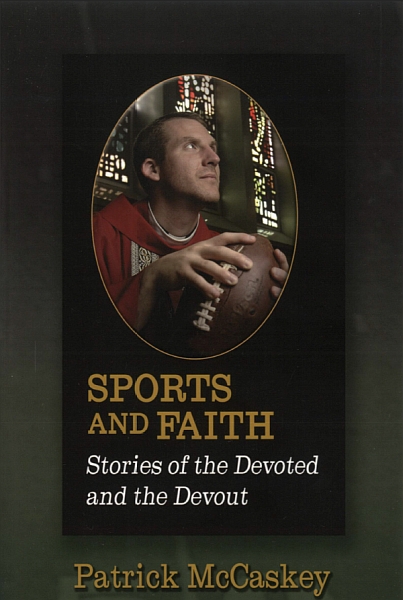

The Apostle Paul used athletic allusions to communicate the role of the Christian in the world. He used athletic metaphors to describe the Christian life. In his new book, Sports and Faith (Sporting Chance Press, 2011), Pat McCaskey, Senior Director of the Chicago Bears, through a personal memoir looks at the lives of numerous individuals he encountered who had sought to be faithful and to make a difference in the lives of others. McCaskey looks at his grandfather, George Halas, “Red” Grange, Brian Piccolo, the Nancy Swider-Peltzs, Wayne Gordon and John Perkins. Some of the names may more readily pop into one’s mind and memory, but the individuals represented are examples worthy of attention with lessons to tell. Mr. McCaskey’s wife, Gretchen, and son, Edward, are graduates of Wheaton College (1974 and 2009 respectively).

The Apostle Paul used athletic allusions to communicate the role of the Christian in the world. He used athletic metaphors to describe the Christian life. In his new book, Sports and Faith (Sporting Chance Press, 2011), Pat McCaskey, Senior Director of the Chicago Bears, through a personal memoir looks at the lives of numerous individuals he encountered who had sought to be faithful and to make a difference in the lives of others. McCaskey looks at his grandfather, George Halas, “Red” Grange, Brian Piccolo, the Nancy Swider-Peltzs, Wayne Gordon and John Perkins. Some of the names may more readily pop into one’s mind and memory, but the individuals represented are examples worthy of attention with lessons to tell. Mr. McCaskey’s wife, Gretchen, and son, Edward, are graduates of Wheaton College (1974 and 2009 respectively).

Category Archives: Special Collections

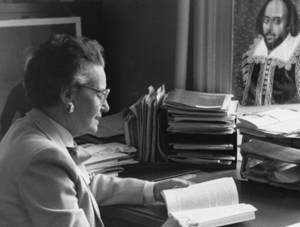

On My Mind – Beatrice Batson

Twenty years ago, the Wheaton Alumni magazine began a series of articles in which Wheaton faculty told about their thinking, their research, or their favorite books and people. Professor of English Emeritus E. Beatrice Batson (who taught at Wheaton from 1957-1987) was featured in the August/September 1991 issue.

When I came to teach at Wheaton in the autumn of 1957, I discovered a nucleus of professors and students charged with excitement over Wheaton’s mission as a Christian liberal arts college. Combined with this concern was the belief that mind and spirit should he so constantly and consistently nurtured that complacency would be highly unlikely to make permanent inroads. I found the atmosphere extraordinarily exhilarating. Admittedly, some of us were idealists; perhaps such idealists that not a few individuals determined to find new and different ways of talking about the whole educational process. Through the decades, however, there were still those who were unable to think dispassionately of Wheaton’s mission. Similar zeal is by no means absent in 1991.

When I came to teach at Wheaton in the autumn of 1957, I discovered a nucleus of professors and students charged with excitement over Wheaton’s mission as a Christian liberal arts college. Combined with this concern was the belief that mind and spirit should he so constantly and consistently nurtured that complacency would be highly unlikely to make permanent inroads. I found the atmosphere extraordinarily exhilarating. Admittedly, some of us were idealists; perhaps such idealists that not a few individuals determined to find new and different ways of talking about the whole educational process. Through the decades, however, there were still those who were unable to think dispassionately of Wheaton’s mission. Similar zeal is by no means absent in 1991.

Several years following that autumn of 1957, I met at a professional conference one of my former students, then an advanced graduate student at Yale. Among the first questions he asked me were: ‘What are Wheaton students really like now?” and “Is the faculty remembering the mission of the College?” Or in paraphrase, “Are faculty members consciously aware that they are teaching human beings who must make moral and spiritual responses in life ?”

My reply to him was another question: “What kind of student do you wish to see at Wheaton?” Quick as a flash, he answered, “Hungry students. Let them he cynical, and let them be angry.” He continued, “But whatever they are, be sure they are hungry–hungry for nourishment that feeds mind, heart, and spirit.” What came clear was that somebody had a heavy and joyous responsibility. “To study at a college like Wheaton,” he insisted, “is to he exposed to a faculty and a curriculum that will not let students forget the large human questions of meaning and purpose.” However excellent the speakers at that professional conference may have been, it was the urgent tone of my former student’s pleas that lingered longest in my memory.

With the onslaught of unparalleled campus unrest in many colleges and universities during the late sixties and early seventies, prophets of doom began to declare that the liberal arts ideal would wither away or bit by bit literally slip from consideration in the strongest liberal arts colleges. Problems were far too complex, we were frequently told, for contemporary students to spend time on “the arcane vestiges of the past,” as critics pejoratively titled the liberal arts. To jettison every thinker and artist prior to the late twentieth century seemed no solution to some of us. Minds and imaginations burnished on Plato and Aristotle, Aeschylus and Shakespeare, Augustine and Kierkegaard (and scores of others) might well be the sort of informal minds and lively imaginations that should be working on different issues, we reasoned. Besides, students hungered for meaning and purpose.

What my former student urged still persisted in my mind in more recent years when numerous educational leaders held that students were in college to acquire a passport to immediate pleasure, instant success, and economic affluence. This indictment, however, failed to dissuade some of us from our firm belief in the mission of a Christian liberal arts college.

When I left close contact with the thinking of students and faculty for retirement in 1988, I continued to teach one course in Shakespeare. Although I was aware of new theories that pervaded scholarly writing and knew of the abuse that pseudo-scholars heaped upon those who affirmed the liberal arts ideal, I continued to discover that students did not consider Shakespeare’s works to be anachronisms. They perceived that his inimitable writings embodied large human questions and always-contemporary subjects even though the great artist wrote 400 years before they were horn.

In October 1990, I came from active retirement to serve as Kilby Professor of English and from October to May as acting chair, due to the serious illness of my colleague, Dr. Joe McClatchey. In these responsibilities, I had a closer contact with students and more interaction with faculty.

Since that autumn in 1957, many changes have occurred. In this year, 1990-91, faculty were challenging luminaries on their own ground, discussing terms not even named in 1957; students were wrestling with new issues, thinking hard on complexities born of their technological age. As before, there was still a nucleus who saw themselves as “privileged inheritors of a rich legacy” the mission of the Christian liberal arts college. I have a deep conviction, even in my most pessimistic moments, that Wheaton has in its community particular individuals who know that they are “custodians of something immensely valuable,” and they sense a dire need to keep it alive.

———-

Dr. E. Beatrice Batson, Professor Emerita of English, was chair of the department for 13 years. During the academic year 1990-91, she served as Kilby Professor of English and as acting chair. Since her retirement she continues her work as coordinator of the Shakespeare Collection and has organized bi-annual institutes for undergraduate teachers of Shakespeare, sponsored by the Shakespeare Special Collection, since 1992. She received the Wheaton College Alumni Association Distinguished Service to Alma Mater Award in 2007.

Books Without End

For various reasons books occasionally do not make it into a reader’s hands; and so the book that might-have-been acquires a sort of mystique. “A lost book,” writes Stuart Kelly in The Book of Lost Books: An Incomplete History of All the Great Books You’ll Never Read (2005), “is susceptible to a degree of wish fulfillment. The lost book, like the person you never dared asked to the dance, becomes infinitely more alluring simply because it can be perfect only in the imagination.” The simplest form of loss, notes Kelly, is destruction. An infamous example is the legendary Library of Alexandria, supposedly holding all the wisdom of the ancient world, burning to ashes in a single night. Other books are sacrificed to carelessness, as when a certain publisher moved offices, absentmindedly leaving behind manuscripts in a building slated for immediate demolition. Some books never achieve completion because of the death of the author, as when Charles Dickens expired before solving The Mystery of Edwin Drood, or Geoffrey Chaucer reached his eternal destination before his storytelling pilgrims reached their earthly destination in The Canterbury Tales. Often writers simply lose interest in a project. Probably every archive holding printed matter contains unpublished manuscripts.

For various reasons books occasionally do not make it into a reader’s hands; and so the book that might-have-been acquires a sort of mystique. “A lost book,” writes Stuart Kelly in The Book of Lost Books: An Incomplete History of All the Great Books You’ll Never Read (2005), “is susceptible to a degree of wish fulfillment. The lost book, like the person you never dared asked to the dance, becomes infinitely more alluring simply because it can be perfect only in the imagination.” The simplest form of loss, notes Kelly, is destruction. An infamous example is the legendary Library of Alexandria, supposedly holding all the wisdom of the ancient world, burning to ashes in a single night. Other books are sacrificed to carelessness, as when a certain publisher moved offices, absentmindedly leaving behind manuscripts in a building slated for immediate demolition. Some books never achieve completion because of the death of the author, as when Charles Dickens expired before solving The Mystery of Edwin Drood, or Geoffrey Chaucer reached his eternal destination before his storytelling pilgrims reached their earthly destination in The Canterbury Tales. Often writers simply lose interest in a project. Probably every archive holding printed matter contains unpublished manuscripts.

The Wheaton College Archives & Special Collections houses a few such documents, material undoubtedly meant to be edited, packaged and distributed to the public, but is now foldered neatly in acid-free boxes and shelved in a climate-controlled facility. A brief survey follows:

The second president of Wheaton College, Dr. Charles Blanchard, left for posterity Psychological Foundations, a book-length manuscript discovered as a worn, yellowed roll in the Blanchard home in 1949 by Dr. Clyde Kilby and Miss Julia Blanchard. It advances Blanchard’s observations regarding the development of the “soul life.”

The late Dr. Joe McClatchey (SC-45), professor of English at Wheaton College, wrote The Praise of God in Literature: From Homer to Hopkins, a 400-page study of worship in western literature as seen throughout the centuries.

Jeanne Murray Walker (SC-72), poet, playwright and Professor of English at the University of Delaware, penned a young adult novel entitled Stranger, dated 1989. Though her editors were favorable and encouraged revision, the book was not published.

Academic Arthur Christy (SC-82), recipient of the Guggenheim Fellowship for Intellectual History and American Literature, committed several years to researching The Thoreau Fact Book, reflecting his interest in the New England transcendentalists. It remained unfinished upon his death in 1946.

The brilliant missionary and political professor, Dr. Kenneth Landon (SC-38), husband of Margaret Landon, author of Anna and the King of Siam, composed an unpublished history of Malaya, along with several uncollected short stories, some of which initially appeared in the Saturday Evening Post.

And, among the papers of Madeleine L’Engle (SC-03), author of A Wrinkle in Time, lay several unpublished manuscripts, including sermons, short stories, retreat addresses, a handwritten novel called The Feast of Stephen and a nearly completed novel called A Lost Innocent, featuring Camilla, who first appeared in Camilla Dickinson (1951) and later in A Live Coal in the Sea (1996). Also archived is the text for an illustrated children’s book titled Moses, Prince of Egypt, intended for release with the 1998 DreamWorks animated film.

Though “lost” to the general public, these works are fortunately still available for inspection in Wheaton’s Manuscript Reading Room.

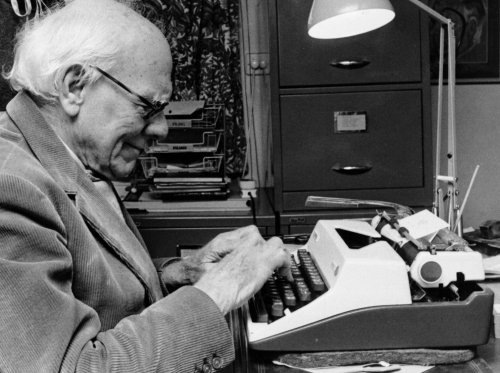

Malcolm Muggeridge Papers…25 year anniversary

As 2010 finished out it marked the 25th anniversary of the acquisition of Malcolm Muggeridge’s Papers and the 15th anniversary of their dedication . Canon David Winter gave the dedicatory address entitled “Seeing Through The Eye: Muggeridge, the Prophet of the Media Age.” A commemorative booklet including the entire dedication program on November 18, 1995 was made available. The noteworthy event was also featured in a full-page article in the Wheaton’s student newspaper, The Record .

As 2010 finished out it marked the 25th anniversary of the acquisition of Malcolm Muggeridge’s Papers and the 15th anniversary of their dedication . Canon David Winter gave the dedicatory address entitled “Seeing Through The Eye: Muggeridge, the Prophet of the Media Age.” A commemorative booklet including the entire dedication program on November 18, 1995 was made available. The noteworthy event was also featured in a full-page article in the Wheaton’s student newspaper, The Record .

Malcolm Muggeridge, born in 1903, has become one of the notable figures of the twentieth century. He is well-known as an author, journalist, media personality, and in his later years, a leading spokesman for Christianity. Malcolm Muggeridge experienced a life of tension and seeking. Beginning with his socialist upbringing, his father was involved in politics and served as a member of Parliament, his search for satisfaction and justice continued until it culminated in his finally embracing Christianity.

Malcolm was first and foremost a writer and thinker, who contributed greatly to the literature and thought of the twentieth century. As Canon David Winter stated,

The true value of having Malcolm’s papers at Wheaton College comes through being able to preserve “the voice of a craftsman of the English language–and a Christian voice which speaks with all the more splendor because it was born from a seed that was full of doubt, cynicism and self-promotion.

The Papers of Malcolm Muggeridge are available to researchers at the Wheaton College Archives & Special Collections.

“Where the Law of God is the Law of the Land…”

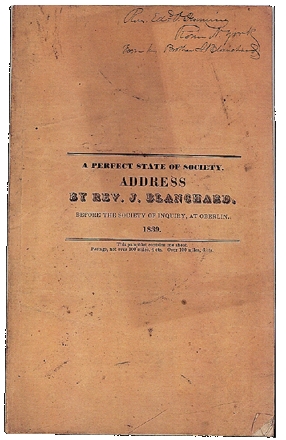

January 19 is the birthday of Jonathan Blanchard and 2011 marks the bicentennial of his birth. Blanchard had several careers of significance prior to his coming to the dreary open prairies of Wheaton Illinois in the late 1850s. He had taken great risks as one of “The Seventy” disciples of abolitionism. He was a very successful pastor in Cincinnati. He was active in getting the Liberty Party in Ohio off the ground and was friend of future members of Congress and the U. S. Supreme Court, even serving to introduce the two. He was offered a professorship of the fledgling Oberlin College and the presidency of a vibrant activist mission institute. In addition he represented his nation at the second World’s Anti-Slavery Convention in London and served as one of its vice-presidents. He also publicly debated the sinfulness of slavery with a fellow minister over four days for hours each day (these were later published and can easily be found in bookshops and libraries worldwide). He also debated Stephen Douglass. Finally, before his trek from the prosperous Galesburg to Wheaton, Jonathan Blanchard served as the second president of Knox College. His able skills brought the school recognition and solid finances.

January 19 is the birthday of Jonathan Blanchard and 2011 marks the bicentennial of his birth. Blanchard had several careers of significance prior to his coming to the dreary open prairies of Wheaton Illinois in the late 1850s. He had taken great risks as one of “The Seventy” disciples of abolitionism. He was a very successful pastor in Cincinnati. He was active in getting the Liberty Party in Ohio off the ground and was friend of future members of Congress and the U. S. Supreme Court, even serving to introduce the two. He was offered a professorship of the fledgling Oberlin College and the presidency of a vibrant activist mission institute. In addition he represented his nation at the second World’s Anti-Slavery Convention in London and served as one of its vice-presidents. He also publicly debated the sinfulness of slavery with a fellow minister over four days for hours each day (these were later published and can easily be found in bookshops and libraries worldwide). He also debated Stephen Douglass. Finally, before his trek from the prosperous Galesburg to Wheaton, Jonathan Blanchard served as the second president of Knox College. His able skills brought the school recognition and solid finances.

In this midst of this great career was an address that Jonathan Blanchard gave to the Society of Inquiry at Oberlin College in 1839. It was this address, A Perfect State of Society, that Jonathan Blanchard detailed his hopes and aspirations for a nation. It was these ideals that shaped his life and career as he sought to ameliorate the ills of society to usher in a state of society that would be ready for the reign of Jesus Christ. It was not that the world and society would have reached sinlessness but that things were in such order, where what needed restraint was restrained, that there was harmony. Like children need discipline, so too elements of society needed structure and restraint.

In this midst of this great career was an address that Jonathan Blanchard gave to the Society of Inquiry at Oberlin College in 1839. It was this address, A Perfect State of Society, that Jonathan Blanchard detailed his hopes and aspirations for a nation. It was these ideals that shaped his life and career as he sought to ameliorate the ills of society to usher in a state of society that would be ready for the reign of Jesus Christ. It was not that the world and society would have reached sinlessness but that things were in such order, where what needed restraint was restrained, that there was harmony. Like children need discipline, so too elements of society needed structure and restraint.

In The Perfect State of Society Blanchard sought to:

- Specify some things which we are not to expect; — and

- Some things we ARE to look for in a Perfect State of Society.

- Suggest some of the ways and means by which this desired condition of things is to come.

Blanchard didn’t want his listeners, and later his readers, to misunderstand. This perfect state of society was not a return to Edenic glory. It was a place where the Gospel had done for all what it could do for one. The Gospel’s function was to restore and reclaim. This society would “take up sinful mortals and fit them for heaven.” “Society is perfect where what is right in theory exists in fact; where practice coincides with principle and the law of God is the law of the land.”

If one wants to understand the life and mind of Jonathan Blanchard, particularly on this bicentennial, then one must understand and engage A Perfect State of Society. This address will not only help you understand this forgotten figure of 19th-century American history, but it will help you understand the time in which he lived–a time filled with Utopian ideals.

– Download A Perfect State of Society, 1839 (17 pages)

Epiphany and Judgment

Over twenty years ago, Special Collections author Frederick Buechner penned the following words in the 1989 Advent — Epiphany issue of the Anglican Digest.

