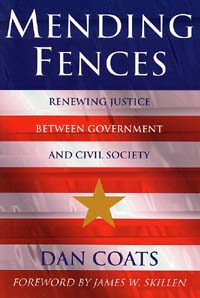

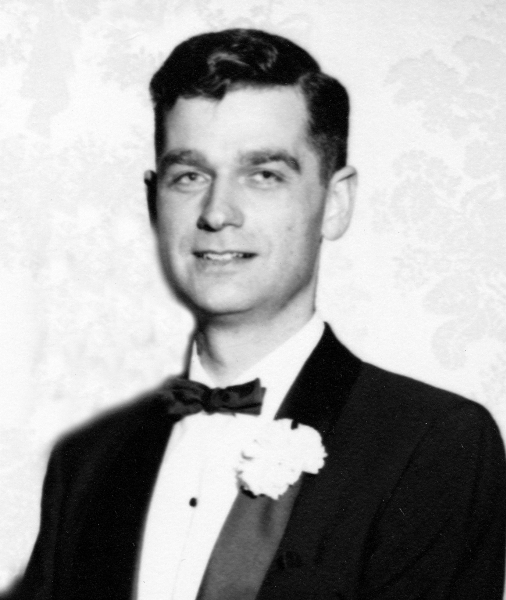

On October 30, 1997 Senator Dan Coats (R-IN) gave the third annual Kuyper Lecture entitled “Mending Fences: Renewing Justice Between Government and Civil Society,” sponsored by the Center for Public Justice and Wheaton College. During the economic prosperity of the late 1990s, Coats asked whether a growing economy, high employment, and low interest rates indicate that the citizens of the United States are thriving? In Coats’ published address and responses from three distinguished social activists, Coats applauded America’s economic prosperity and the more limited role of government, but was distressed by the moral crisis of the culture and the signs of a weakening “civil society.” There is a paradox inherent in the viewpoint of the American founders: In order to have political freedom, individuals must embody self-discipline and virtue. It is the responsibility of parents, church leaders, and nonprofit service providers to train each generation in democratic habits and manners: reasoned reflection, self-mastery, public spirit, and respect for the rights of others. Senator Coats addressed the need to strengthen the authority and economic well-being of those institutions that teach moral values. As author of the legislative package The Project for American Renewal, he argued that the government must use its authority to empower constructive actions in the nongovernmental sector. [ Excerpted from The Center for Public Justice ].

On October 30, 1997 Senator Dan Coats (R-IN) gave the third annual Kuyper Lecture entitled “Mending Fences: Renewing Justice Between Government and Civil Society,” sponsored by the Center for Public Justice and Wheaton College. During the economic prosperity of the late 1990s, Coats asked whether a growing economy, high employment, and low interest rates indicate that the citizens of the United States are thriving? In Coats’ published address and responses from three distinguished social activists, Coats applauded America’s economic prosperity and the more limited role of government, but was distressed by the moral crisis of the culture and the signs of a weakening “civil society.” There is a paradox inherent in the viewpoint of the American founders: In order to have political freedom, individuals must embody self-discipline and virtue. It is the responsibility of parents, church leaders, and nonprofit service providers to train each generation in democratic habits and manners: reasoned reflection, self-mastery, public spirit, and respect for the rights of others. Senator Coats addressed the need to strengthen the authority and economic well-being of those institutions that teach moral values. As author of the legislative package The Project for American Renewal, he argued that the government must use its authority to empower constructive actions in the nongovernmental sector. [ Excerpted from The Center for Public Justice ].

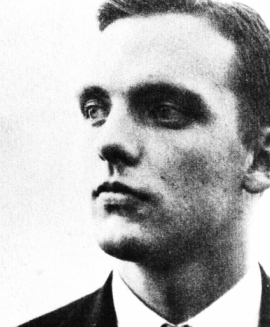

The annual Kuyper lecture has been held since 1995 and is named for Abraham Kuyper (1837-1920), an influential Dutch scholar-statesman. Kuyper saw that religion was a the deep, driving influence of competing religions in human society and that Jesus Christ made comprehensive and inescapable claims on the world and these two were exemplified with the strength and influence of international bonds of Christian community. Kuyper believed that the Christian life cannot be confined to church life. Accepting Christ’s claim of authority over the entire world, he sought to follow the implications of that faith into politics, journalism, education, and other human endeavors.

The Daniel R. Coats Papers are available to researchers at the Wheaton College Archives & Special Collections.

![]() LISTEN to Dan Coats 1997 Kuyper lecture (mp3 – 01:04:08, Coats begins at 11:10)

LISTEN to Dan Coats 1997 Kuyper lecture (mp3 – 01:04:08, Coats begins at 11:10)

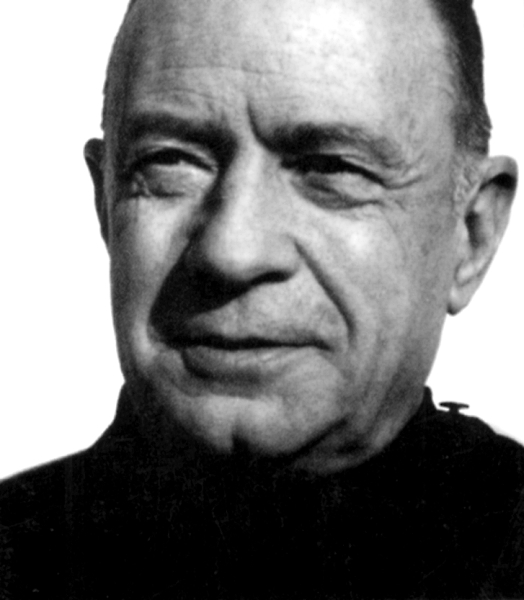

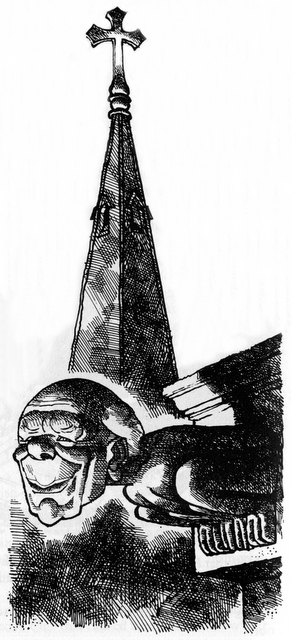

The adoption of Muggeridge as a modern gargoyle was not in stone, the work of a skilled stonemason, but in caricature, the work of the famous cartoonist, Wally Fawkes, better known as Trog. It is extraordinary that the depiction of Malcolm Muggeridge as a gargoyle in ink reached a vastly larger audience than would ever be achieved by one of stone. The depiction was very apt and appropriate given Muggeridge’s fascination with gargoyles and his desire to identify himself with them so frequently in his writing and broadcasts.

The adoption of Muggeridge as a modern gargoyle was not in stone, the work of a skilled stonemason, but in caricature, the work of the famous cartoonist, Wally Fawkes, better known as Trog. It is extraordinary that the depiction of Malcolm Muggeridge as a gargoyle in ink reached a vastly larger audience than would ever be achieved by one of stone. The depiction was very apt and appropriate given Muggeridge’s fascination with gargoyles and his desire to identify himself with them so frequently in his writing and broadcasts.