faith. Eventually, however, it was recognized that his pioneering research opened doors for fresh approaches to church life, whether liturgical expressions were adopted or not. Closely studying the permutations of Christian worship, Webber wrote or edited several additional books dealing with the history and function of liturgy, including Worship is a Verb, Blended Worship and the seven-volume Complete Library of Christian Worship. During his later career he concentrated on the writings of the Church Fathers, attempting to draw from their treatises insights for contemporary contexts. This interest is reflected in the Introduction to Journey to Jesus: “The model of evangelism proposed in this book is a resurrection of the seeker model…that originated in the third century…It speaks particularly to the current search for an effective style of evangelism in a world dominated by postmodern thought, a church living in a post-Constantinian society, and the challenge to overcome the resurgence of pagan values.” Webber was Director of the Institute for Worship Studies. At the time of his death in 2007, he was the William R. and Geraldyn B. Myers professor of ministry at Northern Seminary in Lombard, Illinois.