One of the venerable institutions of the Windy City is the Union League Club, whose stately, 23-story clubhouse is located on Jackson Blvd. This brief description from their website encapsulates its history and mission:

One of the venerable institutions of the Windy City is the Union League Club, whose stately, 23-story clubhouse is located on Jackson Blvd. This brief description from their website encapsulates its history and mission:

Established in 1879 to uphold the sacred obligations of citizenship, promote honesty and efficiency in government, and support cultural institutions and the beautification of the city, the Club has been a contributing partner in the growth and development of Chicago. Through the efforts of its dynamic membership, the Club has been a catalyst for action in nonpartisan political, economic and social arenas – focusing its leadership and resources on important social issues.

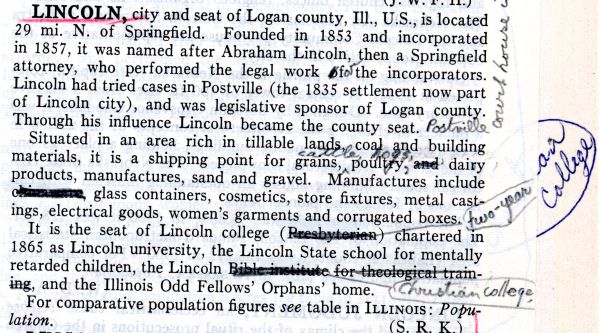

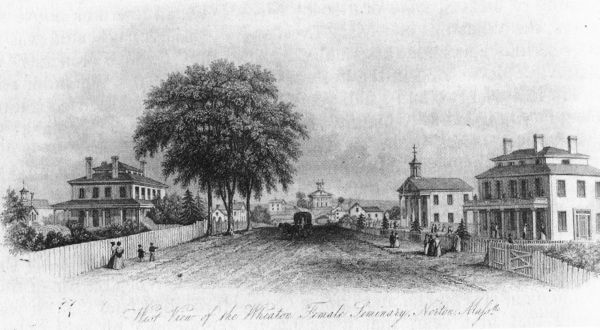

Laying the groundwork for various philanthropic projects, the prestigious Club was instrumental in persuading the United States Congress to choose Chicago as the location for the 1893 Colombian Exposition. Honorary members included Theodore Roosevelt, Calvin Coolidge, Herbert Hoover, Douglas MacArthur and Dwight Eisenhower. Its influential resident membership played vital roles in establishing cultural landmarks such as Orchestra Hall, the Field Museum and the Harold Washington Library. Aside from its civic pursuits, the Club has significantly interacted with Wheaton College and contributed, though indirectly, to the establishment of one other evangelical institution.

Wallace Heckman, serving as the twenty-fourth president of the Union League Club in 1904, was the law partner of Cyrus Blanchard, brother of Charles Blanchard, second president of Wheaton College and son of its founder, Jonathan Blanchard. Heckman’s summer retreat on the Rock River in Oregon, Illinois, provided a hospitable attraction for the Eagle’s Nest Art Colony, consisting of Chicago writers, painters, actors and sculptors seeking refuge from the blistering city heat.

Victor F. Lawson, founder, editor and publisher of the Chicago Daily News, donated Lawson Field, where Wheaton College baseball players and other student athletes still practice. Lawson was a member and heavy financial contributor to the Club. Harold “Red” Grange and other proment football players from the 1920s were invited by the Club to a luncheon in 1953 as the “All-American Eleven.” Grange grew up in Wheaton and his papers (SC-20) are archived in the Special Collections at Wheaton College.

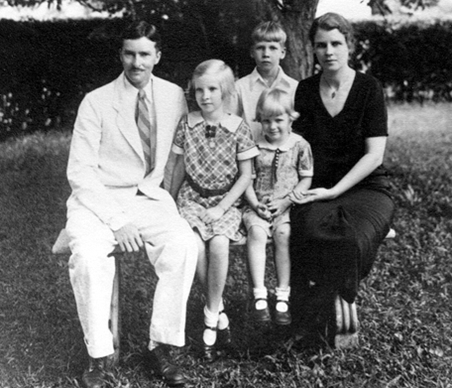

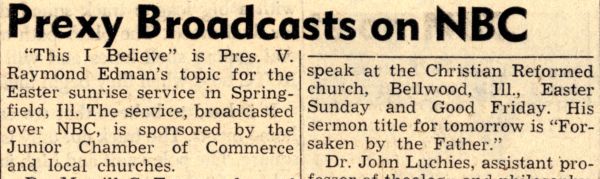

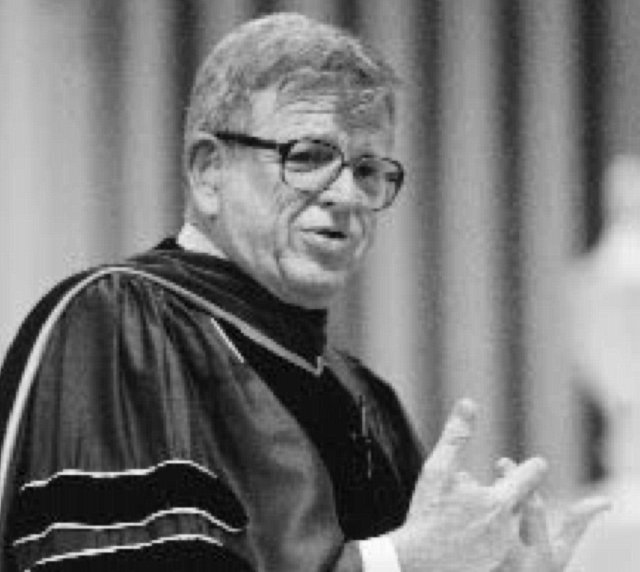

Brothers Herman and Raymond Fischer, longtime trustees and graduates of Wheaton College, were members of the Union League Club, as was alumn and publisher Robert Van Kampen. War hero W. Wyeth Willard, chaplain and assistant to president Dr. V. Raymond Edman, was a member. Edman’s brother, Elner, was also a member. Charles Blanchard Weaver, vice-president of the Northern Trust Company, college trustee and great-grandson of Jonathan Blanchard, served as president of the Union League Club from 1962-3. In 1983, Dr. Richard Chase, the sixth president of Wheaton College, was asked by Jerry Rose, president of Chanel 38, to deliver a lecture to the Club, speaking on any topic. Chase chose, “The Marks of an Influential Man.”

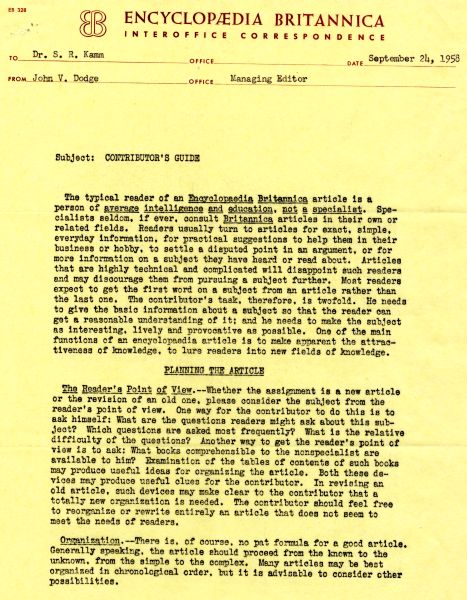

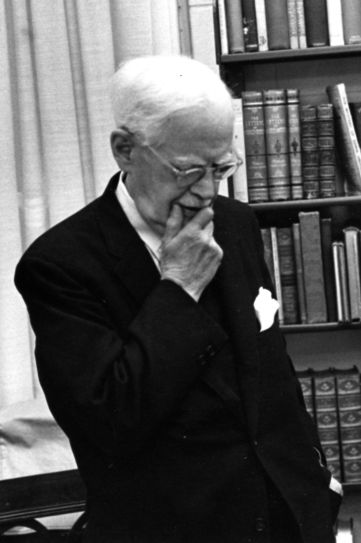

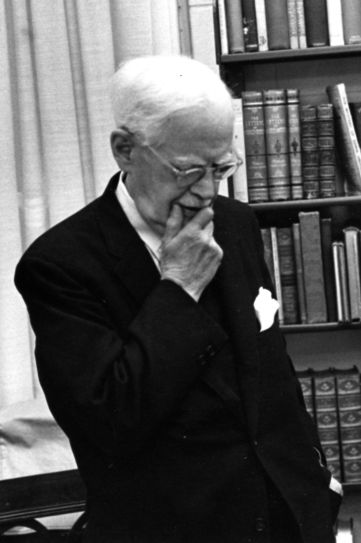

William Akin of Evanston, chairman of the library committee and librarian for the Union League Club, wrote book reviews for the Club’s magazine, Union League Men and Events.  He dedicates one page in the March, 1950, issue to Wheaton College authors, discussing The Soil Runs Red by Matthew S. Evans, Uninterrupted Sky by Paul Hutchens and Never Dies the Dream by Margaret Landon. “Wheaton scores again,” writes Akin, “literally and spiritually…” Reviewing in the October, 1950, issue, Akin praises W. Wyeth Willard’s Fire on the Prairie, writing, “…When I reread certain passages I blush with shame for the plush manner in which I secured what education I did and I am certain some professors and instructors in many of our present-day colleges, if they would only read this history of Wheaton College, would regard their efforts a sham.” Akin is supremely complimentary about Willard: “He is closer to seven feet tall than six feet…Personally, I would hate to tangle with him but having met him I hate to be away from him.” William Akin, avid collector of rare books, donated his personal collection (SC-01) to Wheaton College as a memorial to Dr. Edman after the beloved president died in 1967.

