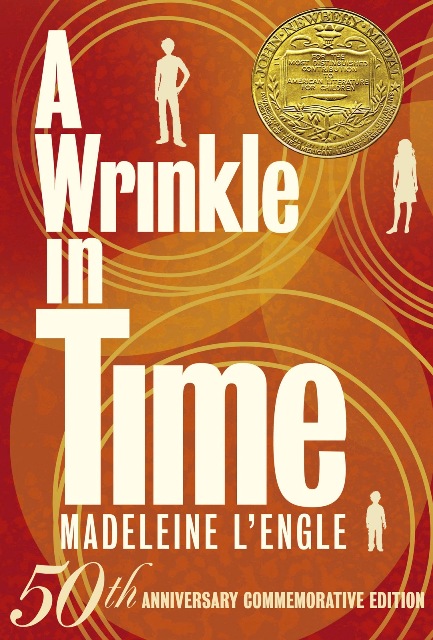

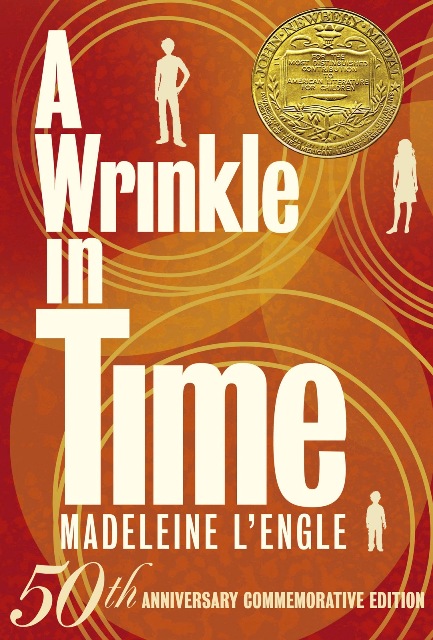

In celebration of the 50th anniversary of “A Wrinkle in Time”, this Newbery Award-winning novel written by Madeleine L’Engle has over 10 million copies in print. The following article was written by the author at the novel’s 25th anniversary.

It’s been twenty-five years since the publication of A Wrinkle in Time, and longer than that since I wrote it, and it is hard to believe that more than a quarter of a century has passed.

It’s been twenty-five years since the publication of A Wrinkle in Time, and longer than that since I wrote it, and it is hard to believe that more than a quarter of a century has passed.

When I wrote Wrinkle, I was in a state of transition. We had been living in northwest Connecticut for nearly a decade, and were ready to move back to New York City. When we left the frustrations and stresses of Manhattan and decided to raise our family in the protected environment of a small, dairy-farm village where there we more cows than people, my husband thought he had left the theater forever. But forever (to my joy) was over, and Hugh was going back to the theater, and this move was going to be what is now called “culture shock” for our children. So we bought a tent and five sleeping bags and set off on a cross-continent camping trip.

As we crossed the North American continent I continued the thinking that had begun a few months earlier when I had stumbled across a book of Einstein’s and discovered that for me higher math is easier than lower math. My background in science was nil, and in any case the new sciences that excited me weren’t being taught when I was in school and college.

There’s nothing like marriage, children, leaving home (I was born in Manhattan) to start one asking all the old questions: What does life mean? Does it matter? What is the universe like? Is there a pattern and a plan? And am I a part of it?

The old philosophies left me unsatisfied. The religious establishment made the mistake of answering the great questions to which there are no answers, only new questions. I would walk the dogs at night, looking at the incredible sweep of stars above me, and philosophies and theologies centered only on his planet, and usually on only a small segment of the population, seemed totally inadequate. They left me hungry for something more marvelous.

We left on our cross-country trip in the early spring of 1959 and the first idea for Wrinkle came to me as we were driving across the Painted Desert. The names Mrs. Whatsit, Mrs. Who and Mrs. Which simply popped into my head. I turned around in the car and said, “Hey, kids, I’ve just thought of three great names, Mrs. Whatsit, Mrs. Who and Mrs. Which. I’ll have to write a book about them sometime.” And so the names of the three cosmic bag ladies went into the subconscious creative slow cooker. In the evenings, in the tent, I read from the box of books I had brought with me: more Einstein; Planck, and his quantum theory; books on the macrocosmic world of astrophysics; books on the microcosmic world of particle physics. There I found ideas about the nature of being which stimulated and fascinated me. When we got home, my husband went right into a play, and I sat down at the desk and typed out, “It was a dark and stormy night,” and the book poured out of my fingers. Evenings, I would read to my children what I had written during the day, and they would say, “Oh, Mother, go back to the typewriter!” (They didn’t always say that.)

When I finished the manuscript, I was drained and excited. I believed it to be not only totally different from my six previously published books but by far the best thing I had ever written. My children loved it; my husband loved it; my agent loved it. I hope that its publication would end a decade during which I had received countless rejection slips for more traditional books, half a dozen of which are still in typescript upon my shelves.

Well, I was kept hanging for two years, by many different publishers.

“What is it?” I would be asked. “Is it fantasy or science fiction?”

