In recent months, former Indiana Senator and Congressman Dan Coats, announced his intentions to challenge the senate seat of Indiana Democrat Evan Bayh in the November 2010 mid-term elections. Coats is a 1965 graduate of Wheaton College and currently serves on the institution’s Board of Trustees. [Updated: Dan Coats was elected to the U.S. Senate in January 2011].

In recent months, former Indiana Senator and Congressman Dan Coats, announced his intentions to challenge the senate seat of Indiana Democrat Evan Bayh in the November 2010 mid-term elections. Coats is a 1965 graduate of Wheaton College and currently serves on the institution’s Board of Trustees. [Updated: Dan Coats was elected to the U.S. Senate in January 2011].

Below is a transcript of the May 17, 1992 undergraduate commencement address given at his alma mater on moral conflict and the limits to compromise. It was first published in Wheaton Alumni magazine (Fall 1992). An audio recording is available here.

————————————————–

Moral principles, in our tradition, are generally clear and unavoidable. We knock our heads against them with regularity. They are hard to follow, yet not hard to define. But some of the greatest agony I’ve known as a member of Congress has come when those clear, commanding moral precepts collide in conflict.

How do you make a decision between a better environment and the jobs it will cost? The dignity of employment and our stewardship over creation both demand moral attention. Is a cleaner river worth regulations that eliminate 30 jobs, 300 jobs, 3000 jobs? How do you weigh cleaner air against the broken spirit of the unemployed? How do you choose between fighting poverty and fighting dependency? How do you pursue generous compassion when it risks the slow destruction of the soul and spirit we see in generation after generation of a welfare underclass? How do you choose between a reverence for life, and the use of fetal tissue from existing abortions to treat the victims of Parkinson’s Disease? How do you provide hope to those who suffer, when it risks covering the horror of abortion with a veneer of scientific progress and public service?

This is not the politics of triumph and trumpets. It is the occupation of restless nights and troubled days. Sometimes every option is tainted by suffering and sin. Sometimes each alternative is made uncomfortable by a hybrid of good and evil. Sometimes we are left with the murky battle between bad and worse. This is not relativism. The principles themselves are clear and immutable. But in a fallen world, one is often set against the other. Stewardship against compassion. Generosity against independence. Respect for life against the suffering of the sick. It means something very personal for those who participate in these choices. No matter what decision is made, the outcome will cause doubt. It means loss of certainty and peace. It means mistakes, self-reproach, and guilt. It means scar tissue and calluses. You find that character sometimes consists of how you act on the second or third try. You find that integrity is a voyage, not a harbor. This, as they say, is the real world–with its fogs of morning and evening, and its sudden storms.

This is not the politics of triumph and trumpets. It is the occupation of restless nights and troubled days. Sometimes every option is tainted by suffering and sin. Sometimes each alternative is made uncomfortable by a hybrid of good and evil. Sometimes we are left with the murky battle between bad and worse. This is not relativism. The principles themselves are clear and immutable. But in a fallen world, one is often set against the other. Stewardship against compassion. Generosity against independence. Respect for life against the suffering of the sick. It means something very personal for those who participate in these choices. No matter what decision is made, the outcome will cause doubt. It means loss of certainty and peace. It means mistakes, self-reproach, and guilt. It means scar tissue and calluses. You find that character sometimes consists of how you act on the second or third try. You find that integrity is a voyage, not a harbor. This, as they say, is the real world–with its fogs of morning and evening, and its sudden storms.

Sometimes the greatest enemy is paralysis. An odd courage is needed to choose when a choice is torn by moral conflict–to walk in an unfamiliar land without landmarks. After the facts are collected, after the principles are defined, after the prayers are offered, a decision is required. Those who make them carefully are left drained of self- righteousness. Moral choice begins with surrender. It completes itself in humility. You begin to understand, with Dietrich Bonhoeffer, “It is not Christian men who shape the world with their ideas, but it is Christ who shapes men in conformity with Himself.” The response of some is to withdraw and separate. They have my respect, but not my agreement. Men and women were not made for safety. It has been said that the fullness of life is in the hazards of life. And, even in our worst failure, we experience the powerful alchemy of the resurrection, which turns defeat into victory.

I am not a theologian. But I sometimes suspect that this is what Martin Luther meant when he urged, “Sin boldly.” We must have the courage to act in uncertainty–even with tainted options. It is the unavoidable burden of freedom in a fallen world. As G.K. Chesterton said, “Even a bad shot is dignified when he accepts a duel…If a thing is worth doing, it is worth doing badly.” So far, much of the world would nod in agreement about conflicted moral choices. Many already use the fact as an excuse for self-serving compromise. Many don’t really want a struggle, they want an alibi. But there is something more to say. When we strip away the years of uncertain decisions; when we peel away the regrets and mistakes and scars, layer by layer; hopefully, we finally discover a core where we keep ourselves. Everything we eventually become is a shadow cast by its shape.

Thomas More is a hero of mine. We like to remember More as a man of unshakeable principle–even unto death. But as a politician and churchman under Henry VIII, he was a model of realism. He maneuvered effectively within the hounds of his principles. He possessed no trait of the fanatic. He was prudent and careful and subtle. But when the King required him to break his oath to his Church and forfeit a portion of his soul, the place where he kept himself was exposed. And it was harder than iron. In Robert Bolt’s play, A Man for All Seasons, More says, “When a man takes an oath, he’s holding his own self in his own hands, like water, and if he opens his fingers then he needn’t hope to find himself again.” The silent veto of conscience allowed him no more room for maneuver. And he lost his head on the scaffold–cheerfully, we are told by history. He died to prove he was not already dead. Bolt explains, “He knew where he left off, what area of himself he could yield to the encroachments of his enemies … but at length he was asked to retreat from that final area where he located himself. And then this supple, humorous, unassuming and sophisticated person set like metal, was overtaken by an absolutely primitive rigor, and could no more he budged than a cliff.” Like More…

Thomas More is a hero of mine. We like to remember More as a man of unshakeable principle–even unto death. But as a politician and churchman under Henry VIII, he was a model of realism. He maneuvered effectively within the hounds of his principles. He possessed no trait of the fanatic. He was prudent and careful and subtle. But when the King required him to break his oath to his Church and forfeit a portion of his soul, the place where he kept himself was exposed. And it was harder than iron. In Robert Bolt’s play, A Man for All Seasons, More says, “When a man takes an oath, he’s holding his own self in his own hands, like water, and if he opens his fingers then he needn’t hope to find himself again.” The silent veto of conscience allowed him no more room for maneuver. And he lost his head on the scaffold–cheerfully, we are told by history. He died to prove he was not already dead. Bolt explains, “He knew where he left off, what area of himself he could yield to the encroachments of his enemies … but at length he was asked to retreat from that final area where he located himself. And then this supple, humorous, unassuming and sophisticated person set like metal, was overtaken by an absolutely primitive rigor, and could no more he budged than a cliff.” Like More…

- We are called to an obedience that is easily misunderstood.

- We are asked to be hard where the world is soft.

- We are soft where the world is hard.

- We call homosexuality, for example, by its proper name: sin. But we must comfort AIDS patients with our love and our touch.

- We speak for moral absolutes: unchanging, eternal–but we have a particular call to accept and care for the morally spent.

- Where the world wants velvet, there is steel.

- Where it expects thunder, there is unspeakable peace.

This is often resented by a world that burns the wheat and gathers the chaff. An individual with a core of belief is strange by its standards–particularly a belief that someone will willingly die for. In every age, this kind of witness has broken the back of predictable human history. And it raises questions that you will need to answer.

Where do you locate that core of the self which cannot he moved? What wouldn’t you trade in a world of barter? What are you sure enough to live for? What would you cheerfully die for? In what cause are you willing to make war against the whole world?

Convictions like these may lead you into conflict, even suffering. You may know a season of darkness. But it’s said that integrity is perishable in the hot, summer months of success. And it’s said that character, like a photograph, develops in darkness. Without an uncompromising core of the self, introspection is endless and useless. Men and women become captive to their own doubts. Confusion is their native land, And finally, they lose the ability to believe in anything–even in their courage. Our identity is something that can be squandered–when compromise reaches that area where we locate ourselves.

Finally, at the center, we are empty. And the echoes of lost integrity no longer even disturb our dreams. Men and women come to the core of the self by different paths. For some that path is easy–like a gift. For others it is hard–like a trial. But those who have abandoned the journey have already reached their destination. And it is despair. Our promise is not a life free from mistakes, doubt, and moral conflict. A fallen world means fallen choices. But there are limits to compromise, set at the boundaries of the soul. And there are times when even subtle men, careful men, practical men, must turn to unyielding iron.

.

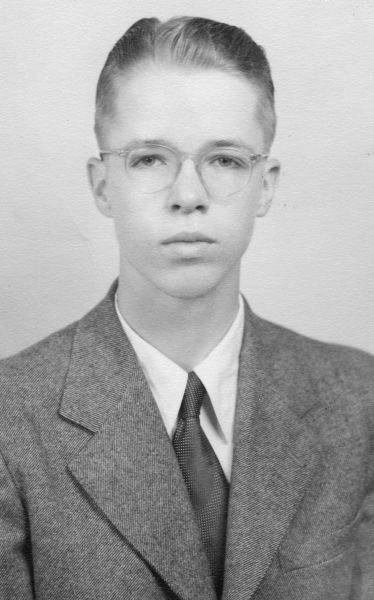

Wheaton College has provided intellectual incubation for many prominent theologians, professors and pastors. Surely one of the most brilliant was Zane Clark Hodges. Born in Washington, DC, but raised primarily in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, Hodges attended a Plymouth Brethren assembly with his parents and younger brother because there were no Baptist churches in town. Blessed with a sturdy intellect, he completed fifth and sixth grades in one year. During his high school junior year he became editor-in-chief of the student newspaper while participating in the Debating and Latin clubs. Reading widely, he also enjoyed comic books, which he collected, and played baseball. Hodges accepted Christ’s gift of eternal life at a meeting on the Greenwood Hills Bible Conference grounds in 1946. “Since that time,” he writes in his 1949 Wheaton College application, “I not only embrace the Lord Jesus as my Saviour, but also as the Son of God and the one who keeps me and is coming back, perhaps soon.” During this period he desired to enter the mission field as his life’s work. At college Hodges studied Greek, French and German, and further honed his analytical and oratorial skills with the Beltionian Literary society. The administration noted his poised, modest aspect, along with his industry and efficiency. As a result of his academic prowess he was inducted into the Honor Society. He was graduated in 1954, receiving his BA in Greek. Dr. Clarence Hale, Chairman of the Department of Foreign Languages, prophetically observes on Hodges’s placement form: “[He] is a young man of thoroughly reliable character and very high scholarship. He presents a neat appearance and meets people easily. He gives the promise of becoming a well-trained Bible teacher.” From Wheaton Hodges matriculated to Dallas Theological Seminary (DTS) where he acquired his Th.M. before joining its faculty as professor of New Testament Literature and Exegesis, remaining for 27 years until departing to pursue speaking and writing. Hodges produced commentaries on Hebrews, 1-3 John and James, in addition to writing articles for Bibliotheca Sacra, the scholarly journal for DTS. With Arthur Farstad he co-edited The Greek New Testament According to the Majority Text.

Wheaton College has provided intellectual incubation for many prominent theologians, professors and pastors. Surely one of the most brilliant was Zane Clark Hodges. Born in Washington, DC, but raised primarily in Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, Hodges attended a Plymouth Brethren assembly with his parents and younger brother because there were no Baptist churches in town. Blessed with a sturdy intellect, he completed fifth and sixth grades in one year. During his high school junior year he became editor-in-chief of the student newspaper while participating in the Debating and Latin clubs. Reading widely, he also enjoyed comic books, which he collected, and played baseball. Hodges accepted Christ’s gift of eternal life at a meeting on the Greenwood Hills Bible Conference grounds in 1946. “Since that time,” he writes in his 1949 Wheaton College application, “I not only embrace the Lord Jesus as my Saviour, but also as the Son of God and the one who keeps me and is coming back, perhaps soon.” During this period he desired to enter the mission field as his life’s work. At college Hodges studied Greek, French and German, and further honed his analytical and oratorial skills with the Beltionian Literary society. The administration noted his poised, modest aspect, along with his industry and efficiency. As a result of his academic prowess he was inducted into the Honor Society. He was graduated in 1954, receiving his BA in Greek. Dr. Clarence Hale, Chairman of the Department of Foreign Languages, prophetically observes on Hodges’s placement form: “[He] is a young man of thoroughly reliable character and very high scholarship. He presents a neat appearance and meets people easily. He gives the promise of becoming a well-trained Bible teacher.” From Wheaton Hodges matriculated to Dallas Theological Seminary (DTS) where he acquired his Th.M. before joining its faculty as professor of New Testament Literature and Exegesis, remaining for 27 years until departing to pursue speaking and writing. Hodges produced commentaries on Hebrews, 1-3 John and James, in addition to writing articles for Bibliotheca Sacra, the scholarly journal for DTS. With Arthur Farstad he co-edited The Greek New Testament According to the Majority Text.

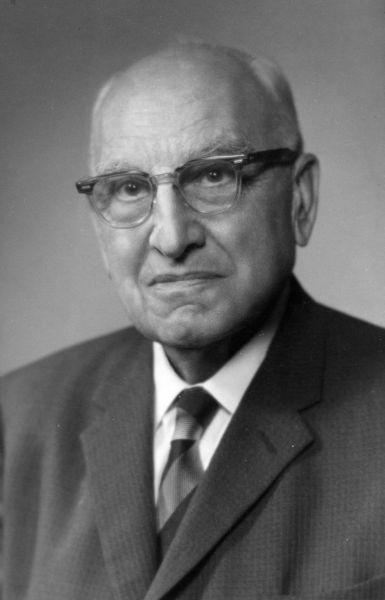

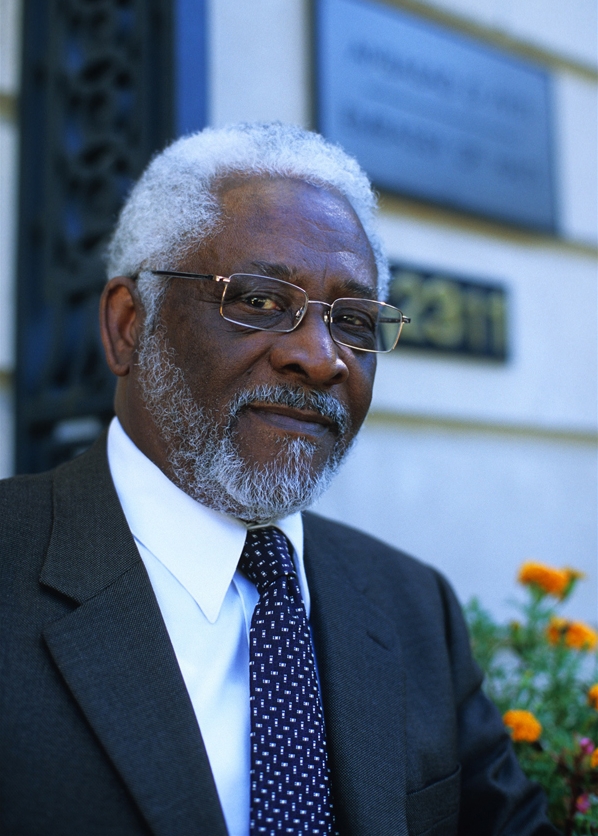

In recent weeks Raymond Joseph, as ambassador to the United States since March 2004, has been the international face of Haiti and the tremendous struggles that his impoverished nation has gone through since the earthquake of mid-January. He, like many of his fellow countrymen, has expressed a resiliency and a strong faith in God during harrowing times.

In recent weeks Raymond Joseph, as ambassador to the United States since March 2004, has been the international face of Haiti and the tremendous struggles that his impoverished nation has gone through since the earthquake of mid-January. He, like many of his fellow countrymen, has expressed a resiliency and a strong faith in God during harrowing times.