Adam Smith asked, “What can be added to the happiness of a man who is healthy, who is out of debt, and who has a clear conscience?”

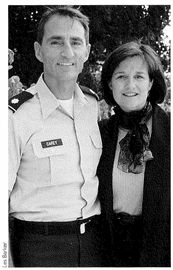

I can think of at least another thing: the privilege of coming alongside someone and encouraging him on his journey through life. This will be my last opportunity to do that at Wheaton College in my current capacity, as I begin my fourth and final year serving as the College’s professor of military science for Army Reserve Officers’ Training Corps–or ROTC. However, my wife, Beth, and I look forward to another year of meeting more Wheaton College students, engaged couples, and ROTC cadets experiencing God in their own unique ways.

The opportunity to mentor someone is one of the greatest privileges we have. Although I am often discouraged by my own sinfulness and feelings of inadequacy, I am energized by those who have a hunger to grow in the ways of the Lord and are eager for someone to encourage them along the way.

I relish the opportunity to explain to a young man or woman who is considering serving his or her country that the military is desperately in need of godly leaders. Students often do not consider the military as a mission field, so I tell them the Army is in need of leaders who can share the gospel of grace with their fellow officers and soldiers all over the world.

Beth and I have made some lasting memories with students who have befriended us. We try to encourage them as they prepare for an uncertain future. And although we may think we know the right answer for some dilemma, instead of telling them directly, we try to guide them through the process, letting them figure it out.

As Beth and I have opened our home to students, we have found that regardless of what we feed them, they are quite content just to be in a family environment. I say it is Beth’s gourmet cooking they enjoy, but she says it’s because they just want a home–cooked meal.

We have been blessed through our facilitating the engaged couples’ seminar alongside Dean of Students Rich Powers and his wife, Jennifer. It is so gratifying to see young people work out their plans to make a lifelong commitment to a future mate. Another opportunity for mentoring has come during the gatherings of Women Who Make a Difference, a group that meets twice a semester and allows women of all generations to come together with women students for fellowship.

This Puritan prayer has helped to guide me for many years, and I pray it will be the heart–cry of my students:

Thou hast given Thyself for me,

may I give myseif to Thee;

Thou has died for me,

may I live to Thee,

in every moment of my time,

in every movement of my mind,

in every pulse of my heart.

May I never daily with the world and its allurements,

but walk by Thy side,

listen to Thy voice,

be clothed with Thy graces,

and adorned with Thy righteousness.

—–

Twenty years ago, the Wheaton Alumni magazine began a series of articles, titled “On My Mind”, in which Wheaton faculty told about their thinking, their research, or their favorite books and people. Former Professor of Military Science, Randy Carey (who taught at Wheaton since 1996-1999) was featured in the Autumn 1999 issue.

The following statement was included at the time of publication:

Lieutenant Colonel Randy Carey has been Wheaton’s professor of military science since 1996. He holds a bachelor’s degree from Washington State University in business administration, an M.B.A. from the Florida Institute of Technology, and an M.A. in theology from Wheaton. He was commissioned in the artillery in March 1978 and was assigned to Germany. His last assignment before coming to Wheaton was in the Pentagon, working for the Chief of Staff of the Army. LTC Carey also was an assistant professor of military science at Rochester Institute of Technology in New York. He and his wife, Beth, have three sons: Ryan (12), Tyler (10), and Max (4).

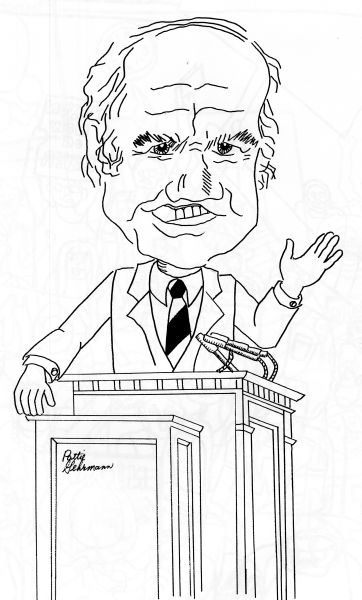

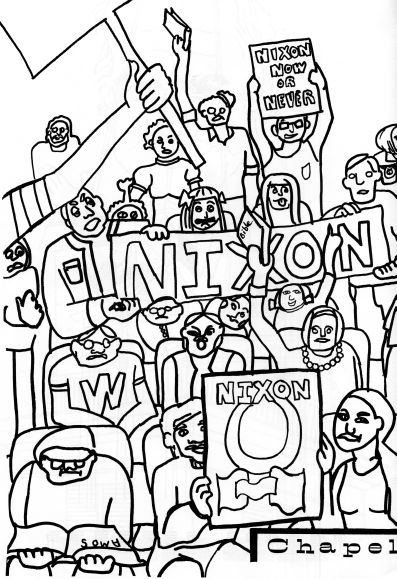

The event was initially suggested by McGovern’s staff, asking for a venue in which he might engage Evangelicals. Activist Jim Wallis, attending Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, was asked to organize the senator’s visit, arranging a breakfast with prominent Christian leaders, in addition to an engagement at Wheaton College. “Actually,” writes Wallis, “the Wheaton Student Council, which issued the invitations to both candidates, accidentally switched the letters, sending Nixon’s by mistake to McGovern.” However, only McGovern accepted. A quiet man raised in a devout Methodist family, McGovern soon found himself in the pulpit of Edman Chapel, standing before an atypically divided house. A few supportive students cheered his unpopular anti-Vietnam War position, but many more booed, waving pro-Nixon banners.

The event was initially suggested by McGovern’s staff, asking for a venue in which he might engage Evangelicals. Activist Jim Wallis, attending Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, was asked to organize the senator’s visit, arranging a breakfast with prominent Christian leaders, in addition to an engagement at Wheaton College. “Actually,” writes Wallis, “the Wheaton Student Council, which issued the invitations to both candidates, accidentally switched the letters, sending Nixon’s by mistake to McGovern.” However, only McGovern accepted. A quiet man raised in a devout Methodist family, McGovern soon found himself in the pulpit of Edman Chapel, standing before an atypically divided house. A few supportive students cheered his unpopular anti-Vietnam War position, but many more booed, waving pro-Nixon banners.

Wallis also remembers:

Wallis also remembers: