The following article was taken from the December 1981/January 1982 issue of the Wheaton Alumni Magazine. It celebrated the life and ministry of Evan Draper Welsh, Wheaton College chaplain, who passed away 37 years ago today.

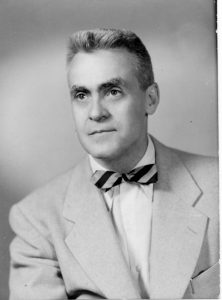

Evan Draper Welsh ’27, D.D. ’55, who served for 26 years as chaplain to Wheaton College students and alumni, died early on December 17, 1981. He suffered congestive heart failure in his home in Wheaton, and died shortly after entering Central DuPage Hospital.

Born on September 3, 1904, in Princeton, Illinois, Evan spent his boyhood in Newton, Kansas, Long Beach, California, and Elgin, Illinois, before enrolling in Wheaton Academy. While attending Wheaton College, he served as president of his freshman class and as captain of the football team his senior year. Additionally, Evan’s activities at Wheaton included membership in the Excelsior Literary Society, the Y.M.C.A. Cabinet, and participation in varsity debate.

Following graduation, he did graduate work at Princeton Theological Seminary and the University of Minnesota, where he studied English literature. While at Minnesota, Evan pastored Bethany Presbyterian Church on the college campus.

In 1933, he accepted a call to pastor the College Church in Wheaton, where his father had served. During his 13 years there, he became very active on the Wheaton College campus. He also continued graduate study at Northwestern University, completing the M.A. in philosophy in 1938. Evan moved to Detroit in 1946 to pastor the 1700-member Ward Presbyterian Church. He also taught at Detroit Bible College.

In 1955 Evan received an invitation from President V. Raymond Edman to accept the newly-created position of college chaplain on Wheaton’s campus. The new chaplain, who also served as assistant professor of Bible, was awarded the doctor of divinity degree from the College that same year.

During his 15 years as chaplain, Evan became endeared to countless students through his helpful counsel, his faithful visits to the health center and local hospitals, and the traditional ‘open house’ hosted each weekend at his home.

Evan retired from his post as chaplain in 1970, but continued in the capacity of alumni chaplain until his death. Even when on vacation he poured himself into building and renewing friendships with alumni, and encouraging them in their Christian faith.

Evan’s outreach extended to the community through the teaching and visitation ministries of the College Church of Wheaton until his death. His popularity as a summer Bible conference speaker occupied much time in his earlier years. Evan’s commitment to spread the Gospel worldwide fired is involvement in the evangelism service and national and foreign missions of the United Presbyterian Church, U.S.A.

At the time of his death Evan was survived by his wife, Olena Mae Hendrickson ’41, of Wheaton, two daughters and eight grandchildren. He was preceded in death by his first wife, Evangeline Mortenson ’27.

The relationships we value most become our greatest losses. In the homegoing of Dr. Evan Draper Welsh ’27, Wheaton College suffers the loss of an institution and countless thousands find a vacancy in their lives where a deep friendship had been.

But the ministry of that life continues. From his perspective, Evan Welsh’s gift to us was only a means to an end. His love for us rose from a desire that we might know the love of a greater Friend, and commit ourselves to that One.

Evan Welsh would not want praise lavished upon his life. The tributes given to him underline the purposes of his life. He related those goals in an article in The Tabernacle Bulletin, 1961.

I am increasingly convinced that the true source of happiness for the growing child of God is the setting of certain high and definite goals for his or her life, and then, the giving oneself to the achieving of those goals. Surely this is what Paul had in mind when he wrote in Colossians 3:1-4: ‘If ye then be risen with Christ, seek those things which are above, where Christ sitteth on the right hand of God. Set your affection on things above, not on things on the earth. For ye are dead, and your life is hid with Christ in God. When Christ, who is our life shall appear, then shall ye also appear with Him in glory.’

“The other day with the glory of God in mind, and thinking of the peace of heart that comes when God is truly glorified, I sat down and listed several high goals that I believed the Lord wanted me to strive for. I listed seven, and I really believe they are relevant for every Christian’s life. They’ve already blessed my own soul, and if sharing them gives new direction and fire to some other Christian I shall be thankful.”

Evan proceeded to list the following goals: disciplined growth in godliness; growth in the knowledge of the Word of God; prayer; soul winning; witnessing throughout the world; cultivating a strong church life; and undertaking the “rich ‘adventures in friendship’ which await that one who will prove himself friendly.”

“These goals are high,” Evan continued. “They’re difficult. They’re costly. But I believe they are Biblical, and that the ones who to make them the core of their lives will have a new zest for living — and the life here will more and more resemble that in Glory.”

We pay tribute to a man who ran untiringly toward his goals. We thank a loving family who shared themselves and their dear one so freely. And we thank the Lord for His servant, Evan Draper Welsh, who reminded us of the beautiful reality of life in Christ.

“For the path of the just is as a shining light, that shineth more and more unto the perfect day.” (Proverbs 4:18)

See also: Highway to Heaven – Sesquicentennial snapshot

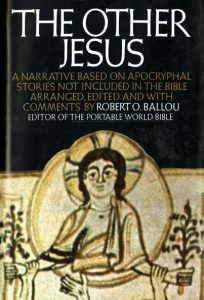

Associated primarily with the Viking Press, his deeply ecumenical interests are reflected in the titles of the books he edited: The Portable World Bible (including selections from sacred volumes), The Nature of Religion, The Bible of the World and The Other Jesus: A Narrative Based on Apocryphal Stories Not Included in the Bible. In 1938 he wrote This I Believe: A Letter to My Son, relating his personal faith.

Associated primarily with the Viking Press, his deeply ecumenical interests are reflected in the titles of the books he edited: The Portable World Bible (including selections from sacred volumes), The Nature of Religion, The Bible of the World and The Other Jesus: A Narrative Based on Apocryphal Stories Not Included in the Bible. In 1938 he wrote This I Believe: A Letter to My Son, relating his personal faith. Laity Lodge, situated in the Frio River Valley near Leakey, Texas, overlooks a magnificent vista of forested hills and jagged rock. Far from urban chaos, this retreat stands as a haven for those needing to explore pressing questions, absorb the peace of the Spirit, or simply run into God.

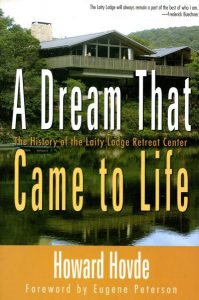

Laity Lodge, situated in the Frio River Valley near Leakey, Texas, overlooks a magnificent vista of forested hills and jagged rock. Far from urban chaos, this retreat stands as a haven for those needing to explore pressing questions, absorb the peace of the Spirit, or simply run into God.

This statement summarizes Muriel’s relentless love of learning. Afflicted with a “spastic” leg ailment in addition to her blindness, Muriel managed to convey a radiant love for people and education. “There is nothing that she will not try or do,” wrote a former grade school teacher, “and she wants no sympathy.”

This statement summarizes Muriel’s relentless love of learning. Afflicted with a “spastic” leg ailment in addition to her blindness, Muriel managed to convey a radiant love for people and education. “There is nothing that she will not try or do,” wrote a former grade school teacher, “and she wants no sympathy.”

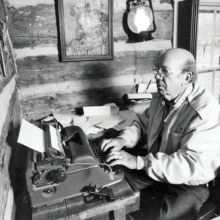

Presenting himself as a backwoods “bootleg” hayseed, wearing cowboy boots and straw hats, he actually possessed a fine intellect, abundant courage and quick wit. Campbell, siding unhesitatingly with the oppressed and disenfranchised, was one of four who boldly escorted African American students, known as the “Little Rock Nine,” into the racially segregated Little Rock Central High School in 1957. Campbell was also the only white man to attend the founding of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1957.

Presenting himself as a backwoods “bootleg” hayseed, wearing cowboy boots and straw hats, he actually possessed a fine intellect, abundant courage and quick wit. Campbell, siding unhesitatingly with the oppressed and disenfranchised, was one of four who boldly escorted African American students, known as the “Little Rock Nine,” into the racially segregated Little Rock Central High School in 1957. Campbell was also the only white man to attend the founding of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1957.