We are all of us judged every day. We are judged by the face that looks back at us from the bathroom mirror. We are judged by the faces of the people we love and by the faces and lives of our children and by our dreams. Each day finds us at the junction of many roads, and we are judged as much by the roads we have not taken as by the roads we have.

The New Testament proclaims that at some unforeseeable time in the future God will ring down the final curtain on history, and there will come a day on which all our days and all the judgments upon us and all our judgments upon each other will themselves be judged. The judge will be Christ. In other words, the one who judges us most finally will be the one who loves us most fully.

Romantic love is blind to everything except what is lovable and lovely) but Christ’s love sees us with terrible clarity and sees us whole. Christ’s love so wishes our joy that it is ruthless against everything in us that diminishes our joy. The worst sentence love can pass is that we behold the suffering which love has endured for our sake, and that is also our acquittal. The justice and mercy of the judge are ultimately one.

The Papers of Frederick Buechner are available to researchers at the Wheaton College Archives & Special Collections.

We never have worked pleasantly together….

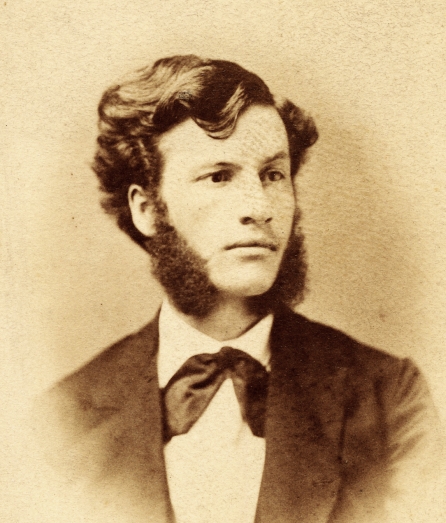

In late June 1871, the twenty-two year old Charles Blanchard wrote to his mother about his travels from Worcester, Massachusetts to Bailey Hollow, Pennsylvania. Following his graduation from Wheaton College in 1870 Charles lectured on behalf of the National Christian Association, a reform organization dedicated chiefly to opposing Freemasonry and other oath bound orders. By the time he graduated from Wheaton College in 1870, he had presented 65 addresses concerning the ills of lodgery.

In late June 1871, the twenty-two year old Charles Blanchard wrote to his mother about his travels from Worcester, Massachusetts to Bailey Hollow, Pennsylvania. Following his graduation from Wheaton College in 1870 Charles lectured on behalf of the National Christian Association, a reform organization dedicated chiefly to opposing Freemasonry and other oath bound orders. By the time he graduated from Wheaton College in 1870, he had presented 65 addresses concerning the ills of lodgery.

Among other topics, Charles references Asa Packer and the founding and operation of Lehigh University. He also writes of his uncertainty for his future as he considered law, ministry or taking a stab at newspapers. It is obvious that this had been a topic of conversation of Charles with his parents.

Knowing that his father, Jonathan, had bouts of illness and poor health Charles feared that if his father’s health were to fail terribly that the college would become a “timeserving nerveless thing.” Likely reflecting hiss own concern Jonathan urged Charles to begin working at Wheaton. Despite his father’s desires and his own aimlessness, Charles tells his mother that his father and he have “never have worked pleasantly together and can do nothing in such a work unless we did.” Charles obviously had struggled with his father and wrote of Jonathan, he “will stand for his convictions as no other man I know.” Charles eventually came to terms with his father and his headstrong personality. In 1872, Charles began the affiliation with Wheaton College which was to last the rest of his life. That year he took the position of Principal of the Preparatory Department.

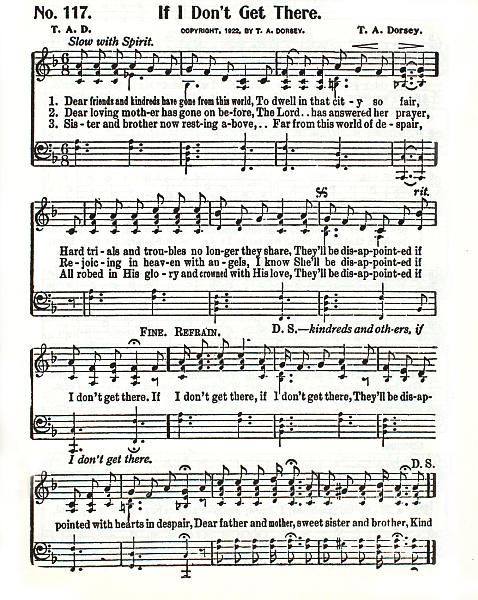

Gospel Pearls

Two hundred and ten years ago African Methodist Episcopal Church founder Richard Allen published A Collection of Spiritual Songs and Hymns, selected from various authors. The first hymnal published with the intent to serve the black church, Allen sought to divert black worshipers away from the official Methodist hymnal. Within the first year a second edition was published. The hymnal, pocket-sized at 3″ x 5″, was known to be popular, however few copies are known to exist and only microfilm editions are listed in OCLC’s Worldcat. One reason this seminal hymnal is so important is that it reflected the songs that black Christians in America enjoyed singing and that were popular. Allen’s hymnal is the precursor of the gospel hymnal of nearly a century later.