He dedicates one page in the March, 1950, issue to Wheaton College authors, discussing The Soil Runs Red by Matthew S. Evans, Uninterrupted Sky by Paul Hutchens and Never Dies the Dream by Margaret Landon. “Wheaton scores again,” writes Akin, “literally and spiritually…” Reviewing in the October, 1950, issue, Akin praises W. Wyeth Willard’s Fire on the Prairie, writing, “…When I reread certain passages I blush with shame for the plush manner in which I secured what education I did and I am certain some professors and instructors in many of our present-day colleges, if they would only read this history of Wheaton College, would regard their efforts a sham.” Akin is supremely complimentary about Willard: “He is closer to seven feet tall than six feet…Personally, I would hate to tangle with him but having met him I hate to be away from him.” William Akin, avid collector of rare books, donated his personal collection (SC-01) to Wheaton College as a memorial to Dr. Edman after the beloved president died in 1967.

The Club intersects with the development of another Christian school – not west of Chicago like Wheaton, but located on the West Coast. During the mid-1940s, radio evangelist Charles E. Fuller, host of The Old Fashioned Revival Hour, purchased land near Pasadena, California, realizing his dream of establishing a Christian college. Searching for capable faculty, Fuller invited Wilbur Smith, professor of English Bible at Moody Bible Institute, who donated thousands of volumes, providing the nucleus for Fuller’s library; and Harold Ockenga, president of the National Association of Evangelicals (SC-113), to serve as head the school. According to Fuller’s biography, Give the Winds a Mighty Voice, Ockenga, returning to Boston from an NAE meeting in Omaha, convened with Fuller and Smith in Chicago:

The historic meeting was held in a private room at the Union League Club of Chicago. Wilbur Smith wanted to know what position Harold Ockenga would occupy in the seminary. He would be president in absentia for the time being, Harold Ockenga replied. He would work to recruit the charter faculty and map out the curriculum. Then they agreed that if three faculty members, besides Wilbur Smith, would be willing to start teaching by that next September, they would then go ahead with this earlier date. They also agreed to meet again a month hence in Chicago in the offices of Herbert J. Taylor’s Christian Workers’ Foundation in the Civic Opera Building.

Thus began Fuller Theological Seminary, organized in the private, luxurious confines of the Club.

And so the Union League Club, rigorously elitist, joins hands with Wheaton and Fuller, proponents of the faith described as “the most exclusive club in the world of which anyone can be a member.”

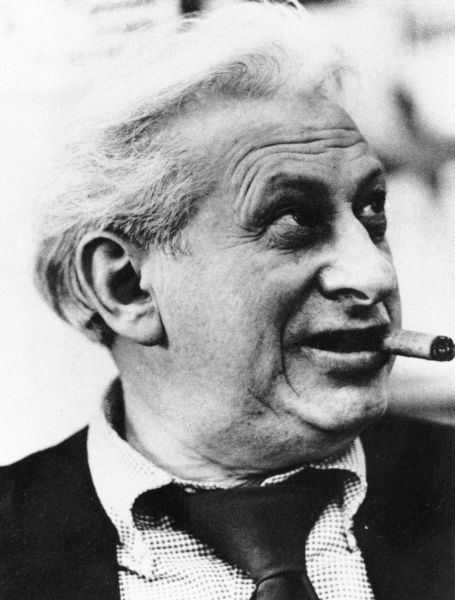

A graduate of the University of Chicago and the Chicago Law School, he acted on stage and radio and wrote scripts for WGN, among many other jobs. Forever curious, he hosted his own radio show on WFMT, enthusiastically interviewing scores of fascinating writers, actors and politicians, signing off with his signature, “Take it easy, but take it.” He acquired his nickname from James T. Farrell’s trilogy, Studs Lonigan, about a Southside Irish family struggling during the Depression.

A graduate of the University of Chicago and the Chicago Law School, he acted on stage and radio and wrote scripts for WGN, among many other jobs. Forever curious, he hosted his own radio show on WFMT, enthusiastically interviewing scores of fascinating writers, actors and politicians, signing off with his signature, “Take it easy, but take it.” He acquired his nickname from James T. Farrell’s trilogy, Studs Lonigan, about a Southside Irish family struggling during the Depression.With a great deal of respect and affection, Studs Terkel.