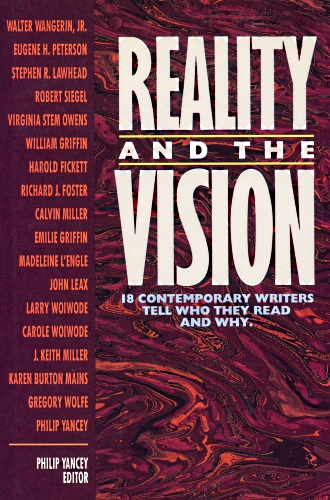

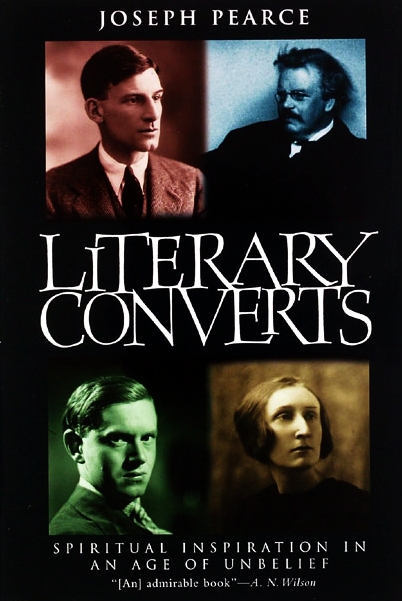

Joseph Pearce, in his Literary Converts, presents biographical explorations into the spiritual lives of some of the greatest writers in the English language and includes Malcolm Muggeridge and T.S. Eliot among his subjects. This book touches on some of the most important questions of the 20th century.

Joseph Pearce, in his Literary Converts, presents biographical explorations into the spiritual lives of some of the greatest writers in the English language and includes Malcolm Muggeridge and T.S. Eliot among his subjects. This book touches on some of the most important questions of the 20th century.

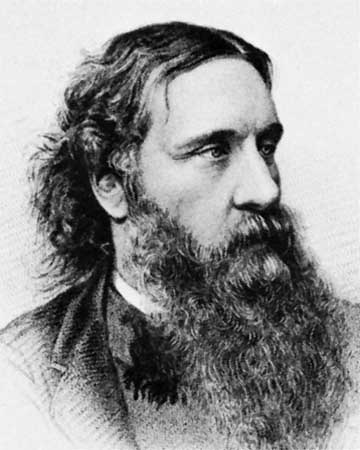

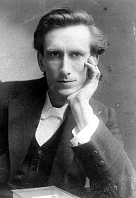

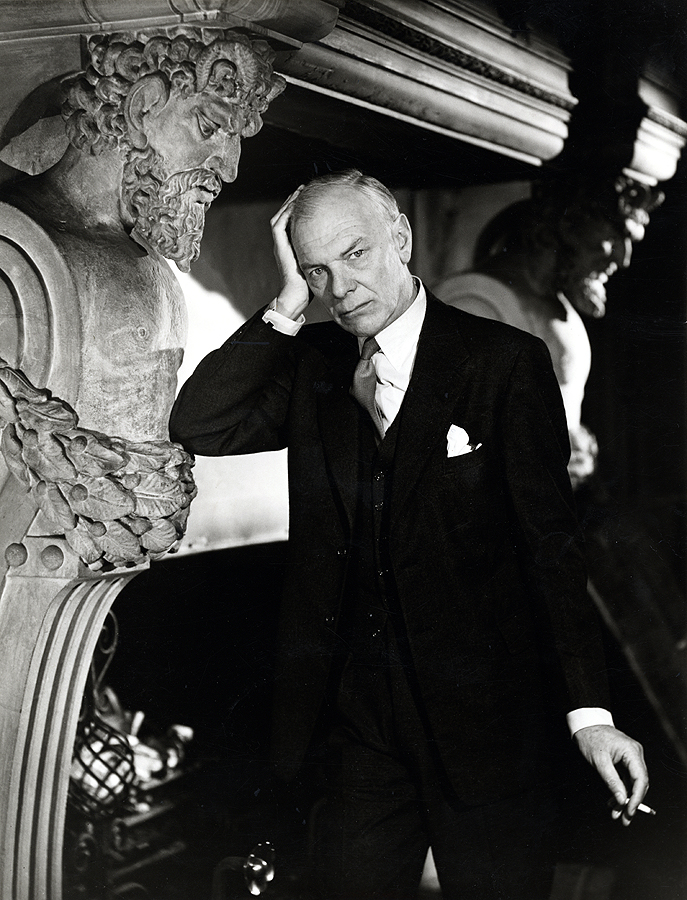

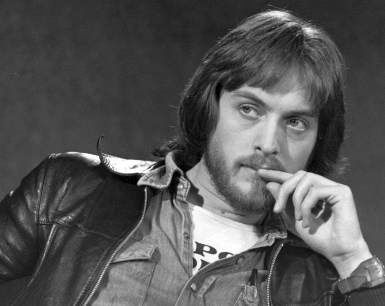

Malcolm Muggeridge seemed to have a ambivilent relationship with T.S. Eliot. Ian Hunter, in his biography Muggeridge: a life, indicates that Muggeridge had sent Eliot some of his short stories that Eliot praised. However, Muggeridge is also noted elsewhere that Eliot was a “death rattle in the throat of a dying civilization.” Muggeridge had been introduced to Eliot’s work while teaching in Cairo.

In The Chronicles of Wasted Time: The Green Stick, Muggeridge wrote that during “the thirties and the war years, I occasionally ran into Eliot at the Garrick Club; he was extremely amiable and polite, but, as it seemed to me, a man who was somehow blighted, dead, extinct. I wrote of him once that he was a death-rattle in the throat of a dying civilisation, for which a contributor to The Times Literary Supplement took me severely to task. Yet that was how I saw him–actually, several cadavers fitting into one another like Russian dolls. A New England one, an Old England one, a Western Values one. And so on.”

Muggeridge first heard of Eliot, particularly his Wasteland, while teaching in Egypt and attending a lecture by his department chair, Bonamy Dobree. In this lecture Dobree stated that “he would stake his literary reputation that the publication of Eliot’s ‘The Waste Land’ would be considered as being on a par with that of the Lyrical Ballads [by Wordsworth]. This was a statement that Muggeridge wished to refute on the spot, believing that it was unkind to let such a dramatic challenge pass unnoticed.

Patrick Walsh, in his reminicenses of Muggeridge in Modern Age, recounted a visit in 1988 where he noted that Muggeridge and Eliot had a similar spiritual journey through the wasteland of the twentieth-century and had “found peace at the ‘intersection of the timeless with time.'” He read to Muggeridge from Eliot’s Thoughts After Lambeth, which [Muggeridge] was much taken with:

“The world is trying the experiment of attempting to form a civilized but non-Christian mentality. The experiment will fail; but we must be very patient in awaiting its collapse; meanwhile redeeming the time: so that the Faith may be preserved alive through the dark ages before us; to renew and rebuild civilization and save the world from suicide.”

Walsh noted that both Muggeridge and Eliot were twentieth-century pilgrims–both re-learning Christianity for themselves. They found they could not rescue their age, but could rescue their own souls through time for eternity. “They both came to love the beauty of the world and to look beyond it for consolation.”