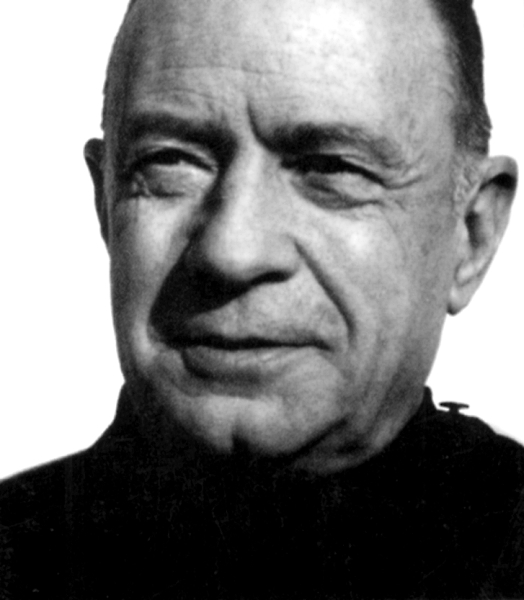

Anyone who has read Malcolm Muggeridge extensively will be familiar with the recurring themes which he tended to call on, either in articles, speeches or books. The clear favorite was the rather overused quote from Blake, making the distinction between seeing with and seeing through the eye. Another was describing himself as a vendor of words, just as St. Augustine had done. But of course, another recurring theme was gargoyles and steeples.

Let’s think of the steeple and the gargoyle. The steeple is this beautiful thing reaching up into the sky admitting as it were, its own inadequacy–attempting something utterly impossible–to climb to heaven through a steeple. The gargoyle is this little man grinning and laughing at the absurd behaviour of men on earth, and those two things both built into this building to the glory of God… [The gargoyle] is laughing at the inadequacy of man, the pretensions of man, the absolute preposterous gap–disparity–between his aspirations and his performance, which is the eternal comedy of human life. It will be so until the end of time you see…Mystical ecstasy and laughter are the two great delights of living, and saints and clowns their purveyors, the only two categories of human being who can be relied on to tell the truth; hence, steeples and gargoyles side by side on the great cathedrals. ………. (Interview with William F. Buckley “Firing Line” television show, 1978)

One of the results of the Muggeridge Rediscovered conference in 2003 was the inception of the Malcolm Muggeridge Society. Formed on the 100th anniversary of Malcolm Muggeridge’s birth, the Society seeks to provide a focus for all worldwide who have a continuing interest in his life as journalist, author, broadcaster, soldier-spy and Christian apologist. The many mentions of Gargoyles, either by Muggeridge himself or in the writing of others about him, explain the aptness of the title for the mouthpiece of the Society, The Gargoyle.

Gargoyles have been around for thousands of years, some of the earliest known forms of gargoyle have been found in ancient Roman and Greek ruins. Originally fabricated in terra-cotta, later figures were carved of wood, yet a complete shift to stone took place by the 13th century. The term gargoyle is a contraction from the Latin gurgulio and the Old French gargouille, sharing an obvious root with the English word gargle, and means “throat”. Gargoyles were originally intended as waterspouts and drains to keep rain water from running down the walls of buildings and damaging the foundations. Projecting out from the roof or parapet, they served to throw the water from the gutter clear.

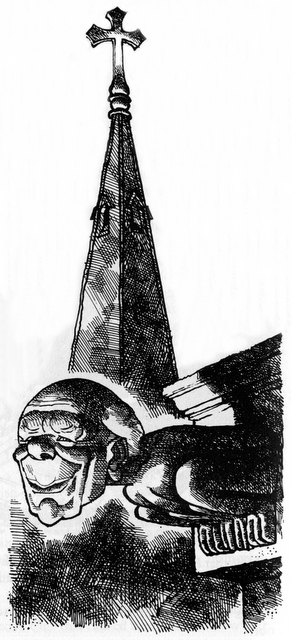

The adoption of Muggeridge as a modern gargoyle was not in stone, the work of a skilled stonemason, but in caricature, the work of the famous cartoonist, Wally Fawkes, better known as Trog. It is extraordinary that the depiction of Malcolm Muggeridge as a gargoyle in ink reached a vastly larger audience than would ever be achieved by one of stone. The depiction was very apt and appropriate given Muggeridge’s fascination with gargoyles and his desire to identify himself with them so frequently in his writing and broadcasts.

The adoption of Muggeridge as a modern gargoyle was not in stone, the work of a skilled stonemason, but in caricature, the work of the famous cartoonist, Wally Fawkes, better known as Trog. It is extraordinary that the depiction of Malcolm Muggeridge as a gargoyle in ink reached a vastly larger audience than would ever be achieved by one of stone. The depiction was very apt and appropriate given Muggeridge’s fascination with gargoyles and his desire to identify himself with them so frequently in his writing and broadcasts.

It remains to be seen whether a more permanent Muggeridge gargoyle is ever commissioned, carved in stone and affixed to a building for future generations to gaze at in awe and wonder. A Muggeridgean gargoyle could perhaps make an interesting addition to Broadcasting House, London, home of the BBC. He could look down with amusement and “told you so” resignation at the fine mess broadcasters get themselves into.

Perhaps his presence there is needed as a constant reminder of his prophesies and dire predictions. In “Christ and the Media”, now republished, he lamented the falling standards of taste and the departure of the BBC from maintaining and expounding Christian moral values.

Excerpted from David Williams’ “Les Gargouilles de Dijon” and “Gargoyles — a chip off the old block” editor of The Gargoyle publication of the Malcolm Muggeridge Society.

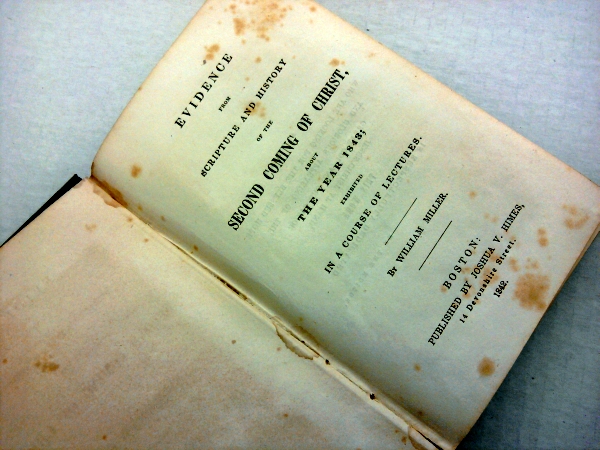

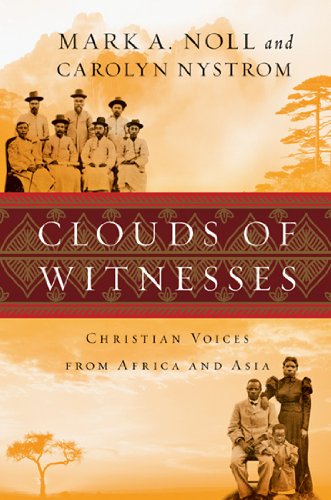

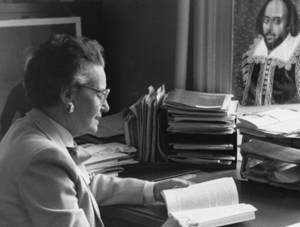

The Malcolm Muggeridge Papers are available to researchers at the Wheaton College Archives & Special Collections.