Twenty years ago, the Wheaton Alumni magazine began a series of articles in which Wheaton faculty told about their thinking, their research, or their favorite books and people. Professor of Communications and Director of Theater Jim Young (who taught at Wheaton from 1973-2005) was featured in the Summer 1995 issue.

“On My Mind,” she told me, “On My Mind.” I confess that I rather quickly thought of the song title, “Georgia on my Mind.” After all, it was Georgia Douglass, the editor of Wheaton Alumni, who had asked me to write this, and perhaps more significantly, my wife, June, is from Georgia. So, appropriately, Georgia is on my mind.

“On My Mind,” she told me, “On My Mind.” I confess that I rather quickly thought of the song title, “Georgia on my Mind.” After all, it was Georgia Douglass, the editor of Wheaton Alumni, who had asked me to write this, and perhaps more significantly, my wife, June, is from Georgia. So, appropriately, Georgia is on my mind.

But, of course, it didn’t take me long to realize that no other human being is on my mind in the same way that June is. But as I sat down in front of my precious friend, the Smith-Corona portable, newly-equipped with a grafted-on “t,” I breathed a prayer for this writing. I knew at once that the name of Jesus was the noun that “on my mind” modified.

What if we didn’t know his name? Names such as Savior, Teacher, Friend, Shepherd, as wonderful as they are, don’t equal the name of Jesus. The name that Scripture tells us is the only “name under heaven whereby we must be saved.” It is the name to which “every knee shall bow.”

There is a wonderful, blessed song we used to sing at camp meetings and at Sunday evening services. The prosody of the lyrics would be rejected by my professorial friends who teach creative writing, and the music, I suspect, would be lampooned by those in the Conservatory. Nevertheless the words are on my mind, and I want you to read them tolerantly:

Jesus is the sweetest name I know,

And He’s just the same

As His lovely name,

And that’s the reason why I love

Him so,

For Jesus is the sweetest name I know.

I’m embarrassed, but that song is on my mind. It blesses me a lot, even though I know the causal reasoning in the last two lines makes no sense. It just reflects what his name means to me.

Since I joined the Wheaton faculty in 1973, I have grown significantly and changed immensely. You might say I have gone through a major “p.t.,” or prepositional transition. Increasingly I have, through God’s grace and very slowly, moved from the “on” to an “in.” I am far from having completed the “p.t.” but through the writings of Thomas Merton, Alan Jones, and Henri Nouwen, and through the liturgy of the church at which I worship, I am creeping toward Paul’s invitation to “let this mind dwell in me.” There are times, far from frequent enough, when in prayer or worship, I know one of my convolution “file folders” is opened, emptied, and Jesus, Sweetest Name, enters in. Yet I am so far from living, moving, and having my being in him!

As I nudge in my Journey Into Christ (a great book by Alan Jones), I am beginning to experience at least two significant life changes. One is that my time with Jesus is far less “agendized.” It has become more intimate, and I no longer come to him with a list of my needs and go from him with a list of errands I then “sacrificially” perform. I sense more times with Jesus when I feel like the monk in the French monastery who often stayed after morning mass to sit in chapel. One day as he sat there, the abbot approached him and asked, “Why do you sit here when your brothers are in the garden, in the kitchen, in the library about their work? All you are doing is looking at the Crucifix.” The monk looked up and said, “Well, it’s just that I look at him, he looks at me, and we are happy together.” This reminds me of another one of those Sunday evening songs, “What a fellowship, what a joy divine, leaning on the everlasting arms.” The arms, the literal arms of Jesus are wondrous to behold, restoring to lean upon. Dwelling on the name of Jesus leads me toward that intimacy.

Another change as the mind of Jesus moves in, is that so much of what I sense Jesus meant by “the world” seems to pale into almost nothing. As his mind moves in, I find myself being called to (and by no means always answering) a smaller house, fewer clothes, a small car, a nurturing of our earth and conserving of its resources, to non-busyness, to a simpler lifestyle. So much of the “world” seems infinitely less alluring than the “joy divine” provided by the “sweetest name I know.” Try something with me. Have him in your mind. Breathe aloud the name of Jesus four times a day. See where the Holy Spirit takes the dialog.

Please know, all the Georgias and Georges of my life, that I write of what I long for and not what I have attained. I confess daily how far I am from having his mind. But what is retirement for if not to press on, to learn to DWELL in the secret place of the Most High?

———-

Dr. Young retires this year (1995) after having taught at Wheaton College for 23 years. In 1986-87 he was named senior professor of the year, Besides teaching high school for seven years, he taught at Asbury College, Taylor University, University of Wisconsin-Madison, and was chair of theater at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst. He has written numerous monographs and book reviews, including the monograph titled The Staging of the York Mystery Cycle for which he won the Golden Anniversary Award for Best Publication in Theater History. He also won the AMOCO Gold Medallion for leadership in the American College Theater Festival. He and his wife, June, live in Wheaton, and have two sons and daughters-in-law, Steve and Susan, and Mitch and Gail, and five grandchildren.

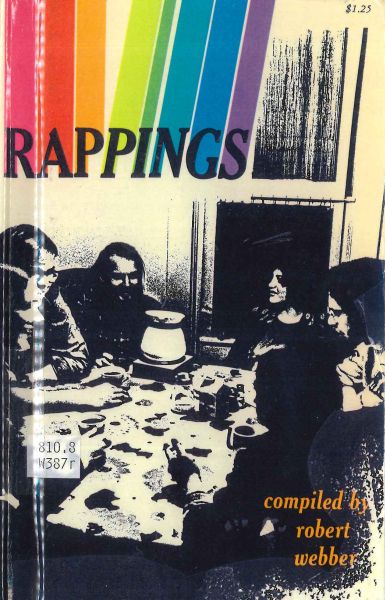

Dr. Robert Webber, former professor of theology at Wheaton College, expressed deep concern for Christian youth entering the 1970s, an era of tremendous political and sociological upheaval. In 1971 he published Rappings, a compilation of poems by Wheaton College students. He writes:

Dr. Robert Webber, former professor of theology at Wheaton College, expressed deep concern for Christian youth entering the 1970s, an era of tremendous political and sociological upheaval. In 1971 he published Rappings, a compilation of poems by Wheaton College students. He writes: