In early March 1965 half of Alabama’s population were black and only one percent of them registered to vote. Despite the Civil Rights Act of 1964 being signed eight months earlier by Lyndon Johnson, very little headway was made in dismantling the Jim Crow structures in areas of the South. In Alabama, particularly in Selma, efforts were made to quell the work of those seeking equality and civil rights. One week after the signing of the Civil Rights Act, Selma’s Judge James Hare forbade any gathering of three or more people to further civil rights work. The Dallas County Voters League called upon the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) to help them to call attention to the inequalities. The SCLC responded.

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference came to Selma in the early days of 1965 to begin working on voter’s rights. On February 18, 1965 Alabama State troopers clashed with civil rights workers and a trooper killed Jimmie Lee Jackson as he sought to protect his grandfather.  The first march, which took place on March 7, 1965, was called in response to this shooting and was planned to go to Montgomery to confront Governor George Wallace with the voting inequities and shooting. This initial march, later referred to as “Bloody Sunday,” gathered a crowd of 600 marchers who were brutally attacked. The march began quietly, but once marchers crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge state troopers began to beat marchers. Tear gas was also used and mounted troopers charged into those gathered, leaving many bloodied and injured with seventeen marchers hospitalized.

The first march, which took place on March 7, 1965, was called in response to this shooting and was planned to go to Montgomery to confront Governor George Wallace with the voting inequities and shooting. This initial march, later referred to as “Bloody Sunday,” gathered a crowd of 600 marchers who were brutally attacked. The march began quietly, but once marchers crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge state troopers began to beat marchers. Tear gas was also used and mounted troopers charged into those gathered, leaving many bloodied and injured with seventeen marchers hospitalized.

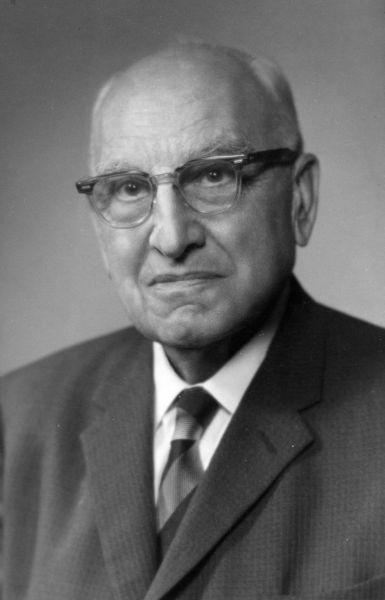

The news of the brutalization during the march was televised around the country and stirred many to action. Dr. Hudson Armerding was shocked at the police brutality and sent a telegram to Governor George Wallace.

URGE RECONSIDERATION OF USE OF FORCE IN DEALING WITH ORDERLY AND PEACEFUL NEGRO MARCHERS

This telegram was read in chapel held on Monday, March 8th. Robert Orth, in his entry in an online guest book for memories of Dr. Armerding after his passing in early December 2009, said that this action for justice made him proud. Others were also stirred to action. Wheaton College seniors Randy Baker and Bob Vischer left Wheaton that Monday afternoon and arrived in Selma the next morning before the 11 am meetings preparing for a second march. Vischer said he “could think of no better way to express my concern than through action” (Wheaton Record, March 18, 1965, p. 1).

The second march took place on March 9 with Martin Luther King, Jr. calling clergy and citizens from across the country to join him. Due to the violence of Bloody Sunday, efforts were made to try and prevent another outbreak of violence. The SCLC sought a court order that would prohibit the police from interfering. Unfortunately, the injunction was not granted, but, instead, Federal District Court Judge Frank Minis Johnson issued a restraining order that prevented the planned march. Despite the restraining order, 2,500 marchers began to walk toward the Edmund Pettus Bridge and were again met by a large line of troopers. After a short prayer session King encouraged the marchers to turn around. Though there was no violence at the march, that evening Rev. James Reeb and two other ministers in Selma for the march were beaten. Refused treatment in Selma for his injuries, Reeb was taken to Birmingham. Here he died two days later.

The second march took place on March 9 with Martin Luther King, Jr. calling clergy and citizens from across the country to join him. Due to the violence of Bloody Sunday, efforts were made to try and prevent another outbreak of violence. The SCLC sought a court order that would prohibit the police from interfering. Unfortunately, the injunction was not granted, but, instead, Federal District Court Judge Frank Minis Johnson issued a restraining order that prevented the planned march. Despite the restraining order, 2,500 marchers began to walk toward the Edmund Pettus Bridge and were again met by a large line of troopers. After a short prayer session King encouraged the marchers to turn around. Though there was no violence at the march, that evening Rev. James Reeb and two other ministers in Selma for the march were beaten. Refused treatment in Selma for his injuries, Reeb was taken to Birmingham. Here he died two days later.

While in Selma Baker and Vischer averted a violent clash as they were leaving town. As they walked in downtown Selma the two were confronted by four white men asking “where they were marching.” Baker was grabbed and hit. Extracting themselves they fled to their car. Vischer recalled the sense of fear he had in that moment and, with empathy, described the plight of blacks in Alabama.

A third march from Selma began with federal protection on March 21 and lasted five days, making it to Montgomery over 50 miles away. On August 6, 1965, the federal Voting Rights Act was passed. This brought a culmination to the efforts of King and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in Selma.

A week after the reporting of Dr. Armerding’s telegram and the Wheaton marchers in Selma, Bob Herron asked questions of himself and his fellow classmates through a Letter to the Editor, asking, “whether we are really working in some way to help those who are being treated so unjustly. In a shrinking world what happens in Alabama not only affects us, but the moral issues at stake demand that we seek justice. We cannot be content to affirm a creed and not realize the profound implications that are necessarily entailed.”