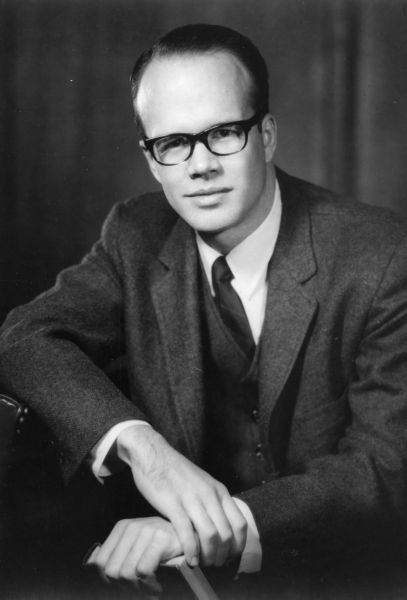

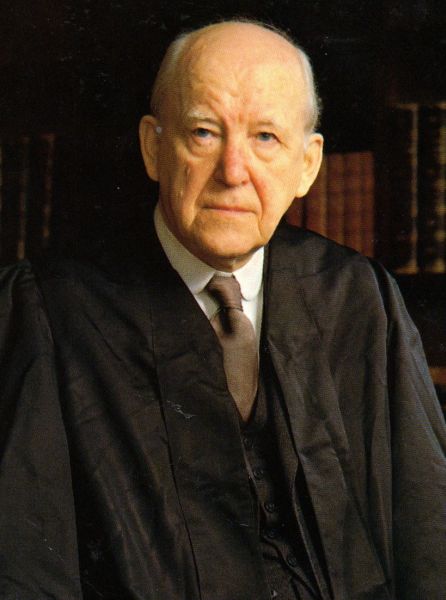

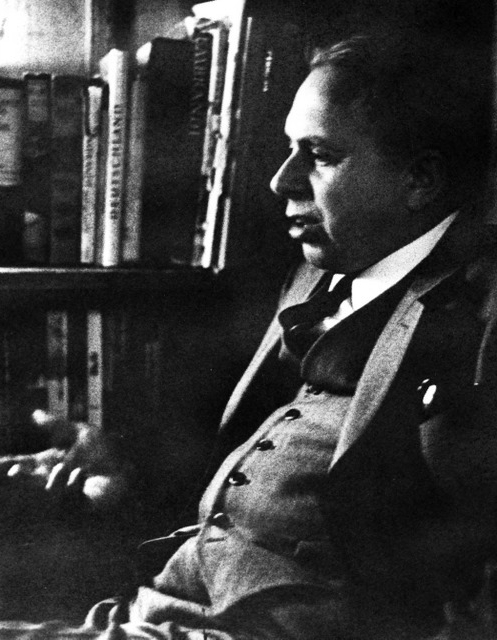

Dr. Philip Ryken, Wheaton College’s newly inaugurated eighth president, previously served as pastor of Tenth Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia. Before assuming that role, Ryken served as assistant to its senior pastor, Dr. James Montgomery Boice. Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Boice received his early education at Stony Brook school on Long Island, continuing at Harvard where he was awarded his A.B. degree with high honors in English Literature. Two years later in 1962 he earned his master’s degree in theology from Princeton before pursuing doctoral studies at the University of Basel, Switzerland, supervised by instructors such as Karl Barth. In 1969 Time magazine recognized Boice’s efforts in “revitalizing the urban scene” in downtown Philadelphia where the almost-200 year old church is located. Dr. Boice preached the 1974 Wheaton College Special Services during the first week of April. For the morning chapel services, titled “Thoughts for Troubled Times,” he drew from the book of Habbakuk. For the evening sessions, held in Pierce Chapel, Boice shared “Conversations with Christ,” derived from the Gospel of John. In addition to hosting the National Bible Study Hour radio broadcast, Boice authored several books, including Foundations of the Christian Faith, Psalms, Gospel of Matthew and What Ever Happened to the Gospel of Grace? Boice died as the result of liver cancer at age 61 in 2000.

Dr. Philip Ryken, Wheaton College’s newly inaugurated eighth president, previously served as pastor of Tenth Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia. Before assuming that role, Ryken served as assistant to its senior pastor, Dr. James Montgomery Boice. Born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Boice received his early education at Stony Brook school on Long Island, continuing at Harvard where he was awarded his A.B. degree with high honors in English Literature. Two years later in 1962 he earned his master’s degree in theology from Princeton before pursuing doctoral studies at the University of Basel, Switzerland, supervised by instructors such as Karl Barth. In 1969 Time magazine recognized Boice’s efforts in “revitalizing the urban scene” in downtown Philadelphia where the almost-200 year old church is located. Dr. Boice preached the 1974 Wheaton College Special Services during the first week of April. For the morning chapel services, titled “Thoughts for Troubled Times,” he drew from the book of Habbakuk. For the evening sessions, held in Pierce Chapel, Boice shared “Conversations with Christ,” derived from the Gospel of John. In addition to hosting the National Bible Study Hour radio broadcast, Boice authored several books, including Foundations of the Christian Faith, Psalms, Gospel of Matthew and What Ever Happened to the Gospel of Grace? Boice died as the result of liver cancer at age 61 in 2000.

Tragedy and Faith – Scott & Janet Willis

Sixteen years ago on November 8, 1994, Scott and Janet Willis were traveling outside Milwaukee, Wisconsin with the six youngest of their nine children. Scott was a pastor at the Parkwood Baptist Church in the Mt. Greenwood neighborhood on Chicago’s Far Southwest Side and Janet schooled the six younger children at their home on the second story of the church. In an instant their lives were forever changed as a piece of metal debris on the road punctured their gas tank and their minivan erupted in flames. The couple barely escaped with their lives as the inferno blazed throughout the van, instantly killing five of the children still buckled in their seats (Joe, Sam, Hank, Elizabeth, and Peter, ages 11 years to 6 weeks). Thirteen year old, Ben escaped the burning van but later died at the hospital with third degree burns over 90% of his body.

Sixteen years ago on November 8, 1994, Scott and Janet Willis were traveling outside Milwaukee, Wisconsin with the six youngest of their nine children. Scott was a pastor at the Parkwood Baptist Church in the Mt. Greenwood neighborhood on Chicago’s Far Southwest Side and Janet schooled the six younger children at their home on the second story of the church. In an instant their lives were forever changed as a piece of metal debris on the road punctured their gas tank and their minivan erupted in flames. The couple barely escaped with their lives as the inferno blazed throughout the van, instantly killing five of the children still buckled in their seats (Joe, Sam, Hank, Elizabeth, and Peter, ages 11 years to 6 weeks). Thirteen year old, Ben escaped the burning van but later died at the hospital with third degree burns over 90% of his body.

This horrific tragedy would throw this Chicago pastor and his family into the international spotlight and eventually lead to the imprisonment of former Illinois Governor George Ryan. The deaths of the Willis children came to symbolize the infamous licenses-for-bribes political scandal during Ryan’s tenure as Secretary of State before his election as Governor in 1999.

A year after the accident, the Willis’ bravely spoke before the Wheaton College chapel on November 17, 1995, to share their personal story of tragedy and testimony of faith. In subsequent years, they moved to Tennessee in 2004 and have been blessed with 25 grandchildren from their surviving three older children.

.

A Wray of Hope

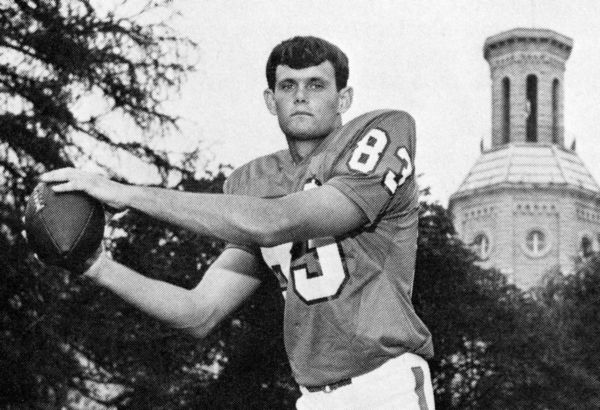

When Wayne Wray initially enrolled at Wheaton College, his desire as a student was to pursue veterinary medicine and oceanography, reflecting his passion for the outdoors. He wrote on his application: “I can offer Wheaton a life dedicated to Christ and believe your acceptance of me will give me advantages I will not find in all colleges. My hope is in Christ and I commit all things to His leadership.” As a sophomore in the fall of 1972, his goal as an athlete was to be the defensive starting end for the Crusaders. Through grueling practice and determination he earned the position. During his first starting game as a varsity football player, playing against Millikan University, he received a critical injury, a fractured and dislocated fourth cervical. Suddenly he was paralyzed from the neck down. He endured three major surgeries in three days. Each time the neurosurgeons declared, “No hope.”  As he lay motionless in the intensive care unit, drifting in and out of consciousness, Wayne prayed and sought God’s will for his life, now so dramatically altered. Strengthened by his faith and the constant encouragement of friends and family, Wayne did not surrender to despondency. Instead, he set objectives and accomplished them one by one, tackling his rehabilitation with the same focus with which he’d played ball. He learned to type, write and print. “He cheers and lifts you up when you go to see him,” visitors remarked. “He’s not bitter, he would play again if his body were healed.” Wayne decided that he would encourage others as a profession.

As he lay motionless in the intensive care unit, drifting in and out of consciousness, Wayne prayed and sought God’s will for his life, now so dramatically altered. Strengthened by his faith and the constant encouragement of friends and family, Wayne did not surrender to despondency. Instead, he set objectives and accomplished them one by one, tackling his rehabilitation with the same focus with which he’d played ball. He learned to type, write and print. “He cheers and lifts you up when you go to see him,” visitors remarked. “He’s not bitter, he would play again if his body were healed.” Wayne decided that he would encourage others as a profession.

To assist with medical expenses, classmates raised $100,000 for the “Wray of Hope” campaign. In 1972 Wayne returned to Wheaton College to receive an honorary degree. Following that he earned his associate’s degree from Springfield Technical Community College and his bachelor’s degree from Northern Colorado University. Fulfilling his desire to help others who’d experienced similar injuries, he received his master’s degree in rehabilitation counseling in 1982. That year he also married Jeanette Gaffney, a physical therapist. The wedding was performed by his Wheaton roommate, Scott McClellen. Though Wayne provided a shining beacon for victims of spinal injuries, he faced one more challenge in 1986 when he was diagnosed with cancer. After battling illness for several months, he died at age 34 on January 4, 1987, at his home in Ocala, Florida. As he’d indicated on his college application, he did truly “commit all things to His leadership.” Wayne’s football coach at Wheaton College, Gary Taylor, observed at the funeral, “He taught us about courage because he faced unbelievable odds and time and again beat them…He set goals, saying, ‘If I can only get by today, then I can start on tomorrow.'”

To assist with medical expenses, classmates raised $100,000 for the “Wray of Hope” campaign. In 1972 Wayne returned to Wheaton College to receive an honorary degree. Following that he earned his associate’s degree from Springfield Technical Community College and his bachelor’s degree from Northern Colorado University. Fulfilling his desire to help others who’d experienced similar injuries, he received his master’s degree in rehabilitation counseling in 1982. That year he also married Jeanette Gaffney, a physical therapist. The wedding was performed by his Wheaton roommate, Scott McClellen. Though Wayne provided a shining beacon for victims of spinal injuries, he faced one more challenge in 1986 when he was diagnosed with cancer. After battling illness for several months, he died at age 34 on January 4, 1987, at his home in Ocala, Florida. As he’d indicated on his college application, he did truly “commit all things to His leadership.” Wayne’s football coach at Wheaton College, Gary Taylor, observed at the funeral, “He taught us about courage because he faced unbelievable odds and time and again beat them…He set goals, saying, ‘If I can only get by today, then I can start on tomorrow.'”

A memorial scholarship in Wayne’s honor was established at Wheaton College to recognize, encourage and financially assist any upperclass student who has faced, or is facing, personal adversity, and who nevertheless shows continued growth in faith, in academic performance and in contribution to campus life.

Give me the harp I hear…

Shortly after the death of seven-month old Jonathan Edwards Blanchard in Cincinnati another child was conceived by Jonathan and Mary Blanchard. Born on January 7, 1841, Mary Avery Blanchard entered life on her mother’s birthday and was so named for her. The eldest of the Blanchard children, Jonathan and Mary sought to provide the best educational opportunities for Mary Avery. For a summer she lived with the John Payson Willistons and enrolled in school in Northampton, Massachusetts. While in school Jonathan wrote his daughter encouraging her to not worry about her grade level but whether she was thorough in her work. When she wrote back in one letter about the handsome men Jonathan wrote back and said she was there to study. Displaying his beliefs about the education of women Jonathan had Mary Avery studying Greek, so that she may read the New Testament, Latin and Mathematics. He told her that “Latin was a glorious language of a glorious people….Love it.” When Mary Avery returned to Galesburg she finished her studies at Knox Female Seminary and became a school teacher in Prospect City, Illinois for a time. When she was seventeen she enrolled at Mount Holyoke College. Jonathan expected much of his eldest child. She had the same impetuous spirit as her father. Engaged for a time to a Mr. Caldwell, someone that Jonathan believed to be less than pious, Mary Avery snapped back that she would marry him and they would go to hell together. However, before they could wed Mary Avery contracted consumption, known today as tuberculosis. Though she was able to make the move to Wheaton with the family when Jonathan assumed the presidency of Wheaton College, Mary Avery died on December 6, 1860, a month before her twentieth birthday. This was the fourth child that Jonathan and Mary Blanchard had lost before reaching full adulthood. Enamored with the work of John G. Fee, Mary Avery bequeathed what little worldly goods she had to his work at Berea College in Kentucky.

Shortly after the death of seven-month old Jonathan Edwards Blanchard in Cincinnati another child was conceived by Jonathan and Mary Blanchard. Born on January 7, 1841, Mary Avery Blanchard entered life on her mother’s birthday and was so named for her. The eldest of the Blanchard children, Jonathan and Mary sought to provide the best educational opportunities for Mary Avery. For a summer she lived with the John Payson Willistons and enrolled in school in Northampton, Massachusetts. While in school Jonathan wrote his daughter encouraging her to not worry about her grade level but whether she was thorough in her work. When she wrote back in one letter about the handsome men Jonathan wrote back and said she was there to study. Displaying his beliefs about the education of women Jonathan had Mary Avery studying Greek, so that she may read the New Testament, Latin and Mathematics. He told her that “Latin was a glorious language of a glorious people….Love it.” When Mary Avery returned to Galesburg she finished her studies at Knox Female Seminary and became a school teacher in Prospect City, Illinois for a time. When she was seventeen she enrolled at Mount Holyoke College. Jonathan expected much of his eldest child. She had the same impetuous spirit as her father. Engaged for a time to a Mr. Caldwell, someone that Jonathan believed to be less than pious, Mary Avery snapped back that she would marry him and they would go to hell together. However, before they could wed Mary Avery contracted consumption, known today as tuberculosis. Though she was able to make the move to Wheaton with the family when Jonathan assumed the presidency of Wheaton College, Mary Avery died on December 6, 1860, a month before her twentieth birthday. This was the fourth child that Jonathan and Mary Blanchard had lost before reaching full adulthood. Enamored with the work of John G. Fee, Mary Avery bequeathed what little worldly goods she had to his work at Berea College in Kentucky.

Upon Mary Avery’s death M. F. Bigney, editor of the the New Orleans paper, The Daily City Item, wrote

Give Me The Harp. She was known as a pious girl and these words were based upon her final earthly words, “Give me the harp I hear.” The poem appeared in Bigney’s The Forest Pilgrims, and other poems published in 1867.

Give me the harp with the sounding strings,

The harp whose tones I hear–

It seems upborne by an angel’s wings,

And unto my bursting heart it brings

The sounds of hope and cheer–

A melody all divine, that springs

From a higher and purer sphere.

Give me the harp, and this trembling hand

Released from the ills of earth,

Shall learn the lays of the better land,

Shall touch the strings with a high command,

And the joy of a spirit-birth

Shall thrill my soul with a rapture grand,

With a fond and holy mirth.

Give me the harp, and I’ll bid farewell

To the fleeting scenes of time ;

With the loved ones gone before I’d dwell,

My harp with theirs should the echoes swell

Of a high immortal rhyme ;

Give me the harp, for I fain would tell

Of release from this world of crime.

Truth Unchanged, Unchanging…

Dr. Iain Murray, biographer of Dr. D.M. Lloyd-Jones, pastor of Westminster Chapel in London, writes of the famed Reformed theologian’s visit to the campus of Wheaton College:

On Monday, August 11, the Lloyd-Joneses left Toronto for Wheaton College (near Chicago) where Carl F.H. Henry had asked ML-J to give the first series of Jonathan Blanchard Lectures on a subject related to apologetics. The result was five addresses subsequently published as Truth Unchanged, Unchanging. In essence they were an explanation of his whole approach to evangelism: the modern secular scene requires no new apologetic because man’s condition in sin is the same as it always has been; only the Bible can explain that condition and only the gospel provides a remedy radical enough for the problem. One relaxation in the heat wave which overtook them at Wheaton was an outing to the farm of some Welsh relatives in Illinois. After writing to his mother with news of the relatives, ML-J had to add something on his special interest: “They certainly have some wonderful ponies. Unfortunately it was too hot for us to see any of them in motion.”

Lloyd-Jones’ five Blanchard lectures, collectively titled “Sin: Its Diagnosis and Treatment,” eventually comprised Truth Unchanged, Unchanging (1951), which was his first post-war book to be printed. The ongoing lecture series, sponsored by the Alumni Association, was intended to be primarily apologetic and academic in emphasis rather than devotional. The conservative Welsh preacher was the successor to G. Campbell Morgan, the “Prince of Expositors,” at Westminster Chapel. Lloyd-Jones died in 1981.

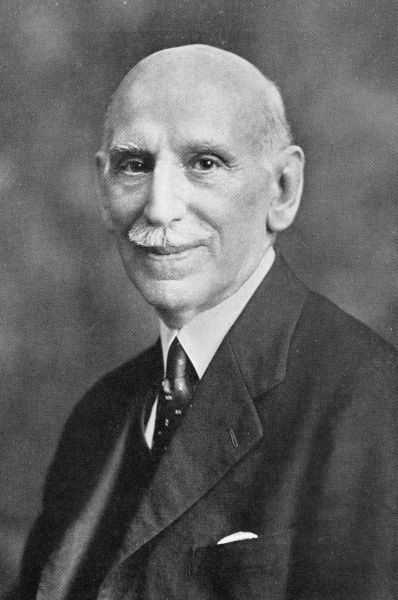

Evan Welsh on the Wheaton College Presidents

Dr. Evan Welsh, Wheaton’s first chaplain, serving from 1955-70, and later as Alumni Chaplain, sat for this excerpted 1980 interview, conducted by Mark Dawson, for the Record. The 75-year-old preacher briefly recounts the Wheaton College presidents he has known.

Dr. Evan Welsh, Wheaton’s first chaplain, serving from 1955-70, and later as Alumni Chaplain, sat for this excerpted 1980 interview, conducted by Mark Dawson, for the Record. The 75-year-old preacher briefly recounts the Wheaton College presidents he has known.

“He was one of the most striking-looking men that ever lived,” Welsh recalled of Charles Blanchard. “He was about six-two, well built, had snowy white hair, a snowy mustache, and piercing black eyes. But he was very gentle, very loving, very firm, very courageous. He treated the college like his family. He had deep convictions on salvation, holy living and the Law of God.” Welsh said that late in his career, Blanchard insisted that Wheaton maintain its doctrinal integrity in the face of rising modernism in the evangelical world. Even so, in the 1920s evangelicalism began to shift away from the ideals of the Blanchards. “Churches became prophetic centers,” Welsh said. “I remember in chapel in 1925, an outstanding speaker telling us that it looked like 1926 was surely the day of the Lord’s coming. They were so preoccupied with eschatology that they neglected the social aspect of the gospel that had been big in (Jonathan) Blanchard’s day.”

With the sudden death of Charles Blanchard in 1925, the college invited J. Oliver Buswell to take the presidency. Describing Buswell as “an excellent scholar, a strong speaker and a great theologian,” he added that Buswell was committed to being separated from the old-line denominations. Welsh praised Buswell for getting Wheaton accredited in spite of hostility from secular educators because of the college’s evangelical stance. He also complimented Buswell for his doctrinal convictions, his emphasis on good scholarship, and for doubling the student population. According to Welsh, Buswell introduced the pledge to assure the Christians of his day that Wheaton would not “go down the drain” once the Blanchards were gone. “We had no pledge in my day,” he said. “Although President Blanchard believed strongly in the separated life.” Welsh spoke highly of Buswell, but said his differences with the trustees of his support of an independent missions board and of a controversial football coach led him to resign.

“Dr. Edman was just the man to take the presidency at that time,” Welsh continued. “In the midst of the fundamentalist-modernist controversy, here comes Ray Edman, a very pacifistic soul, a fine, devout Christian. He was a marvelous P.R. man. In any group he just won their hearts. I think how many times he’d say, ‘Evan, your caffeine count is low, let’s go out for a cup of coffee.’ He was a very genial, warm person, a keen mind, a good administrative hand at the helm, and a fervent spirit.”

Likewise, Welsh described Dr. Armerding as a spiritual giant. “I have seen him grow on the job,” he said. “He was less of a mixer with students than Dr. Edman when he took the presidency, but that has changed over the years.” Citing an example, Welsh described a chapel service in the 1960s. “He gave the chapel talk, and then he said, ‘Now before I close this chapel, there’s another part to it that’s going to come as a complete surprise even to the other party involved. Will Jerry Lower please come forward?’ This surprised hippie-type person – I can hardly tell this without tears – came forward. Then Dr. Armerding just threw his arms around him. Well, the chapel went wild.” Welsh paused, drying his eyes with his hands. “Do you think I’ve communicated my feeling about Wheaton, guy?” Welsh said his love for Wheaton centers around its biblical basis, its strong scholarship, and its social passion. “I sometimes say to my wife, we’ve been privileged to know some of the best people in the world.”

“For the glory of God and my neighbor’s good”

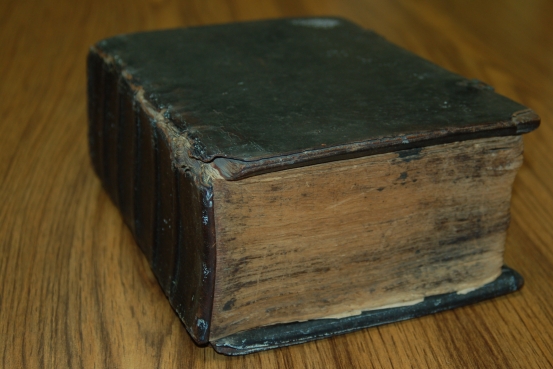

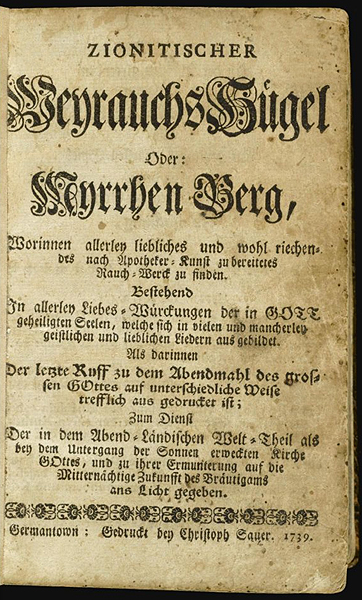

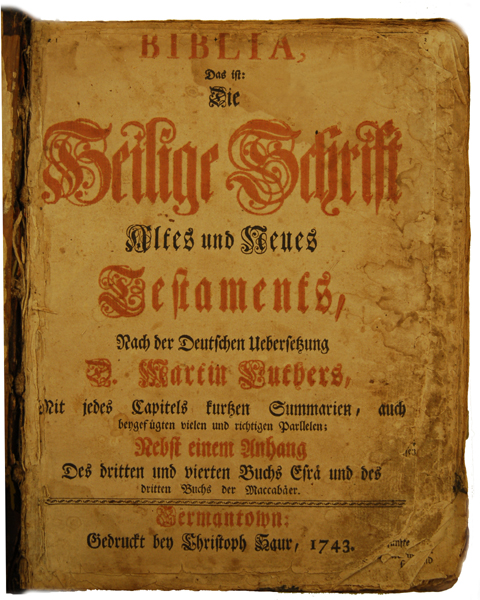

One would think that Wheaton College would have one of the best bible collections around–at least among small colleges. Unfortunately, this is not the case. However, over time and through purchasing and gifts it is possible for Wheaton expand its current holdings. One way in which the Archives & Special Collections has expanded its holding is through the acquisition of several collections that had been a part of the holdings of the Billy Graham Center Museum and Library. One such gem that came via the museum was a copy the first bible printed in America in an European language (German). A later edition of this bible became known as the “gun-wad bible” because during the Battle of Germantown (1777) during the American Revolution British soldiers broke into the printer’s shop and confiscated thousands of pages of the yet completed bibles and used them for gun-wadding.

Christopher Sauer, born Johann Christoph Sauer in 1695, sailed to America with his wife and young son in 1724 and nearly fifteen years later had established a thriving printing business. Historians have recognized Christopher Sauer (also known to history as Johann Christoph Sauer, Christoph Saur, Christoph Sauer and Christopher Sower) as one of the most important figures of colonial Pennsylvania. Sauer was known as a separatist and did not seem to be a part of any particular religious community, though his wife had moved to the Ephrata commune near Germantown, leaving the senior and junior Christoph.

In 1743 Saur printed the first European-language Bible printed in America. The only bible printed in America prior to this was John Eliot’s Algonquin Bible (1663). Sauer’s bible was a huge undertaking and became a 1267 page volume. This is considered one of the largest printing ventures in America at the time. Eventually the 1200 copies printed were sold. Though he was a business man he made it known that those who were poor and could not afford his bible could ask to receive one. Sauer’s son eventually printed a second edition in 1763 and a third in 1776 (mentioned above) — all before Robert Aitken’s “Congress Bible” of 1782.

As would reflect the future nature of American religion, Sauer’s bible created controversy and division even before it was finished. Area Lutheran and Reformed clergy feared the translation chosen, Berleberg’s, along with some of the printing’s typographical errors would confusion readers and encourage heresy. Sauer did not help his situation by using multiple translations in a single book (Job). Despite the pressure Sauer pressed on.

