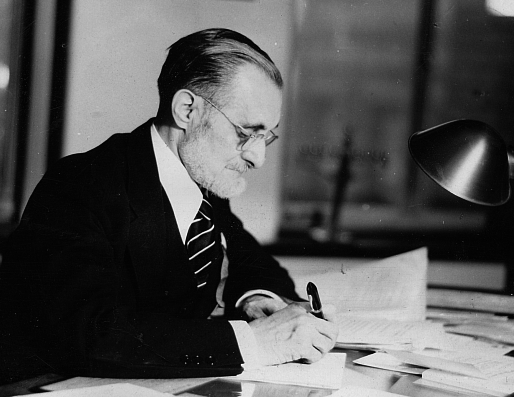

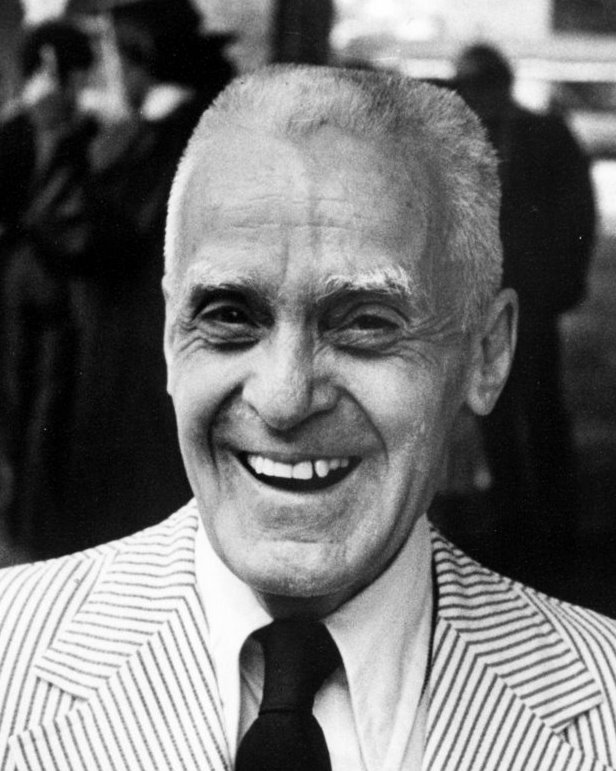

It is said that an institution is the lengthened shadow of a man. In a very real sense Dr. Thiessen, the first dean of our graduate school, left an indelible impression upon it…Though dead he yet speaketh. His influence continues through his writings and through the lives which he trained for God’s glad service.

So stated Dr. Enock Dyrness, Wheaton College registrar, eulogizing Dr. Henry Clarence Thiessen.

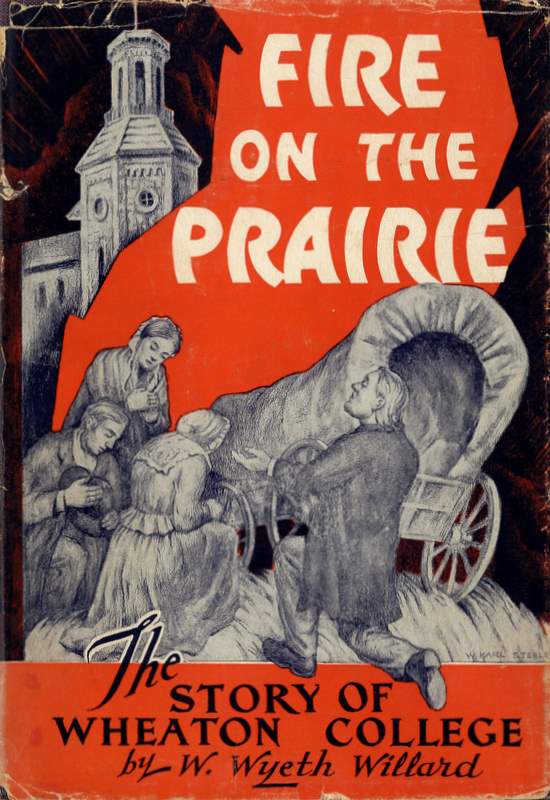

Born in 1883 in rural Nebraska, Thiessen accepted Christ at 17 and grew steadily in the scriptures as he also proclaimed the gospel to his friends. Thirsting for deeper scriptural knowledge, he entered the Bible Training School in Ft. Wayne, Indiana. After graduating he pastored for seven years in Ohio before accepting a call to teach full-time at the Bible Training School, where he also functioned as principal. Seeking further education, he entered Northern Baptist Theological Seminary, teaching part-time to pay expenses. From there he enrolled at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, then moved to Southern Baptist Theological Seminary for graduate studies, majoring in New Testament Greek. From there he served as Dean of the College of Theology at Evangel College in New Jersey. In 1931 Thiessen was hired by Dallas Theological Seminary, instructing New Testament Literature and Exegesis. He taught with distinction until 1935, when invited by Dr. J. Oliver Buswell to join the Wheaton College faculty. Responding with a letter to Buswell, Thiessen recounts his own impressive academic qualifications and that “…there may be a way of realizing my ideal at Wheaton College.” Specifically, this meant an ambition to establish “…a first class theological school of the fundamentalist and premillennial type in the North…” Once hired he started as Professor of Bible and Philosophy; a year later Buswell appointed him Chairman of the Bible and Theology Department. At this time, John Dickey, friend of the college, died, leaving an inheritance to be used expressly for instituting an advanced theological program within six months of his demise. As a result of this gift, Wheaton offered in 1937 its first graduate courses, headed by Thiessen. As the curriculum solidified and expanded, he chose Dr. Merrill Tenney as his associate.

Born in 1883 in rural Nebraska, Thiessen accepted Christ at 17 and grew steadily in the scriptures as he also proclaimed the gospel to his friends. Thirsting for deeper scriptural knowledge, he entered the Bible Training School in Ft. Wayne, Indiana. After graduating he pastored for seven years in Ohio before accepting a call to teach full-time at the Bible Training School, where he also functioned as principal. Seeking further education, he entered Northern Baptist Theological Seminary, teaching part-time to pay expenses. From there he enrolled at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, then moved to Southern Baptist Theological Seminary for graduate studies, majoring in New Testament Greek. From there he served as Dean of the College of Theology at Evangel College in New Jersey. In 1931 Thiessen was hired by Dallas Theological Seminary, instructing New Testament Literature and Exegesis. He taught with distinction until 1935, when invited by Dr. J. Oliver Buswell to join the Wheaton College faculty. Responding with a letter to Buswell, Thiessen recounts his own impressive academic qualifications and that “…there may be a way of realizing my ideal at Wheaton College.” Specifically, this meant an ambition to establish “…a first class theological school of the fundamentalist and premillennial type in the North…” Once hired he started as Professor of Bible and Philosophy; a year later Buswell appointed him Chairman of the Bible and Theology Department. At this time, John Dickey, friend of the college, died, leaving an inheritance to be used expressly for instituting an advanced theological program within six months of his demise. As a result of this gift, Wheaton offered in 1937 its first graduate courses, headed by Thiessen. As the curriculum solidified and expanded, he chose Dr. Merrill Tenney as his associate.

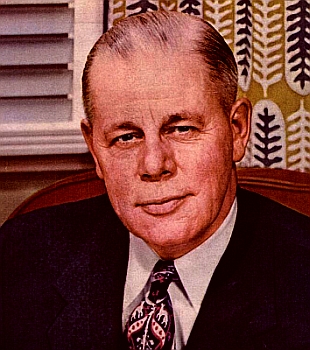

Thiessen was a popular but demanding instructor, firmly committed to dispensationalism. Sadly, this brought him into conflict with Dr. Gordon H. Clark, professor of philosophy and equally committed to Covenant theology. Wary of Clark’s “determinism,” Thiessen warned Buswell that his influence “…will do great, perhaps permanent, harm to many of the youngsters, because few of them are able to reply to his reasoning…” When V. Raymond Edman replaced Buswell as president in 1940, he followed Thiessen’s lead and took steps to dismiss Clark, first eliminating the philosophy major, then prohibiting Clark from teaching Reformed doctrine. Though Clark was tempted to leave, Buswell privately advised him to stay put. Edman then met with faculty and trustees to discuss Clark’s Calvinism and its “…chilling and harmful effect upon many students.”

Thiessen was a popular but demanding instructor, firmly committed to dispensationalism. Sadly, this brought him into conflict with Dr. Gordon H. Clark, professor of philosophy and equally committed to Covenant theology. Wary of Clark’s “determinism,” Thiessen warned Buswell that his influence “…will do great, perhaps permanent, harm to many of the youngsters, because few of them are able to reply to his reasoning…” When V. Raymond Edman replaced Buswell as president in 1940, he followed Thiessen’s lead and took steps to dismiss Clark, first eliminating the philosophy major, then prohibiting Clark from teaching Reformed doctrine. Though Clark was tempted to leave, Buswell privately advised him to stay put. Edman then met with faculty and trustees to discuss Clark’s Calvinism and its “…chilling and harmful effect upon many students.”

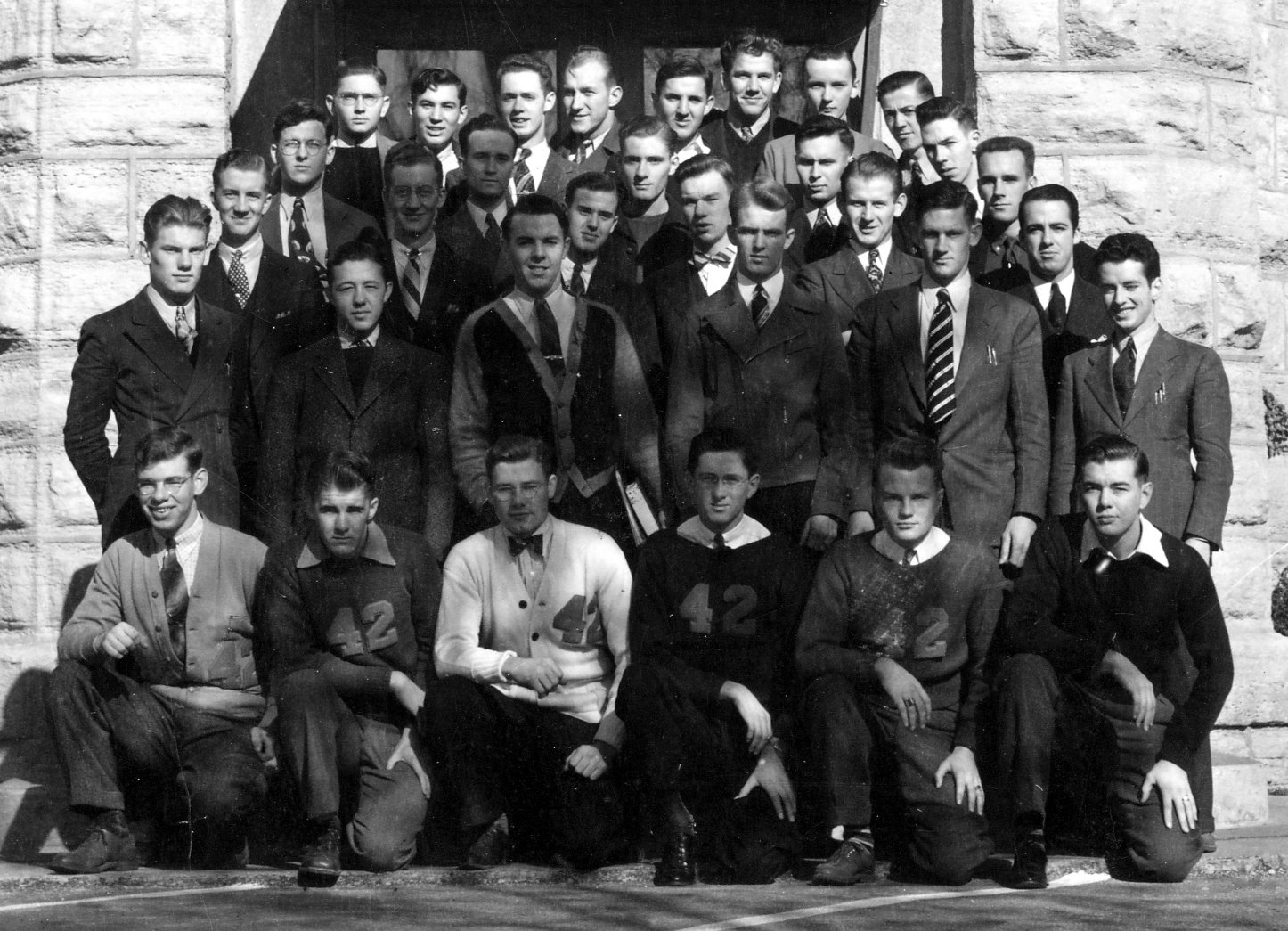

Clark was a supremely capable teacher of unquestioned piety, much-respected by his students, including young Ruth Bell (Graham) who, awash with the over-gushy pietism prevalent during those years, sought his refreshing “logic” and “…his unemotional brilliance…” Faced with intensifying hostility from the administration, Clark finally negotiated a technical resignation in 1942, moving on to a successful career at Butler University. After his firing, Edman reinstated the philosophy major but hired no trained philosophers to teach it, instead opting for theology professors to lead the course until Dr. Arthur Holmes revived the program in 1957.