One hundred and twenty years after Allen’s hymnal made it into the hands of worshipers Gospel Pearls was published. Despite the large numbers of gospel hymnals in the marketplace and in churches, the publishers of Gospel Pearls, the National Baptist Convention Sunday School Publishing Board, made no apology for its availability citing the “present day needs of the Sunday school, Church, Conventions and other religious gatherings” since its songs were “suitable for Worship and Devotion, Evangelistic Services, Funeral, Patriotic and other special occasions.”

One hundred and twenty years after Allen’s hymnal made it into the hands of worshipers Gospel Pearls was published. Despite the large numbers of gospel hymnals in the marketplace and in churches, the publishers of Gospel Pearls, the National Baptist Convention Sunday School Publishing Board, made no apology for its availability citing the “present day needs of the Sunday school, Church, Conventions and other religious gatherings” since its songs were “suitable for Worship and Devotion, Evangelistic Services, Funeral, Patriotic and other special occasions.”

This hymnal, found in the Special Collection’s Hymnal Collection (SC 15-1208), was created under the direction of Willa Townsend and contained 164 songs, including works by white gospellers like Sankey, Bradbury, Bliss, Crosby and Rodeheaver, but also works by black writers like Charles Tindley, Lucie Campbell, and, notably, Thomas A. Dorsey. Townsend included one of her own works in Gospel Pearls, “Wade in the Water.”

Tindley is recognized as one of the founding fathers of American gospel music, but it was Dorsey who would have the biggest impact on this musical form.  Songs written in Dorsey’s musical style were called “dorseys” and were a combination of Christian praise and rhythm and blues and jazz music stylings. Incorporating much of late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century hymnody’s emphasis upon personal experience, Dorsey’s gospel songs influenced mainstream white music, both secular and sacred. Gospel Pearls included Dorsey’s “If I Don’t Get There,” but he was famous for his song “Precious Lord, Take My Hand.” So beloved was this song that it was recorded by a wide range of singers, both black and white, like Albertina Walker, Elvis Presley, Mahalia Jackson, Aretha Franklin, Jim Reeves, Roy Rogers, and Tennessee Ernie Ford and many many more. It was also the requested song for the funerals of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Lyndon B. Johnson.

Songs written in Dorsey’s musical style were called “dorseys” and were a combination of Christian praise and rhythm and blues and jazz music stylings. Incorporating much of late-nineteenth and early-twentieth century hymnody’s emphasis upon personal experience, Dorsey’s gospel songs influenced mainstream white music, both secular and sacred. Gospel Pearls included Dorsey’s “If I Don’t Get There,” but he was famous for his song “Precious Lord, Take My Hand.” So beloved was this song that it was recorded by a wide range of singers, both black and white, like Albertina Walker, Elvis Presley, Mahalia Jackson, Aretha Franklin, Jim Reeves, Roy Rogers, and Tennessee Ernie Ford and many many more. It was also the requested song for the funerals of Martin Luther King, Jr. and Lyndon B. Johnson.

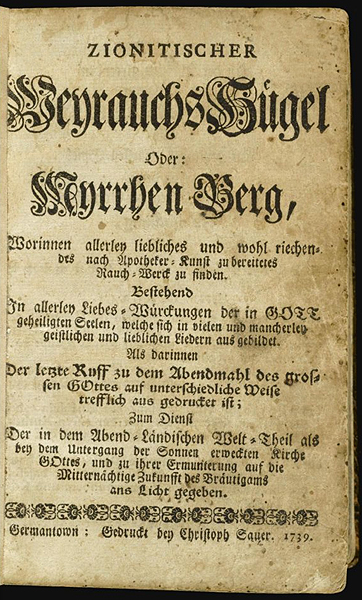

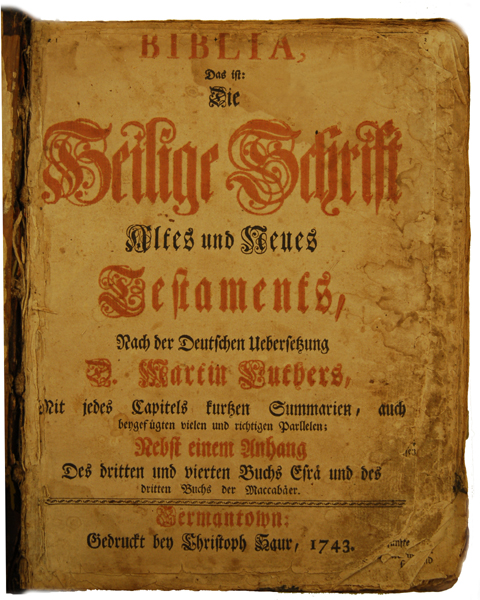

“For the glory of God and my neighbor’s good”

One would think that Wheaton College would have one of the best bible collections around–at least among small colleges. Unfortunately, this is not the case. However, over time and through purchasing and gifts it is possible for Wheaton expand its current holdings. One way in which the Archives & Special Collections has expanded its holding is through the acquisition of several collections that had been a part of the holdings of the Billy Graham Center Museum and Library. One such gem that came via the museum was a copy the first bible printed in America in an European language (German). A later edition of this bible became known as the “gun-wad bible” because during the Battle of Germantown (1777) during the American Revolution British soldiers broke into the printer’s shop and confiscated thousands of pages of the yet completed bibles and used them for gun-wadding.

Christopher Sauer, born Johann Christoph Sauer in 1695, sailed to America with his wife and young son in 1724 and nearly fifteen years later had established a thriving printing business. Historians have recognized Christopher Sauer (also known to history as Johann Christoph Sauer, Christoph Saur, Christoph Sauer and Christopher Sower) as one of the most important figures of colonial Pennsylvania. Sauer was known as a separatist and did not seem to be a part of any particular religious community, though his wife had moved to the Ephrata commune near Germantown, leaving the senior and junior Christoph.

In 1743 Saur printed the first European-language Bible printed in America. The only bible printed in America prior to this was John Eliot’s Algonquin Bible (1663). Sauer’s bible was a huge undertaking and became a 1267 page volume. This is considered one of the largest printing ventures in America at the time. Eventually the 1200 copies printed were sold. Though he was a business man he made it known that those who were poor and could not afford his bible could ask to receive one. Sauer’s son eventually printed a second edition in 1763 and a third in 1776 (mentioned above) — all before Robert Aitken’s “Congress Bible” of 1782.

As would reflect the future nature of American religion, Sauer’s bible created controversy and division even before it was finished. Area Lutheran and Reformed clergy feared the translation chosen, Berleberg’s, along with some of the printing’s typographical errors would confusion readers and encourage heresy. Sauer did not help his situation by using multiple translations in a single book (Job). Despite the pressure Sauer pressed on.

To date about two hundred of Sauer’s publications have been identified. His press, which he built himself, was quite active and produced a steady stream of devotional and theological works. Some of the earliest hymnals for German speakers came from Sauer’s press. In fact the first publication off of his press was a hymnal that was reprinted over and over again. The type was sent to him from Germany by Christopher Shutz. Sauer was well-acquainted with revivalist George Whitefield and had hopes of printing devotional and theological works in English, including a quarto-sized bible, but the high cost of paper proved a hurdle too great.

To date about two hundred of Sauer’s publications have been identified. His press, which he built himself, was quite active and produced a steady stream of devotional and theological works. Some of the earliest hymnals for German speakers came from Sauer’s press. In fact the first publication off of his press was a hymnal that was reprinted over and over again. The type was sent to him from Germany by Christopher Shutz. Sauer was well-acquainted with revivalist George Whitefield and had hopes of printing devotional and theological works in English, including a quarto-sized bible, but the high cost of paper proved a hurdle too great.

His motto for his press was “For the glory of God and my neighbor’s good.” Sauer wrote to a patron in September, 1740, that “I would rather serve my neighbor and glorify God in that way than to gather a large earthly fortune for myself or for my son….” He continued, saying, “that nothing shall be printed except that which is to the glory of God and for the physical or eternal good of my neighbors. What ever does not meet this standard, I will not print. I have already rejected several, and would rather have the press standing idle. I am happier when I can distribute something of value among the people for a small price, than if I had a large profit without a good conscience.” He was known for his charitable works, so much so that he was known as “Bread Father” and the “Good Samaritan” of Germantown. It is said that he would meet German immigrants as they arrived on ships provide hospitality to the sick and needy.

Sauer did what he could to expand his work and to make his publications affordable. He had heard of a printer in Philadelphia that claimed knowing the formula for a better ink and Sauer inquired about learning the formula. Asking what the printer would ask in return for teaching Sauer the printer asked Sauer to build him a press like his own. Saying he would consider the trade Sauer later thought to myself, “You have carried on twenty-six trades and crafts without any teacher, and made almost all of the tools necessary for them. Why should you now pay so dearly for this knowledge?” The next morning he had an idea on how to make the a new ink. The ink was as good and even cheaper than the old.

