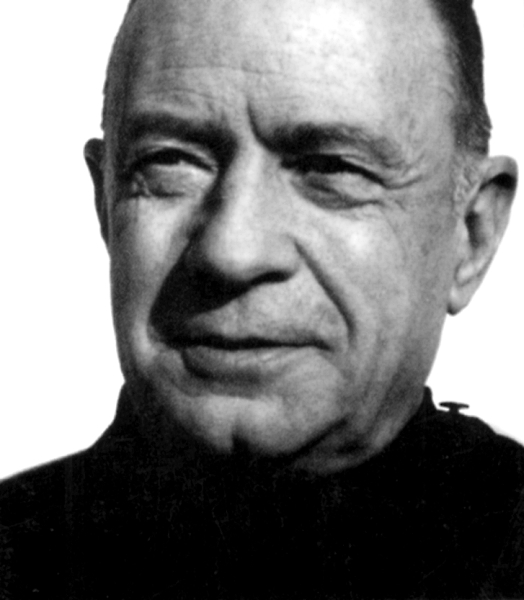

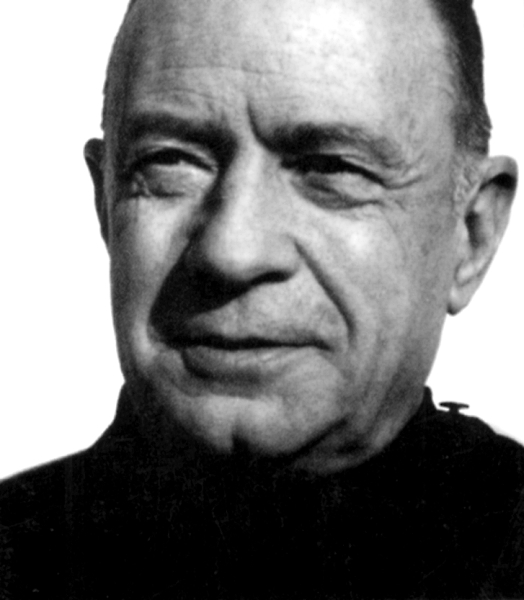

The Wheaton College Archives & Special Collections house the papers of noted sociologist and theologian Jacques Ellul. Though not all recognize the totality of Ellul’s ethics and writings, as the more secular fail to see the significance or importance of his theological writings, Ellul’s Christian works are key to understanding all of his other writings.

Ellul, born January 6, 1912 in Bordeaux, France, and grew up in a non-religious home. His mother was a devout Christian but in deference to Ellul’s father never discussed her faith with Ellul until after his own conversion. By his own description, his conversion was a violent one followed by years of struggling with his faith. After coming to peace with his faith and its call upon his life Ellul associated with the French Reformed Church, which he chose because it was weak and unorganized. Ellul always sought to side with the poor (in spirit, wealth, or other resources). Though he read Calvin it was Barth who appealed to Ellul. Another early influence upon Ellul’s Christianity was the Personalist Movement, which he helped found in France with Emmanuel Mounier. This movement stressed the reality, value and free will of persons. In conjunction with personalism, Immanuel Kant formed Ellul’s thoughts on the movement and Ellul claimed to have read the entire corpuses of Kant and Barth. Beside the poverty of his childhood, caused by his father’s unemployment, another influence upon Ellul was Karl Marx. Ellul believed that Marx accurately described the system under which Ellul’s world operated, but due to the influence of the Bible, and Jesus Christ as the hermeneutical key, he did not believe that Marx provided a suitable solution to the world’s ills.

