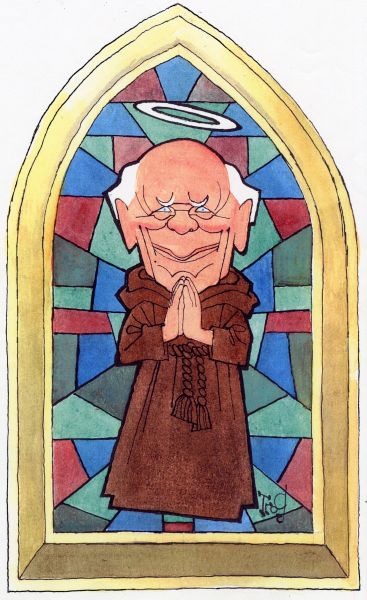

Evidently, no one asked Malcolm Muggeridge what he would do were he suddenly elevated to the papal throne; nonetheless, the indomitable journalist, not even Catholic at the time, offers his fantasies on the prospect. “If I Were Pope…” appeared in The National Review, June 9, 1978, the so-called “year of three popes,” during which Pope Paul VI died, Pope John Paul I was elected and reigned for one month before dying, and Pope John Paul II was elected to an influential 27-year papacy. As Pope Francis begins his pontificate after the resignation of Pope Benedict XVI, perhaps it is appropriate to revive Muggeridge’s conservative ruminations on a few ecclesiastical matters.

Evidently, no one asked Malcolm Muggeridge what he would do were he suddenly elevated to the papal throne; nonetheless, the indomitable journalist, not even Catholic at the time, offers his fantasies on the prospect. “If I Were Pope…” appeared in The National Review, June 9, 1978, the so-called “year of three popes,” during which Pope Paul VI died, Pope John Paul I was elected and reigned for one month before dying, and Pope John Paul II was elected to an influential 27-year papacy. As Pope Francis begins his pontificate after the resignation of Pope Benedict XVI, perhaps it is appropriate to revive Muggeridge’s conservative ruminations on a few ecclesiastical matters.

Summarizing his points:

1) Locating a private, quiet retreat, perhaps Castel Gondolfo, Pope Malcolm would “…meditate upon the Church’s extraordinary survival through the twenty centuries of Christendom despite every sort of abomination committed by, or under the auspices of, my predecessors…”

2) Considering the ramifications of Vatican II, he would “…meditate upon the Church’s present circumstances, so full of confusion, strife and lunacy following Pope John’s Vatican Council and the amazing decision resulting therefrom to have another Reformation, just when the former one – Luther’s – seemed finally to have run into the sand.”

3) Not embracing complete isolation, he would “…have Mother Teresa and some of her Sisters of Charity with me at my retreat, her cooperation having been a precondition of my accepting the pontifical appointment in the first place…Her extraordinary influence and clarification are conveyed, not so much by words or exhortation, as by the love she radiates, shining out from her visibly, like light.”

4) Leaving the serenity of his retreat to address a troubled society, he would “…reissue Humanae Vitae in a greatly simplified form, reinforcing its essential point than any form of artificial contraception is inimical to the Christian life.”

5) Next, “…I should suspend the prohibition of the Tridentine Mass and the traditional Latin liturgy, which would henceforth be permissible whenever and wherever there was an appreciable demand for it. The disco-style vernacular worship, with its sadly banal words, which has come to take the place of the traditional liturgy would be allowed to go on, but I should secretly hope that, as fashions changed, it might wither away.”

6) Muggeridge would tighten the noose in other ways, as well. “Imagining myself sitting in the Vatican, or strolling up and down the Vatican garden, I feel sure I should be assailed by the temptation to do a bit of excommunication and anathema on my own account as and when the opportunity presented itself. Freedom-fighting prelates, liberated nuns, Marxist-dialoguing Jesuits, and other such ribald clerical phenomena of our time, along with the accompanying literature, would be, for me, tempting targets.”

7) Thus empowered, he would also “….prepare the way for an underground Church to go on functioning when the open one has been either forcibly disbanded, or so corrupted and disoriented from within that it can no longer fulfill its traditional role…What I have in mind would be a Christian maquis or clandestine Catacombs Order, whose superior and members would be chosen with the utmost care for their abiding faith, mystical insight and love for the Church and its orthodoxy.”

“That would be a papacy indeed!” he concludes. “Perhaps – who can tell? – some unexpected papabile is even now being divinely groomed to take it on.”

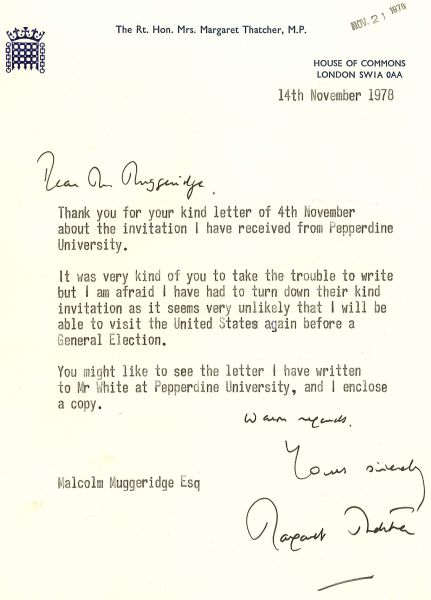

Muggeridge joined the Catholic Church in 1982. He died in 1990. His papers (SC-04), comprising manuscripts, correspondence, videos and memorabilia, are archived at Wheaton College Special Collections in Wheaton, IL.

But when William Leslie left his position in 1961 as assistant pastor of Moody Church, serving under Dr. Alan Redpath, to lead the struggling assembly, the district was severely blighted, collapsing beneath the weight of decrepitude, poverty and racial tensions. Leslie, a graduate of Wheaton College, realized that he must not only preach to touch the spirit, but he must also address the material welfare of his parish.

But when William Leslie left his position in 1961 as assistant pastor of Moody Church, serving under Dr. Alan Redpath, to lead the struggling assembly, the district was severely blighted, collapsing beneath the weight of decrepitude, poverty and racial tensions. Leslie, a graduate of Wheaton College, realized that he must not only preach to touch the spirit, but he must also address the material welfare of his parish.