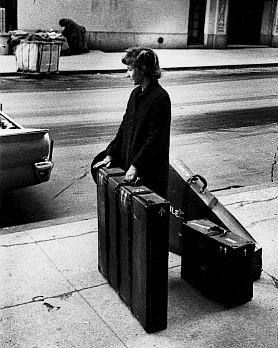

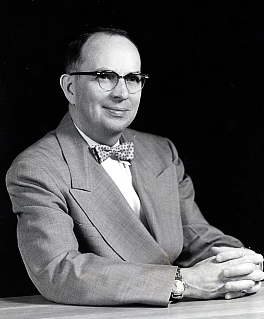

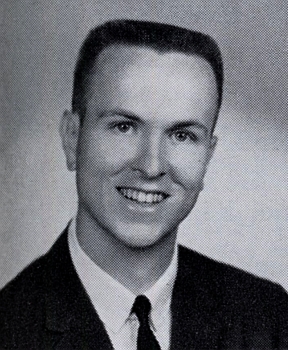

In 1960 a young man named Joslin “Josh” David McDowell transferred to Wheaton College from Kellogg, a community college in Michigan. His pastor had recommended the move. “Wheaton?” asked Josh. “Where’s that, Maryland?” Josh adjusted to Wheaton with some difficulty, his time fully occupied with studies or his house painting job. Advised by his pastor to gravitate toward the more pious students for fellowship, Josh did so, developing solid friendships with godly classmates, all eager to seek God’s face. One day as he waited at a crossing gate near campus, he noticed a car speeding up behind him. To his horror, the car – driven by a drunk – did not stop and barreled into him, pushing Josh’s vehicle onto the tracks at 45 mph. Fortunately Josh missed the path of the train. Though there was no visible injury, a sore neck indicated internal damage. Admitted to the college infirmary where he was confined to a cast and traction, he received a friendly visit from V. Raymond Edman, who stayed for two hours, praying with Josh. He later received a visit from Rev. Torrey Johnson, then-pastor of First Evangelical Free Church and founder (with Billy Graham) of Youth for Christ, who encouraged him in his desire to preach. After recovering, Josh and two friends met a visiting speaker named Bill Bright, founder of Campus Crusade for Christ. Joining the famous evangelist for coffee in the Stupe, Bright drew for them three circles with three thrones, each representing the kinds of people in the world, and who sits on their thrones: 1) the self-controlled unbeliever 2) the Christ-controlled Christian and 3) the carnal Christian. Josh then realized that he must endeavor to place Christ on the throne of his life. At that instant he entered a reinvigorated phase of evangelistic zeal, though he was still resistant to fully surrendering his life for service. Challenged by a “Spiritual Emphasis Week” message from Dr. Richard Halverson, Josh moved yet further toward yielding his will to Christ. That night, after late-night coffee at the Round the Clock cafe in downtown Wheaton, he walked Union Street in the cool, early hours of the morning, prayerfully struggling with the undeniable fact that God was beckoning, overwhelming Josh’s ambitions, calling him to a higher plane.

In 1960 a young man named Joslin “Josh” David McDowell transferred to Wheaton College from Kellogg, a community college in Michigan. His pastor had recommended the move. “Wheaton?” asked Josh. “Where’s that, Maryland?” Josh adjusted to Wheaton with some difficulty, his time fully occupied with studies or his house painting job. Advised by his pastor to gravitate toward the more pious students for fellowship, Josh did so, developing solid friendships with godly classmates, all eager to seek God’s face. One day as he waited at a crossing gate near campus, he noticed a car speeding up behind him. To his horror, the car – driven by a drunk – did not stop and barreled into him, pushing Josh’s vehicle onto the tracks at 45 mph. Fortunately Josh missed the path of the train. Though there was no visible injury, a sore neck indicated internal damage. Admitted to the college infirmary where he was confined to a cast and traction, he received a friendly visit from V. Raymond Edman, who stayed for two hours, praying with Josh. He later received a visit from Rev. Torrey Johnson, then-pastor of First Evangelical Free Church and founder (with Billy Graham) of Youth for Christ, who encouraged him in his desire to preach. After recovering, Josh and two friends met a visiting speaker named Bill Bright, founder of Campus Crusade for Christ. Joining the famous evangelist for coffee in the Stupe, Bright drew for them three circles with three thrones, each representing the kinds of people in the world, and who sits on their thrones: 1) the self-controlled unbeliever 2) the Christ-controlled Christian and 3) the carnal Christian. Josh then realized that he must endeavor to place Christ on the throne of his life. At that instant he entered a reinvigorated phase of evangelistic zeal, though he was still resistant to fully surrendering his life for service. Challenged by a “Spiritual Emphasis Week” message from Dr. Richard Halverson, Josh moved yet further toward yielding his will to Christ. That night, after late-night coffee at the Round the Clock cafe in downtown Wheaton, he walked Union Street in the cool, early hours of the morning, prayerfully struggling with the undeniable fact that God was beckoning, overwhelming Josh’s ambitions, calling him to a higher plane.  But it was not until he discovered Bright’s “Four Spiritual Laws” among his notebooks that he discerned a distinct purpose and direction for his ministry; and so he finally committed to the Spirit-filled life. This provided the basis for his public ministry, wherein he would engage unbelievers through apologetic debates and exhort weak or undecided believers to pursue the same dynamic empowerment that had revolutionized his own life.

But it was not until he discovered Bright’s “Four Spiritual Laws” among his notebooks that he discerned a distinct purpose and direction for his ministry; and so he finally committed to the Spirit-filled life. This provided the basis for his public ministry, wherein he would engage unbelievers through apologetic debates and exhort weak or undecided believers to pursue the same dynamic empowerment that had revolutionized his own life.

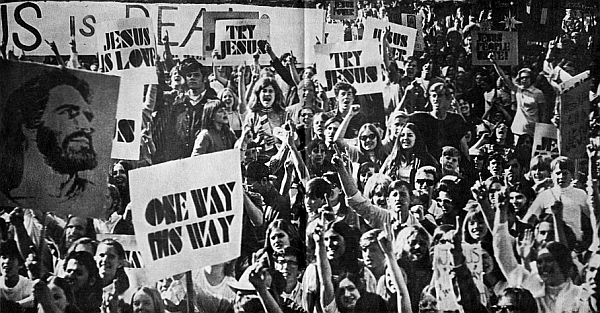

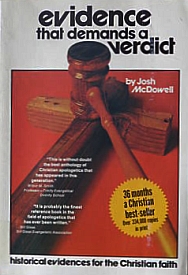

After Wheaton Josh attended Talbot Theological Seminary, graduating Magna Cum Laude with a Master of Divinity degree. In 1964 he joined the staff of Campus Crusade, preaching to thousands of students the world over; and in 1991 he founded Operation Carelift (now called Global Aid Network), one of the largest humanitarian aid organizations in the U.S. Among the 108 books he has authored or co-authored are Evidence that Demands a Verdict (1979), More than a Carpenter (1977) and The Last Christian Generation (2006). Still lecturing, he currently serves as president of Josh McDowell Ministries. His story, up to 1981, is told in Joe Musser’s Josh: The Excitement of the Unexpected.