Ellul, born January 6, 1912 in Bordeaux, France, and grew up in a non-religious home. His mother was a devout Christian but in deference to Ellul’s father never discussed her faith with Ellul until after his own conversion. By his own description, his conversion was a violent one followed by years of struggling with his faith. After coming to peace with his faith and its call upon his life Ellul associated with the French Reformed Church, which he chose because it was weak and unorganized. Ellul always sought to side with the poor (in spirit, wealth, or other resources). Though he read Calvin it was Barth who appealed to Ellul. Another early influence upon Ellul’s Christianity was the Personalist Movement, which he helped found in France with Emmanuel Mounier. This movement stressed the reality, value and free will of persons. In conjunction with personalism, Immanuel Kant formed Ellul’s thoughts on the movement and Ellul claimed to have read the entire corpuses of Kant and Barth. Beside the poverty of his childhood, caused by his father’s unemployment, another influence upon Ellul was Karl Marx. Ellul believed that Marx accurately described the system under which Ellul’s world operated, but due to the influence of the Bible, and Jesus Christ as the hermeneutical key, he did not believe that Marx provided a suitable solution to the world’s ills.

Ellul’s most important work is considered to be The Technological Society (in French: La Technique, 1954). Other important writings are Propaganda (Propagandes, 1962) and The Political Illusion (L’Illusion politique, 1964). His works sought to provide readers with the ability to critique how they engage the modern world. One of the most significant critiques of our time, especially from a Christian perspective, would be upon the “cult of efficiency” that permeates our culture. It is Ellul’s more explicitly theological writings, the ones that round out the pictures provided in the more sociological titles listed above, such as The Meaning of the City, The Politics of God and the Politics of Man and The Presence of the Kingdom, which challenge the practices of our culture. We live in a culture that emphasizes efficiency and demands it from every task. However the Gospel is inefficient.

Our culture is concerned with its technological advances and our lives are measured by what we possess. The accessories of our lives speak volumes about what we and others find important as they speak to our wealth, freedom and ability to acquire resources easily. The history of civilizations tells of their wealth and might, even of the strength of its armies and the technology of warfare. However the history of God’s dealings with humanity — his acts of grace and mercy towards his creation — tell of a bulrush baby being rescued and furnace-cast followers being saved. God has a heavenly host at his command, yet he seeks and uses the weak and powerless. We see this in the story of Gideon who was from the smallest family in the weakest clan (Judges 6). Solomon extolled the Lord for his care for the weak and needy (Psalm 72). Ezekiel records the words of the Lord and tells us that God retrieves the strays, strengthens the weak and destroys the strong (Ezekiel 34). The Gospel is intertwined with these principles to the point that Paul revels in his own weaknesses (II Corinthians 12) as they serve as conduits of God’s grace.

Decades ago the writings of Jacques Ellul ominously reveal the problems of our efficient age. In his Technological Society Ellul clearly outlines the trajectory of society and what is so portentous is that he penned these words more than fifty years ago and we are still on that same trajectory and seeing the terminus out in front of us; the outcome that Ellul portrays is not inviting. In very rational fashion he articulates the logical conclusions of the choices humanity has made. He calls his readers to ask questions, like “what will this create?” prior to embarking upon a course of action or implementing a new process/technology.

Ellul died May 19, 1994 leaving a theological legacy that can be found in more than fifty books in French that were translated into English and eight other languages.

