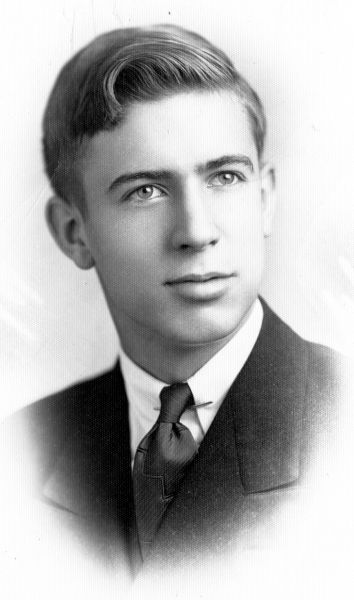

Arthur Schulert, born on a farm near Gladwin, MI, was third among eight children. He accepted Christ at age nine. A lad possessing determination, he conquered his stuttering in high school while participating in the debate club. From there he enrolled at Wheaton College, studying chemistry, squeezing four years into three. He then enrolled at Ohio State for one quarter before transferring to Princeton, pursuing his graduate degree while assisting with the Manhattan Project. Briefly pausing his scientific studies, he took theological training at Grace Seminary in Winona Lake, IN, while teaching part-time at Taylor University. Schulert earned his Ph.D in biochemistry at the University of Michigan in 1951. Downplaying his abilities, he insisted that “It doesn’t take brains – just perseverance.” In addition to acquiring a degree at Michigan, he also found a wife – Ruth Darling – while attending InterVarsity Christian Fellowship meetings. After marrying the couple moved to New York City. In 1955 he joined Lamont Geochemical Laboratory, researching the effects of often-lethal radioactive fallout, specifically “Strontium 90,” a man-made variant of the metal that seeks human bone, causing in large doses bone cancer and leukemia. During the late ’50s Schulert frequently appeared on television, discussing the danger of nuclear radiation and environmental abuse. His pioneering research was covered by Newsweek, Time, Life and the New York Times.

Arthur Schulert, born on a farm near Gladwin, MI, was third among eight children. He accepted Christ at age nine. A lad possessing determination, he conquered his stuttering in high school while participating in the debate club. From there he enrolled at Wheaton College, studying chemistry, squeezing four years into three. He then enrolled at Ohio State for one quarter before transferring to Princeton, pursuing his graduate degree while assisting with the Manhattan Project. Briefly pausing his scientific studies, he took theological training at Grace Seminary in Winona Lake, IN, while teaching part-time at Taylor University. Schulert earned his Ph.D in biochemistry at the University of Michigan in 1951. Downplaying his abilities, he insisted that “It doesn’t take brains – just perseverance.” In addition to acquiring a degree at Michigan, he also found a wife – Ruth Darling – while attending InterVarsity Christian Fellowship meetings. After marrying the couple moved to New York City. In 1955 he joined Lamont Geochemical Laboratory, researching the effects of often-lethal radioactive fallout, specifically “Strontium 90,” a man-made variant of the metal that seeks human bone, causing in large doses bone cancer and leukemia. During the late ’50s Schulert frequently appeared on television, discussing the danger of nuclear radiation and environmental abuse. His pioneering research was covered by Newsweek, Time, Life and the New York Times.

Though Schulert labored in laboratories among the variables of powerful natural and artificial forces, he offered comfort with this thought: “The One who made the world also gave us His Word, the Bible. In the Bible we find that Jesus Christ offers His power and very life to those who will trust Him.  This power transforms man’s self-destroying nature and imparts eternal life to the believer’s soul. The Christian, in the face of nuclear perils, can confidently repeat after the Apostle Paul, ‘All things work together for good to them that love God.'” He never felt that modern scientific advances discredited the Bible. If there seemed to be a contradiction, the difference may result from either misinterpretation of the scriptures or ascribing undue finality to scientific pronouncements. As evidence accumulates, he felt, science would more closely confirm the Bible.

This power transforms man’s self-destroying nature and imparts eternal life to the believer’s soul. The Christian, in the face of nuclear perils, can confidently repeat after the Apostle Paul, ‘All things work together for good to them that love God.'” He never felt that modern scientific advances discredited the Bible. If there seemed to be a contradiction, the difference may result from either misinterpretation of the scriptures or ascribing undue finality to scientific pronouncements. As evidence accumulates, he felt, science would more closely confirm the Bible.

In 1966 he joined the Vanderbilt University Medical School Biochemistry faculty, and four years later founded the Environmental Science Corporation where he served as president and CEO. Schulert and Ruth were active members of the Village Baptist Church, Gideons International and the Tennessee Organization of Professional Speakers. He delivered in 1968 an address entitled “Wheaton’s Survival Amidst Rapid Change and Rising Federalism” to the annual Wheaton College Scholastic Honor Society. Dr. Arthur Schulert died in 1993, survived by his wife, five sons and two daughters. Appropriately, his funeral, pre-arranged by Schulert himself, was “…a time of praise and thanksgiving.” Its theme: “It is well with my soul.” Schulert’s papers (SC-175), comprising correspondence and published articles, are housed at Wheaton College Special Collections.

On October 30, 1997

On October 30, 1997

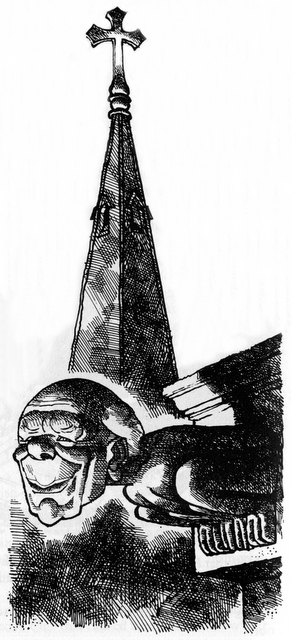

The adoption of Muggeridge as a modern gargoyle was not in stone, the work of a skilled stonemason, but in caricature, the work of the famous cartoonist, Wally Fawkes, better known as Trog. It is extraordinary that the depiction of Malcolm Muggeridge as a gargoyle in ink reached a vastly larger audience than would ever be achieved by one of stone. The depiction was very apt and appropriate given Muggeridge’s fascination with gargoyles and his desire to identify himself with them so frequently in his writing and broadcasts.

The adoption of Muggeridge as a modern gargoyle was not in stone, the work of a skilled stonemason, but in caricature, the work of the famous cartoonist, Wally Fawkes, better known as Trog. It is extraordinary that the depiction of Malcolm Muggeridge as a gargoyle in ink reached a vastly larger audience than would ever be achieved by one of stone. The depiction was very apt and appropriate given Muggeridge’s fascination with gargoyles and his desire to identify himself with them so frequently in his writing and broadcasts.