Though the dispensationalists prevailed, they did not necessarily represent the position of all students or faculty. “Thiessenism,” wrote one, “is the only creed of Wheaton’s Bible Department…but a bitterly dogmatic and autocratic one…It’s agree with and memorize what Thiessen and his satellites say – or flunk…Of course, Dr. Clark isn’t the epitome of broad-mindedness – but he is [the epitome] of gentlemanly consideration…I’ve never found him forcing his views on anyone.” Premillennial dispensationalism remained Wheaton’s unofficial eschatological statement for the remainder of Edman’s tenure.

Though the dispensationalists prevailed, they did not necessarily represent the position of all students or faculty. “Thiessenism,” wrote one, “is the only creed of Wheaton’s Bible Department…but a bitterly dogmatic and autocratic one…It’s agree with and memorize what Thiessen and his satellites say – or flunk…Of course, Dr. Clark isn’t the epitome of broad-mindedness – but he is [the epitome] of gentlemanly consideration…I’ve never found him forcing his views on anyone.” Premillennial dispensationalism remained Wheaton’s unofficial eschatological statement for the remainder of Edman’s tenure.

Thiessen continued teaching at Wheaton College until debilitated by asthma, which allowed him only an hour or two of sleep each night. Advised by doctors to seek a warmer climate, he accepted in 1946 an invitation to serve as president and dean of Los Angeles Baptist Seminary, placing Wheaton’s Bible Department in Merrill Tenney’s capable hands. Thiessen preached his farewell sermon, titled “Facing the Future with Christ,” at Wheaton Bible Church. After moving to California his condition worsened as he endured numerous nasal operations, and on July 25, 1947, he died. His widow, Anna, requested that Thiessen’s brother complete and publish his classroom syllabus. Lectures in Systematic Theology, in print since 1949, steadfastly advances Dr. H.C. Thiessen’s hope that it might “…set forth the truth more clearly and logically, and that the Triune God, Father, Son and Holy Spirit will be glorified through its perusal.”

(Information regarding the Thiessen/Clark controversy is obtained from The Fundmentalist Harvard: Wheaton College and the Enduring Vitality of American Evangelicalism, 1919-1965 by Michael S. Hamilton and Clark: Personal Recollections by John W. Robbins.)

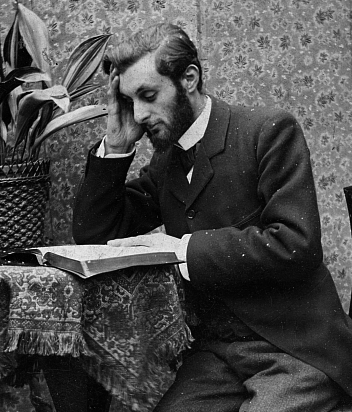

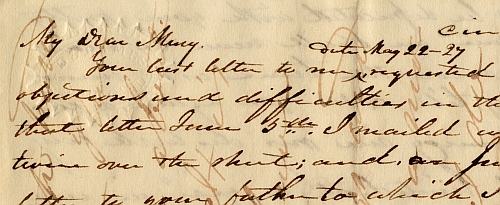

Throughout the summer of 1838 Jonathan Blanchard had thoughts of marriage on his mind, particularly, the thought of Mary Avery Bent who was residing in her natal Middlebury, Vermont after spending time as a teacher in Pennsylvania and Alabama. The correspondence between Jonathan and Mary, as well as between Jonathan and Mary’s father clearly gives one the sense of significance and weightiness of the prospect of their future together. In this time and place marriage was not entered into lightly and contrasts greatly with today’s expendable marriages.

Throughout the summer of 1838 Jonathan Blanchard had thoughts of marriage on his mind, particularly, the thought of Mary Avery Bent who was residing in her natal Middlebury, Vermont after spending time as a teacher in Pennsylvania and Alabama. The correspondence between Jonathan and Mary, as well as between Jonathan and Mary’s father clearly gives one the sense of significance and weightiness of the prospect of their future together. In this time and place marriage was not entered into lightly and contrasts greatly with today’s expendable marriages.