To date about two hundred of Sauer’s publications have been identified. His press, which he built himself, was quite active and produced a steady stream of devotional and theological works. Some of the earliest hymnals for German speakers came from Sauer’s press. In fact the first publication off of his press was a hymnal that was reprinted over and over again. The type was sent to him from Germany by Christopher Shutz. Sauer was well-acquainted with revivalist George Whitefield and had hopes of printing devotional and theological works in English, including a quarto-sized bible, but the high cost of paper proved a hurdle too great.

To date about two hundred of Sauer’s publications have been identified. His press, which he built himself, was quite active and produced a steady stream of devotional and theological works. Some of the earliest hymnals for German speakers came from Sauer’s press. In fact the first publication off of his press was a hymnal that was reprinted over and over again. The type was sent to him from Germany by Christopher Shutz. Sauer was well-acquainted with revivalist George Whitefield and had hopes of printing devotional and theological works in English, including a quarto-sized bible, but the high cost of paper proved a hurdle too great.

His motto for his press was “For the glory of God and my neighbor’s good.” Sauer wrote to a patron in September, 1740, that “I would rather serve my neighbor and glorify God in that way than to gather a large earthly fortune for myself or for my son….” He continued, saying, “that nothing shall be printed except that which is to the glory of God and for the physical or eternal good of my neighbors. What ever does not meet this standard, I will not print. I have already rejected several, and would rather have the press standing idle. I am happier when I can distribute something of value among the people for a small price, than if I had a large profit without a good conscience.” He was known for his charitable works, so much so that he was known as “Bread Father” and the “Good Samaritan” of Germantown. It is said that he would meet German immigrants as they arrived on ships provide hospitality to the sick and needy.

Sauer did what he could to expand his work and to make his publications affordable. He had heard of a printer in Philadelphia that claimed knowing the formula for a better ink and Sauer inquired about learning the formula. Asking what the printer would ask in return for teaching Sauer the printer asked Sauer to build him a press like his own. Saying he would consider the trade Sauer later thought to myself, “You have carried on twenty-six trades and crafts without any teacher, and made almost all of the tools necessary for them. Why should you now pay so dearly for this knowledge?” The next morning he had an idea on how to make the a new ink. The ink was as good and even cheaper than the old.

Sauer did what he could to expand his work and to make his publications affordable. He had heard of a printer in Philadelphia that claimed knowing the formula for a better ink and Sauer inquired about learning the formula. Asking what the printer would ask in return for teaching Sauer the printer asked Sauer to build him a press like his own. Saying he would consider the trade Sauer later thought to myself, “You have carried on twenty-six trades and crafts without any teacher, and made almost all of the tools necessary for them. Why should you now pay so dearly for this knowledge?” The next morning he had an idea on how to make the a new ink. The ink was as good and even cheaper than the old.

Christopher Sauer died on September 25, 1758, after a remarkable career in America. During his thirty-four years in America his press operation and intellectual interests put him at the forefront of many of the important controversial political and theological issues of his day. About one fifth of the publications of his press were translations or reprints of European books, largely theological or devotional in nature. These productions helped to maintain America’s European ties. Conversely, many of Sauer’s American works were reprinted in Europe, bringing ideas from the New World to the Old.

This entry in indebted to Donald Durnbaugh’s wonderful article on Sauer.

[Durnbaugh, Donald F. “Christopher Sauer Pennsylvania-German Printer: His Youth in Germany and Later Relationships with Europe.” The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography, Vol. 82, No. 3 (Jul., 1958), pp. 316-340.]

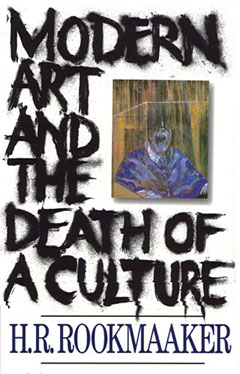

Rookmaaker & Modern Art…40 years later

This year marks the 40th anniversary of Hans Rookmaaker’s classic, Modern Art and the Death of a Culture. In his groundbreaking work, Rookmaaker offers pointed perspectives on the counter-cultural turmoil of the 1960s as reflected in its art. He examines histories, themes and reactions in classic and contemporary creative endeavor; and urgently calls Christian artists to bold commitment in executing their unique roles as prophets and messengers. He was impatient with naive questions or lazy, unfocused thinking. Church audiences who blithely dismissed modern art received a not-so-gentle chide: “How can you say that modern art is ugly when you worship the Lord in a building painted like this?” In talks and writing, Hans Rookmaaker sought to address the disastrous severance of truth and beauty from divine revelation. He argued that there is no true beauty divorced from truth, love and freedom, either in art or life. “We are Christians whether we sleep, eat or work hard,” he writes in Art Needs No Justification (1978), “whatever we do, we do it as God’s children.”

This year marks the 40th anniversary of Hans Rookmaaker’s classic, Modern Art and the Death of a Culture. In his groundbreaking work, Rookmaaker offers pointed perspectives on the counter-cultural turmoil of the 1960s as reflected in its art. He examines histories, themes and reactions in classic and contemporary creative endeavor; and urgently calls Christian artists to bold commitment in executing their unique roles as prophets and messengers. He was impatient with naive questions or lazy, unfocused thinking. Church audiences who blithely dismissed modern art received a not-so-gentle chide: “How can you say that modern art is ugly when you worship the Lord in a building painted like this?” In talks and writing, Hans Rookmaaker sought to address the disastrous severance of truth and beauty from divine revelation. He argued that there is no true beauty divorced from truth, love and freedom, either in art or life. “We are Christians whether we sleep, eat or work hard,” he writes in Art Needs No Justification (1978), “whatever we do, we do it as God’s children.”

Henderik “Hans” Roelof Rookmaaker, art historian, professor, author and lecturer, was born in 1922 in the Netherlands and spent his early years living in Sumatra (Indonesia). After returning to Holland in 1933, Hans developed a lifelong passion for jazz music. Following the German Occupation in 1940, Hans was interned for distributing anti-Nazi leaflets. After World War II, Rookmaaker moved to Amsterdam and studied art history, integrating philosophy with Christian doctrine. He authored many books pertaining to art theory, art history and music. Lecturing throughout the 1960s and ’70s on university campuses and conferences in the U.S. and U.K., he endeared himself to a generation of questioning students. The Papers of Hans Rookmaaker are available to researchers in the college’s Archives & Special Collections.

Henderik “Hans” Roelof Rookmaaker, art historian, professor, author and lecturer, was born in 1922 in the Netherlands and spent his early years living in Sumatra (Indonesia). After returning to Holland in 1933, Hans developed a lifelong passion for jazz music. Following the German Occupation in 1940, Hans was interned for distributing anti-Nazi leaflets. After World War II, Rookmaaker moved to Amsterdam and studied art history, integrating philosophy with Christian doctrine. He authored many books pertaining to art theory, art history and music. Lecturing throughout the 1960s and ’70s on university campuses and conferences in the U.S. and U.K., he endeared himself to a generation of questioning students. The Papers of Hans Rookmaaker are available to researchers in the college’s Archives & Special Collections.

Low Degrees and Frost

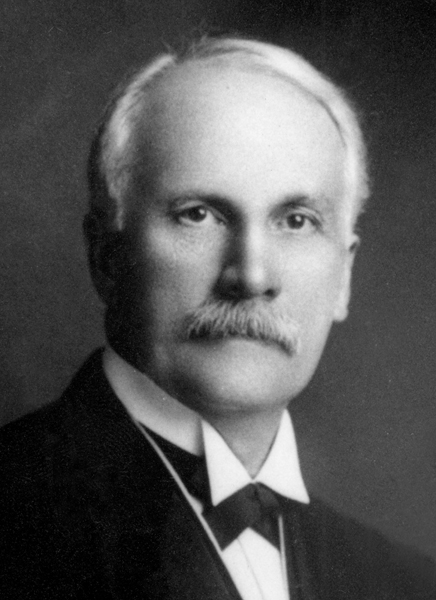

Wheaton College has issued several honorary degrees throughout the years. Seldom, perhaps, has it offered the tempting potentiality of receiving one, as in the case of Henry W. Frost, Home Director for North America of the China Inland Mission (now called Overseas Missionary Fellowship), founded by Hudson Taylor.  In the following exchange, Frost gently prods a somewhat distracted Dr. Charles A. Blanchard, second president of Wheaton College, toward remembering a past communication.

In the following exchange, Frost gently prods a somewhat distracted Dr. Charles A. Blanchard, second president of Wheaton College, toward remembering a past communication.

May 12, 1921

Dear Dr. Blanchard,

You will recall the fact that I was corresponding with you about a year ago about the possibility of my receiving from the college a B.A. degree. I have hoped to hear from you in regard to the matter but have not done so. Thinking you may have written and that your letter has gone astray, I beg to enquire whether or not the faculty reached any conclusion in the matter. I am sorry to trouble you about what concerns myself, rather than the interests of the college, but I shall be grateful for a few lines giving your decision. May I add, if you can grant me the degree, that it will have real value in the Lord’s service, especially now that I am living in Princeton, where such an honor is held in much esteem. It has been a pleasure to get better acquainted with you of late…

With warm regards, I am, yours faithfully,

Henry W. Frost

Though this is a somewhat pressing matter for Frost’s late-life phase of ministry, Blanchard seems to have relegated it to a lower priority:

May 18, 1921

My dear brother,

In this busy life, with so many things crowding upon me, I am sorry to say I forgot many things I wish I could remember. I had entirely lost sight of the matter about which you wrote me. I am afraid you sent me some information about your educational history which I have mislaid and forgotten. Supposing you tell me again. I know of your relations to the China Inland Mission and I approve of them thoroughly. I need, however, in stating the case to my fellow workers, to know all the facts that I may answer the questions which they are certain to ask.

With best regards, and wishing you every blessing, I am faithfully yours,

Charles A. Blanchard

Frost patiently reiterates his predicament:

May 23, 1921

Dear Dr. Blanchard,

Your most kind letter of the 18th was duly received upon the 21st. I beg to thank you for it and for the generous sympathy which it expresses. In answer to your question about our past correspondence, allow me to reply as follows: About a year ago I asked you if I could pursue with you an extra muros course of study which would lead to my securing a B.A. degree.  You answered that Wheaton had no such arrangement, but you said, if I would give you the facts of the case, that the faculty might grant me an honorary degree. I then explained that I had been a student at Princeton, in the class of ’80; that I had taken and passed my examinations for the first two years; that I had continued in spite of poor health, through the third year, taking some examinations but not all; and that sickness had prevented my continuing through the fourth year; that I had could not make up what was lacking in Princeton in view of the fact that a regular attendance of classes was required and my busy life forbade my attempting this; and finally, that I desired a degree for two reasons, first, that I might be more in touch with University men, and second and particularly, that being more closely connected with them I might be the more used of the Lord in their behalf. Following this, you asked for the names of two individuals to whom you might write concerning me and whose letters you might present to the faculty. I then gave you the names of the Rev. Charles R. Erdman, D.D., professor in the seminary here and Rev. T.R. O’Meara, D.D., Principal of Wycliffe College, Toronto. As Dr. O’Meara recently asked me if I had heard from you, I know that you wrote to him and that he replied, and I presume the same is true in respect to Dr. Erdman. I should have refrained from writing again to you about so personal and apparently selfish a matter had it not been for the fact that settling at Princeton, where college degrees are so much valued, has emphasized my need of being in rapport with those about me. I am anxious to be used of God here as largely as possible and I am assured that having a degree will much increase my usefulness. Thanking you for anything you may do in my behalf and assuring you of my warm regards,

You answered that Wheaton had no such arrangement, but you said, if I would give you the facts of the case, that the faculty might grant me an honorary degree. I then explained that I had been a student at Princeton, in the class of ’80; that I had taken and passed my examinations for the first two years; that I had continued in spite of poor health, through the third year, taking some examinations but not all; and that sickness had prevented my continuing through the fourth year; that I had could not make up what was lacking in Princeton in view of the fact that a regular attendance of classes was required and my busy life forbade my attempting this; and finally, that I desired a degree for two reasons, first, that I might be more in touch with University men, and second and particularly, that being more closely connected with them I might be the more used of the Lord in their behalf. Following this, you asked for the names of two individuals to whom you might write concerning me and whose letters you might present to the faculty. I then gave you the names of the Rev. Charles R. Erdman, D.D., professor in the seminary here and Rev. T.R. O’Meara, D.D., Principal of Wycliffe College, Toronto. As Dr. O’Meara recently asked me if I had heard from you, I know that you wrote to him and that he replied, and I presume the same is true in respect to Dr. Erdman. I should have refrained from writing again to you about so personal and apparently selfish a matter had it not been for the fact that settling at Princeton, where college degrees are so much valued, has emphasized my need of being in rapport with those about me. I am anxious to be used of God here as largely as possible and I am assured that having a degree will much increase my usefulness. Thanking you for anything you may do in my behalf and assuring you of my warm regards,

I am, yours very faithfully,

Henry W. Frost

Blanchard at last dedicates attention to the Frost affair and it appears that resolution is near:

May 26, 1921

My dear brother: I have just returned after an absence of some days and have been in my office very little for quite a while. This must be my partial apology for tardiness in writing. I hope to be at home now for some days and I will try to take up the matter concerning which you have written to me, at once.

With best regards, I am, sincerely yours,

Charles A. Blanchard

The remainder of the exchange is not extant. Evidently, Frost seems to have been denied his request, as he is not cited among Wheaton College’s honorary degree recipients. This responsibility fell to another institution. According to his biography, “By Faith”: Henry W. Frost and the China Inland Mission by Dr. and Mrs. Howard Taylor, he was in 1929 conferred an honorary Doctor of Divinity by Westminster College, representing the United Presbyterian denomination, “…in recognition of his contribution to Christian life and literature…”

Rediscovering Values – Jim Wallis

![]() Jim Wallis was recently on Wheaton’s campus as part of an informal debate with Arthur Brooks on the topic “Does Capitalism Have a Soul?” The debate was held in Edman Chapel and also featured Arthur C. Brooks of the American Enterprise Institute and moderator, Michael Gerson (Washington Post columnist and former speechwriter and senior adviser to George W. Bush)..

Jim Wallis was recently on Wheaton’s campus as part of an informal debate with Arthur Brooks on the topic “Does Capitalism Have a Soul?” The debate was held in Edman Chapel and also featured Arthur C. Brooks of the American Enterprise Institute and moderator, Michael Gerson (Washington Post columnist and former speechwriter and senior adviser to George W. Bush)..

Wallis is president and CEO of Sojourners, a bestselling author, public theologian, speaker, and international commentator on ethics and public life. He has been named to serve on the White House Advisory Council on Faith-based and Neighborhood Partnerships. His latest book, Rediscovering Values: On Wall Street, Main Street, and Your Street–A Moral Compass for the New Economy was released in January 2010 (paperback, early 2011). His two previous books, The Great Awakening: Reviving Faith & Politics in a Post-Religious Right America and God’s Politics: Why the Right Gets It Wrong and the Left Doesn’t Get It, were both New York Times bestsellers. Wallis discusses his reasons for writing Rediscovering Values in an article from the Huffington Post. The Papers of Jim Wallis as well as Sojourners are available to researchers in the college’s Archives & Special Collections.

the White House Advisory Council on Faith-based and Neighborhood Partnerships. His latest book, Rediscovering Values: On Wall Street, Main Street, and Your Street–A Moral Compass for the New Economy was released in January 2010 (paperback, early 2011). His two previous books, The Great Awakening: Reviving Faith & Politics in a Post-Religious Right America and God’s Politics: Why the Right Gets It Wrong and the Left Doesn’t Get It, were both New York Times bestsellers. Wallis discusses his reasons for writing Rediscovering Values in an article from the Huffington Post. The Papers of Jim Wallis as well as Sojourners are available to researchers in the college’s Archives & Special Collections.