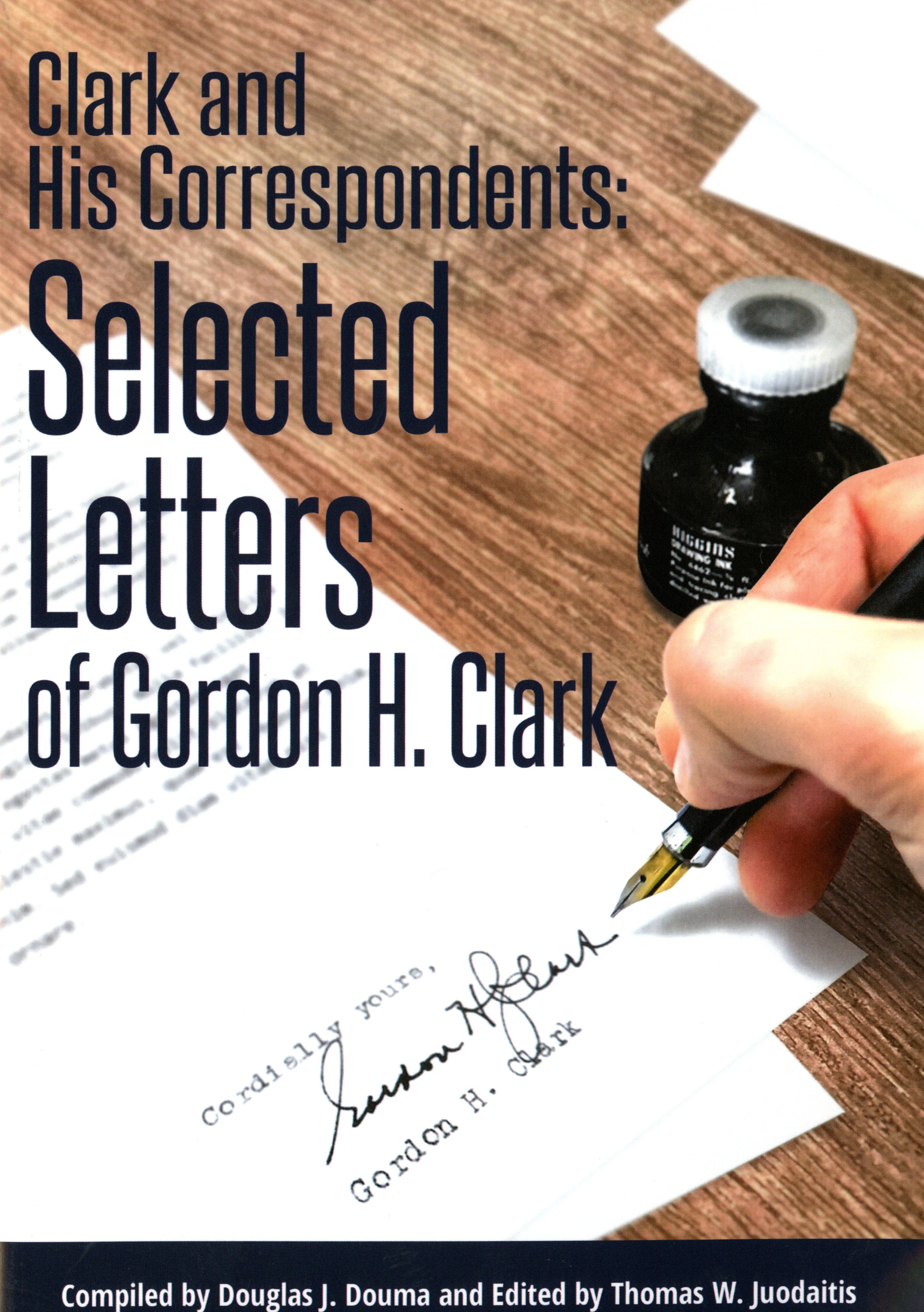

Compiled by Douglas J. Douma and edited by Thomas W. Juodatis, Clark and His Correspondents: Selected Letters of Gordon H. Clark (2017) presents an array of Clark’s exchanges with such prominent evangelical and fundamentalist leaders as J. Oliver Buswell, V. Raymond Edman, E.J. Carnell, Cornelius Van Til, Carl F.H. Henry and J. Gresham Machen. The compilation uses many letters scanned from the College Archives of Buswell Library.

Compiled by Douglas J. Douma and edited by Thomas W. Juodatis, Clark and His Correspondents: Selected Letters of Gordon H. Clark (2017) presents an array of Clark’s exchanges with such prominent evangelical and fundamentalist leaders as J. Oliver Buswell, V. Raymond Edman, E.J. Carnell, Cornelius Van Til, Carl F.H. Henry and J. Gresham Machen. The compilation uses many letters scanned from the College Archives of Buswell Library.

On October 30, 1997

On October 30, 1997