According to the Oxford English Dictionary, Hazing is “a species of brutal horseplay practiced on freshmen at some American Colleges.” For nearly thirty years from the Pre-WWII era until the 1960’s, Wheaton College was no exception to this tradition. The rivalry between the incoming freshman and sophomore classes arose from parties thrown in the 1920’s to actually honor the freshman by the sophomores. In 1933 the Student Council approved “organized torture for the incoming classes.” The sophomore class would elect people to the “sophomore courts” which had the authority to summon freshman who were not following the rules. Punishment for failing to obey the regulations was originally twenty swats with a bare hand. However, as time went on, these punishments became less severe. Any freshman who did not participate in the system lost their privilege to be involved with class activities.

According to the Oxford English Dictionary, Hazing is “a species of brutal horseplay practiced on freshmen at some American Colleges.” For nearly thirty years from the Pre-WWII era until the 1960’s, Wheaton College was no exception to this tradition. The rivalry between the incoming freshman and sophomore classes arose from parties thrown in the 1920’s to actually honor the freshman by the sophomores. In 1933 the Student Council approved “organized torture for the incoming classes.” The sophomore class would elect people to the “sophomore courts” which had the authority to summon freshman who were not following the rules. Punishment for failing to obey the regulations was originally twenty swats with a bare hand. However, as time went on, these punishments became less severe. Any freshman who did not participate in the system lost their privilege to be involved with class activities.

According to Freshman Hazing Rules listed in the Fall 1941 Record:

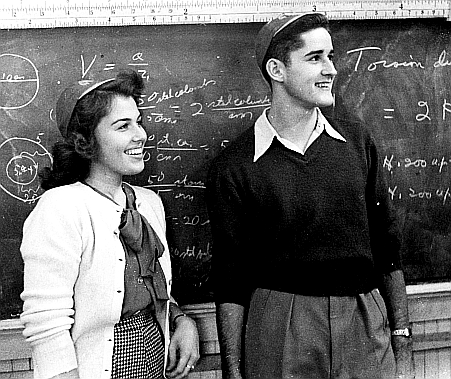

1. Dinks must be worn at all times except on Sunday and Friday evenings after 6:30 p.m.

2. Badges sold by the sophomore class must be worn at all times except Sunday and Friday evenings.

3. The following walks must not be used by freshman: between Williston and the Gym; between Williston and Blanchard; between Blanchard and the Gym; and the back entrance to the Stupe.

4. Keep off all grass on the entire campus.

5. At command “ATTENTION” given by a sophomore, the response is to simultaneously button with one hand and salute with the other and click the heels.

6. At command “BLITZKRIEG,” a white handkerchief knotted at each end, must be thrown in the air and caught on the head.

7. On Wednesdays, carry books in wastepaper basket. Boys will also carry whisk brooms and cloths to perform valet services for any upper classmen.

8. On Thursdays, both boys and girls must wear all clothes backwards, including dress shirts worn by boys. Walk backwards on campus. Girls’ hair must be in pigtails.

9. On Fridays, girls must wear one dress shoe with sock and one saddle shoe with stocking. Boys must wear clothes inside out, with one pant leg rolled to the knee.

10. On Saturdays, girls wear hair in curlers and war dresses and boys wear bow ties with crew neck shirts.