“It’s a book.”

“But who is it for? Is it for children, or adults?”

Over and over again, I received nothing more than the formal, printed rejection slip. These cold, impersonal rejections hurt. I began to doubt myself. Didn’t any of what I saw in the book get onto the typewritten page?

I had written Wrinkle beginning in the late summer of 1959 and finished in early 1960. The world was still in chaos. While my husband was reestablishing himself in the theater, the children and I stayed in the country. War with Russia seemed imminent. At school, the children were taught to crouch under their little wooden desks, their hands over their heads, in case an atom bomb fell on the school. What insanity! Some of my feelings about this insanity are expressed in Wrinkle. In it, I was trying to write about my own questions, my own affirmation of meaning despite seeming chaos.

(After Wrinkle was published, I was frequently asked if Camazotz didn’t represent Soviet Russia. Interesting: nobody asks that anymore.)

We moved back to New York, which no longer seemed more insane than the rest of the world. Air-raid sirens going off every day at noon, signs for air-raid shelters, for closed highways “in case of enemy attack,” seemed no more realistic than crouching under a desk.

And the rejection slips continued. How could they seem important against a background of a planet gone mad? They did. My book was a candle in the dark for me, and a hope.

A form rejection slip came on the Monday before Christmas 1961. I was sitting on the bed, wrapping Christmas presents and trying to feel brave, and thinking I was succeeding. After Christmas, I discovered that I had sent a necktie to a three-year-old girl and a bottle of perfume to a bachelor uncle. I called my agent. “Send it back. It’s too different. Nobody’s going to publish it. It’s too hard on my family. Every time it’s rejected, I bleed all over the living room rug.”

He sent it back, and that ought to have been the end of it. But my mother was with us for Christmas, and I gave a party for some of her old New York friends, and one of them happened to belong to a small writing group led by John Farrar, co-founder of Farrar, Straus and Company. She insisted that I meet him. I was, at that moment, not particularly interested in meeting any publisher. But she set up an appointment, and I took the subway down to Union Square, bearing my very battered manuscript.

John had already read my first novel, The Small Rain, and had admired it. I told him that Wrinkle was very different, but he was eager to read it. In two weeks I heard from my agent that he had read it, and really liked it, but was afraid of it. My heart sank. I had been so hopeful, after leaving John’s office, that the long wait might be at an end.

John and Hal Vursell (who was to be my editor from then on until his death) sent the worn manuscript to a librarian for assessment. She wrote back, “I think this is the worst book I have ever read. It reminds me of The Wizard of Oz.”

I’m not sure how many more weeks it was before John called me to tell me that he was going to publish the book. I went back downtown to have lunch with him and Hal, and they warned me, “Now, dear, we don’t want you to be disappointed, but this book is not going to sell. It’s much too difficult for children. We’re publishing it as a self-indulgence because we love it, and we don’t want you to be hurt.”

And then, in the spring of 1962, A Wrinkle in Time was published, and it took off like a skyrocket.

The problem wasn’t that it was too difficult for children. It was too difficult for adults.

———-

The Papers of Madeleine L’Engle are housed in the Wheaton College Archives & Special Collections and are available for research.

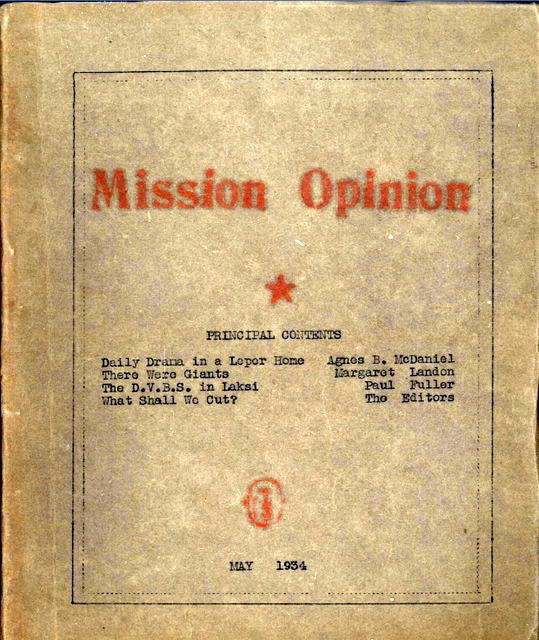

Mission Opinion was a controversial publication edited and published by Kenneth and Margaret Landon in 1934 and 1935, from their missionary post at Trang, Siam. It was a strictly in-house magazine for the missionaries of the Presbyterian Mission, with which the Landons served at the time. Its aim was to facilitate “expressions of opinion by members of the Siam Mission on matters relating to the policies and practices of the Mission.”

Mission Opinion was a controversial publication edited and published by Kenneth and Margaret Landon in 1934 and 1935, from their missionary post at Trang, Siam. It was a strictly in-house magazine for the missionaries of the Presbyterian Mission, with which the Landons served at the time. Its aim was to facilitate “expressions of opinion by members of the Siam Mission on matters relating to the policies and practices of the Mission.”