Vaughn Shoemaker, who died in 1991, was a Pulitzer Prize winning cartoonist for the Chicago Daily News and his work is as relevant today as it was when he sketched it. Along with being an acknowledged cartoonist, Shoemaker was a Christian whose work often displayed his convictions.

Vaughn Shoemaker, who died in 1991, was a Pulitzer Prize winning cartoonist for the Chicago Daily News and his work is as relevant today as it was when he sketched it. Along with being an acknowledged cartoonist, Shoemaker was a Christian whose work often displayed his convictions.

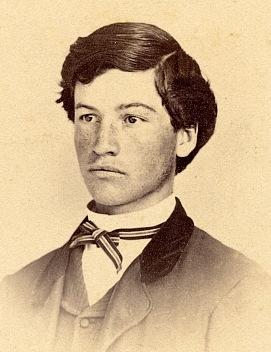

According to David Enlow in a tract titled Meet a Pulitzer Prize Winner, in 1918 Vaughn Shoemaker enrolled in the Chicago Academy of Fine Arts, with a class that was overcrowded and with many waiting to get in, the instructor, after three months, took to the task of weeding out the least likely to succeed. The first one picked was Shoemaker.

“You’ll never become a cartoonist in a thousand years,” said the director.

Twenty years later he had won his first Pulitzer Prize. Also he won the National Headliners Award, two National Safety top awards, eleven Freedom Foundation gold medals, topping it off with an honorary degree from Wheaton College and his second Pulitzer Prize.

What happened to transform this young man into a distinguished American cartoonist?

In 1917 as a lifeguard on a Chicago beach, he met a beautiful girl who later became Miss Chicago and it was love at first sight. Not only was this girl beautiful, but she was also sensible. It was “no go,” she said, unless Vaugn showed more signs of making some success in life.

With this incentive, Shoemaker found himself attracted by an ad in a magazine: “Draw this cartoon and become a famous cartoonist.” The fact that he had no particular aptitude in that direction did not stop him. Soon he found himself in art school, from whence came the director’s discouraging word.

An apprenticeship in the art department of the Chicago Daily News opened up, and this laid the groundwork for his 44 years of successful cartooning.

At the age of 20, a storybook situation brought the first break of his life. The chief cartoonist for the News left to take a position in New York City. His assistant had gone to take another position in the same city, and the second assistant had to leave because of illness in his family.

“You, Shoemaker!” the boss shouted. “Draw something, anything, until I can get a cartoonist somewhere.”

As he faced his dilemma, Vaughn thought of his mother, who years earlier had taught him to pray at her knee. Right in the chief cartoonist’s studio, he fell to his knees and asked God for help. Somehow, the cartoon came off his pen. He was known at The Chicago Daily News as a “gospel cartoonist.” He once said he started each cartoon “on my knees with a prayer.” He noted that the boys at the newspaper noticed it. Some laughed. “Some kidded me,” Shoemaker said. “I laughed back. There I stood: God helping me, I could do no other.”

In addition to his professional success, Shoemaker travelled far and wide to share the Good News of the Gospel which transformed his life.

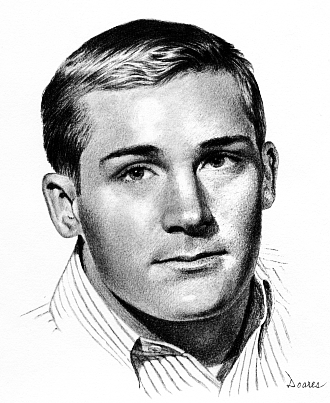

Shoemaker created the character John Q. Public and won two Pulitzer Prizes. Shoemaker’s most familiar character represented the beleaguered American taxpayer. The character appeared first in The Chicago Daily News, the paper on which Mr. Shoemaker began his career in 1922. In 1963 Mr. Shoemaker’s cartoons were syndicated to more than 75 newspapers. He worked at the Daily News for 27 years and then moved to the New York Herald Tribune, the Chicago American and the American’s successor, Chicago Today, where he retired. By the time he retired, in 1972, he had drawn 14,000 cartoons

Shoemaker created the character John Q. Public and won two Pulitzer Prizes. Shoemaker’s most familiar character represented the beleaguered American taxpayer. The character appeared first in The Chicago Daily News, the paper on which Mr. Shoemaker began his career in 1922. In 1963 Mr. Shoemaker’s cartoons were syndicated to more than 75 newspapers. He worked at the Daily News for 27 years and then moved to the New York Herald Tribune, the Chicago American and the American’s successor, Chicago Today, where he retired. By the time he retired, in 1972, he had drawn 14,000 cartoons

He won his first Pulitzer in 1938 for a drawing, “The Road Back,” which showed a World War I soldier marching backwards into war. The caption said, “You’re going the wrong way.” His cartoons were criticised by Herman Goering who described his work as “horrible examples of anti-Nazi propaganda.” In 1947, he won his second Pulitzer, for a cartoon titled, “Still Racing His Shadow.” In this cartoon a worker, marked “new wage demands,” tried to outrun his shadow, “cost of living.”

He won his first Pulitzer in 1938 for a drawing, “The Road Back,” which showed a World War I soldier marching backwards into war. The caption said, “You’re going the wrong way.” His cartoons were criticised by Herman Goering who described his work as “horrible examples of anti-Nazi propaganda.” In 1947, he won his second Pulitzer, for a cartoon titled, “Still Racing His Shadow.” In this cartoon a worker, marked “new wage demands,” tried to outrun his shadow, “cost of living.”

John L. Smith passed away Sunday, April 5, 2009 in Marlow, Oklahoma. Known to many as John L., Smith was born Monday, March 15, 1920 to Emmon and Viola Jeannetta (Gayle) Smith. In 1937 he graduated from Marlow High School and enrolled at Oklahoma Baptist University. He later attended Cameron University in Lawton, Oklahoma and Brigham Young University. He was awarded three honorary doctorates (Doctor of Divinity) and a Doctor of Theology from Southwestern Baptist Seminary.

John L. Smith passed away Sunday, April 5, 2009 in Marlow, Oklahoma. Known to many as John L., Smith was born Monday, March 15, 1920 to Emmon and Viola Jeannetta (Gayle) Smith. In 1937 he graduated from Marlow High School and enrolled at Oklahoma Baptist University. He later attended Cameron University in Lawton, Oklahoma and Brigham Young University. He was awarded three honorary doctorates (Doctor of Divinity) and a Doctor of Theology from Southwestern Baptist Seminary.

Sometimes that access can be thwarted by its own openness. While recently verifying the contents of a long-held collection of papers from a long-deceased faculty member (S. Richey Kamm) as the staff of the Archives & Special Collections finish development of our archival management system

Sometimes that access can be thwarted by its own openness. While recently verifying the contents of a long-held collection of papers from a long-deceased faculty member (S. Richey Kamm) as the staff of the Archives & Special Collections finish development of our archival management system