Sauer did what he could to expand his work and to make his publications affordable. He had heard of a printer in Philadelphia that claimed knowing the formula for a better ink and Sauer inquired about learning the formula. Asking what the printer would ask in return for teaching Sauer the printer asked Sauer to build him a press like his own. Saying he would consider the trade Sauer later thought to myself, “You have carried on twenty-six trades and crafts without any teacher, and made almost all of the tools necessary for them. Why should you now pay so dearly for this knowledge?” The next morning he had an idea on how to make the a new ink. The ink was as good and even cheaper than the old.

Christopher Sauer died on September 25, 1758, after a remarkable career in America. During his thirty-four years in America his press operation and intellectual interests put him at the forefront of many of the important controversial political and theological issues of his day. About one fifth of the publications of his press were translations or reprints of European books, largely theological or devotional in nature. These productions helped to maintain America’s European ties. Conversely, many of Sauer’s American works were reprinted in Europe, bringing ideas from the New World to the Old.

This entry in indebted to Donald Durnbaugh’s wonderful article on Sauer.

[Durnbaugh, Donald F. “Christopher Sauer Pennsylvania-German Printer: His Youth in Germany and Later Relationships with Europe.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 82, No. 3 (Jul., 1958), pp. 316-340.]

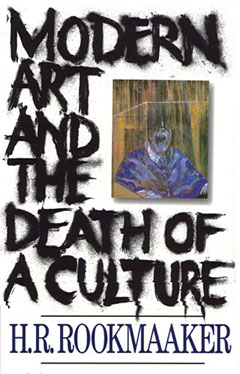

Rookmaaker & Modern Art…40 years later

This year marks the 40th anniversary of Hans Rookmaaker’s classic, Modern Art and the Death of a Culture. In his groundbreaking work, Rookmaaker offers pointed perspectives on the counter-cultural turmoil of the 1960s as reflected in its art. He examines histories, themes and reactions in classic and contemporary creative endeavor; and urgently calls Christian artists to bold commitment in executing their unique roles as prophets and messengers. He was impatient with naive questions or lazy, unfocused thinking. Church audiences who blithely dismissed modern art received a not-so-gentle chide: “How can you say that modern art is ugly when you worship the Lord in a building painted like this?” In talks and writing, Hans Rookmaaker sought to address the disastrous severance of truth and beauty from divine revelation. He argued that there is no true beauty divorced from truth, love and freedom, either in art or life. “We are Christians whether we sleep, eat or work hard,” he writes in Art Needs No Justification (1978), “whatever we do, we do it as God’s children.”

This year marks the 40th anniversary of Hans Rookmaaker’s classic, Modern Art and the Death of a Culture. In his groundbreaking work, Rookmaaker offers pointed perspectives on the counter-cultural turmoil of the 1960s as reflected in its art. He examines histories, themes and reactions in classic and contemporary creative endeavor; and urgently calls Christian artists to bold commitment in executing their unique roles as prophets and messengers. He was impatient with naive questions or lazy, unfocused thinking. Church audiences who blithely dismissed modern art received a not-so-gentle chide: “How can you say that modern art is ugly when you worship the Lord in a building painted like this?” In talks and writing, Hans Rookmaaker sought to address the disastrous severance of truth and beauty from divine revelation. He argued that there is no true beauty divorced from truth, love and freedom, either in art or life. “We are Christians whether we sleep, eat or work hard,” he writes in Art Needs No Justification (1978), “whatever we do, we do it as God’s children.”

Henderik “Hans” Roelof Rookmaaker, art historian, professor, author and lecturer, was born in 1922 in the Netherlands and spent his early years living in Sumatra (Indonesia). After returning to Holland in 1933, Hans developed a lifelong passion for jazz music. Following the German Occupation in 1940, Hans was interned for distributing anti-Nazi leaflets. After World War II, Rookmaaker moved to Amsterdam and studied art history, integrating philosophy with Christian doctrine. He authored many books pertaining to art theory, art history and music. Lecturing throughout the 1960s and ’70s on university campuses and conferences in the U.S. and U.K., he endeared himself to a generation of questioning students. The Papers of Hans Rookmaaker are available to researchers in the college’s Archives & Special Collections.

Henderik “Hans” Roelof Rookmaaker, art historian, professor, author and lecturer, was born in 1922 in the Netherlands and spent his early years living in Sumatra (Indonesia). After returning to Holland in 1933, Hans developed a lifelong passion for jazz music. Following the German Occupation in 1940, Hans was interned for distributing anti-Nazi leaflets. After World War II, Rookmaaker moved to Amsterdam and studied art history, integrating philosophy with Christian doctrine. He authored many books pertaining to art theory, art history and music. Lecturing throughout the 1960s and ’70s on university campuses and conferences in the U.S. and U.K., he endeared himself to a generation of questioning students. The Papers of Hans Rookmaaker are available to researchers in the college’s Archives & Special Collections.