Twenty years ago, the Wheaton Alumni magazine began a series of articles in which Wheaton faculty told about their thinking, their research, or their favorite books and people. Professor of Mathematics Terry Perciante was featured in the February/March 1992 issue.

The Washington Monument stands outside my hotel room window. To the right, I can see the Lincoln Memorial and the White House, shining in the setting Sunday evening sun. This morning I attended the church where Abraham Lincoln worshiped during his presidency and where Scottish immigrant Peter Marshall ministered to multitudes of World War II servicemen.

The Washington Monument stands outside my hotel room window. To the right, I can see the Lincoln Memorial and the White House, shining in the setting Sunday evening sun. This morning I attended the church where Abraham Lincoln worshiped during his presidency and where Scottish immigrant Peter Marshall ministered to multitudes of World War II servicemen.

But sightseeing is not the reason for my visit to Washington. I am part of a three-person team representing the Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory. With representatives from seven other Department of Energy national labs, we will seek to formulate and implement strategies for increasing the effectiveness of mathematics and science education in our nation’s schools. The National Academy of Science, the Mathematical Sciences Education Board, the Department of Energy, the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, and other agencies are uniting to provide funds for an extensive and long-term effort to stimulate American mathematics and science education.

The tranquility of the monuments and government buildings outside my window is not shared by the schools in our nation. Tomorrow morning they will fill with young people and then deliver education that is measurably inferior to that which is provided by schools in most other industrialized countries.

What can we do to help our students, individuals who will populate this capital city as leaders and citizens in the years ahead? They will certainly need a profound understanding of many scientific and deeply technical issues. Old ways of knowing will not adequately serve citizens during our age of subatomic particle physics, space exploration and astrophysics, fractal geometry and dynamical systems, biological engineering, and the chemistry of superconducting materials.

Unfortunately, most college faculty (even those who view themselves as liberally educated) remain so mathematically and scientifically illiterate that they cannot comprehend books and articles from those disciplines, which so profoundly shape modern life and decision making. What educational hope can there be for our young people?

Indictment of the causes for malaise in American education and culture is altogether too easy. The loss of a national consensus relative to the nature of education, the effects of urban congestion, the decline of social structures such as the family, and other factors could offer excuses for a lack of personal response to the problems.

If believers abdicate their influence in society to people who are not grounded in the love of God and the light of his revelation, then who will act? Lincoln’s action in the midst of a national social crisis and Marshall’s ministry to those in spiritual crisis both provide examples of the kind of commitment that our current educational problems require.

In our meetings, the Fermilab team will seek to join strategies and resources in order to achieve the maximum effect on our young people’s mathematical and scientific growth. And right now, as I return to the laptop computer on my desk, I’ll write another page in a series of books aimed at improving the teaching of mathematics at the secondary and college level.

In April, and again in July, I’ll join with my German and American coauthors to present seminars in Nashville and Chicago that detail wonderful advances in mathematics, but explain them at a level appropriate for secondary school mathematics teachers. By God’s grace, I want others to see me as an individual who loves his discipline and who wants others to become quantitatively enabled so that they can render more effective service than I can.

Would that we could all become people who are not conformed to standards of educational mediocrity, but are instead transformed and made capable of communicating with people who need to know his mercy and grace. The task involves serving Christ well while also serving young people within an educational system that needs reform.

Together, the multitude of Christian mathematics and science educators in our nation can provide living monuments to Christ’s transforming power in the face of overwhelming odds. If God has given special analytical abilities, considerable mathematical and scientific preparation, and opportunities to teach others, then surely by offering these special abilities to the Lordship of the Christ of creation, opportunities will be given by him to apply these gifts in ministries to people and to the educational infrastructure of our nation.

May God enable all of us to become humble agents of change and conveyors of new life in our disciplines, professions, and communities.

———-

Terry Perciante received the bachelor of science degree from Wheaton in 1967 and the Ed.D. from the State University of New York at Buffalo in 1972, when he began teaching at Wheaton. He was named Wheaton’s Junior Teacher of the Year in 1977 and Senior Teacher of the Year in 1994. In 1990, he was one of 700 educators from private colleges across the nation who was recognized by The Sears-Roebuck Foundation for resourcefulness and leadership. He is a member of the National Council of Teachers of Mathematics, and is an organizing force behind Project Teacher, a program funded by the Lilly Endowment. Since 1988 Terry has increasingly worked in fractal geometry and chaos theory with a small international team of writers and researchers headquartered at the University of Bremen in northern Germany. His professional involvement with this team has resulted in his presenting frequent keynote talks at NSF institutes, symposia, and professional meetings especially relating to aspects of dynamical systems.

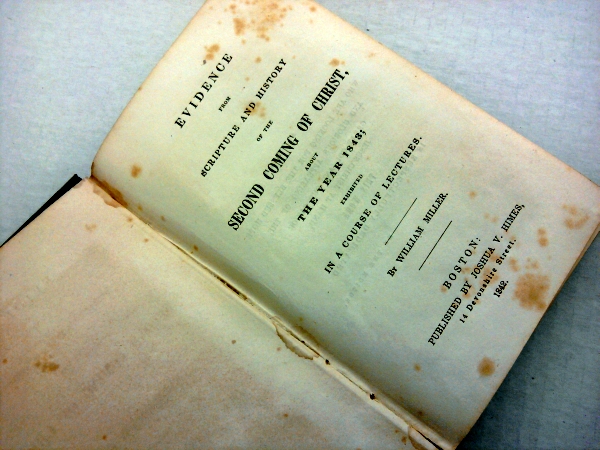

It is said that tomorrow, May 21, 2011 is Judgment Day. Billboards around America have declared that the end is near and that Christ will return. Over the course of the subsequent five months the earth will be destroyed. In the history of American religion this is not a new tale or theology. It has been here before, even for the contemporary prognosticator (who once before predicted the end to happen in September 1994).

It is said that tomorrow, May 21, 2011 is Judgment Day. Billboards around America have declared that the end is near and that Christ will return. Over the course of the subsequent five months the earth will be destroyed. In the history of American religion this is not a new tale or theology. It has been here before, even for the contemporary prognosticator (who once before predicted the end to happen in September 1994).