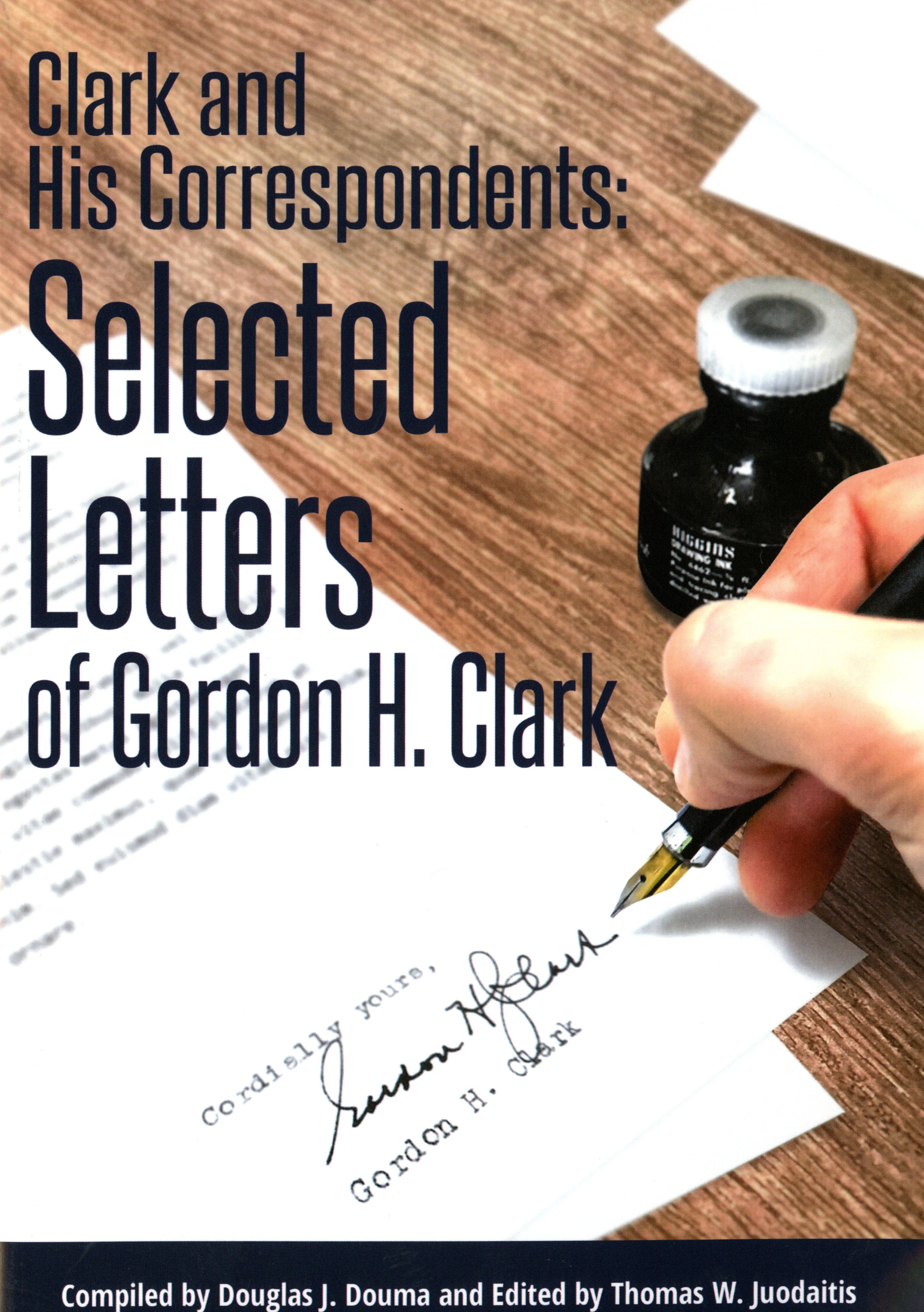

Compiled by Douglas J. Douma and edited by Thomas W. Juodatis, Clark and His Correspondents: Selected Letters of Gordon H. Clark (2017) presents an array of Clark’s exchanges with such prominent evangelical and fundamentalist leaders as J. Oliver Buswell, V. Raymond Edman, E.J. Carnell, Cornelius Van Til, Carl F.H. Henry and J. Gresham Machen. The compilation uses many letters scanned from the College Archives of Buswell Library.

Compiled by Douglas J. Douma and edited by Thomas W. Juodatis, Clark and His Correspondents: Selected Letters of Gordon H. Clark (2017) presents an array of Clark’s exchanges with such prominent evangelical and fundamentalist leaders as J. Oliver Buswell, V. Raymond Edman, E.J. Carnell, Cornelius Van Til, Carl F.H. Henry and J. Gresham Machen. The compilation uses many letters scanned from the College Archives of Buswell Library.