Oak Park, Illinois, located eight miles west of the Chicago Loop, is the home of notable contributors to national and world culture. For example, here lived novelist Ernest Hemingway, as did Edgar Rice Burroughs, creator of Tarzan and John Carter of Mars. Architect Frank Lloyd Wright designed several of his famous structures at his Oak Park studio; and James Dewar, inventor of the late, lamented Twinkie, resided amid the solace of its tree-lined avenues. Oak Park is also the childhood home of Dr. Wallace Broecker, who coined the now-ubiquitous phrase “global warming” in a 1975 essay titled “Climate Change: Are we on the brink of a pronounced global warming?”

As a child, Broecker attended Harrison Street church in Oak Park with his parents. The small assembly was led by T. Leonard Lewis, who would later serve as pastor of First Baptist Church of Hammond, Indiana, before serving as president of Gordon-Conwell Seminary in Masschussetts until his death in 1959.

Broecker, encouraged to attend Wheaton College because his neighborhood friend, “Ernie” Sandeen, enrolled, recalls campus mischief in Fixing Climate: What Past Climate Changes Reveal About the Current Threat – And How to Counter It (2008), written with Robert Kunzig:

Broecker, encouraged to attend Wheaton College because his neighborhood friend, “Ernie” Sandeen, enrolled, recalls campus mischief in Fixing Climate: What Past Climate Changes Reveal About the Current Threat – And How to Counter It (2008), written with Robert Kunzig:

It has a reputation as the Harvard of evangelical colleges, an ambitious but also a godly place, where students signed a pledge to adhere to the same set of rules that applied to Harrison Street…It was a serious place…and it seemed to force into full flower the most profoundly unserious aspect of Broecker’s character, one that can still be startling today to the uninitiated…At Wheaton the pranks got more elaborate. In his junior year he was business manager of the yearbook, which position of influence allowed him to sign excuses that got him and his friends out of daily chapel. It also got him a key to the attic of Blanchard Hall, where college memorabilia was stored. That October, Broecker discovered an unused door leading from the attic into the bell tower, which was off-limits to students; the custodian kept the main entrance carefully padlocked. At midnight on Halloween night Broecker, Sandeen and their roommates woke the campus with a loud tolling. When the custodian came racing into the bell tower, they exited through the attic and locked him in. He was forced to ring the bells again to summon the police. By the time the law arrived the Broecker gang had retreated to a ground-floor classroom. Broecker remembers vividly the flashlight beams coming through the windows and playing along the walls as he and his friends hugged the floor, out of sight.

Broecker offers an interesting perspective on the 1951 revival…and his subsequent drift from Evangelical Christianity:

In addition to going to chapel every day, Wheaton students were required to spend a week every year rededicating themselves to Christ under the guidance of a visiting preacher. That year the event took an extraordinary turn – it became a mass public confession. For three days and nights students lined up in the choir loft and behind the pulpit, waiting for their chance to proclaim their sins. The pressure to participate was intense. Broecker sat there in turmoil, brooding more seriously than he had ever brooded over anything. He certainly had sins – violations of the Wheaton pledge, for instance, that went beyond dancing. (He has never liked dancing.) But he knew some of of the people who were confessing, and he knew they weren’t being honest. They were holding back on the juicy stuff. The hypocrisy of the whole spectacle revolted him – people were pretending to believe in rules they couldn’t really live by, and then pretending to confess their violations of those rules. Hypocrisy and dishonesty, Broecker realized, were the sins he could least abide. That day in chapel, he slipped the fragile line that had tied him to the Rock.

Moving into the field of scientific research, Broecker found a substitute:

[Science] is the belief that if we observe the world carefully, test our ideas skeptically, and communicate honestly, we can figure things out. That summer of 1952, Broecker was converted to science. In time he would come to think of it as something sacred.

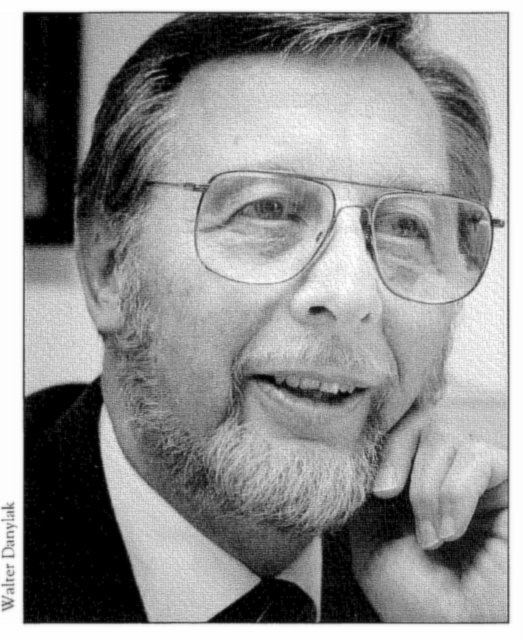

Wallace S. Broecker attended Wheaton College for three years before transferring to Columbia where he graduated. He is the Newberry Professor of Earth and Environmental Sciences at Columbia University. In 2006 he received the Crafoord Prize in Geosciences.