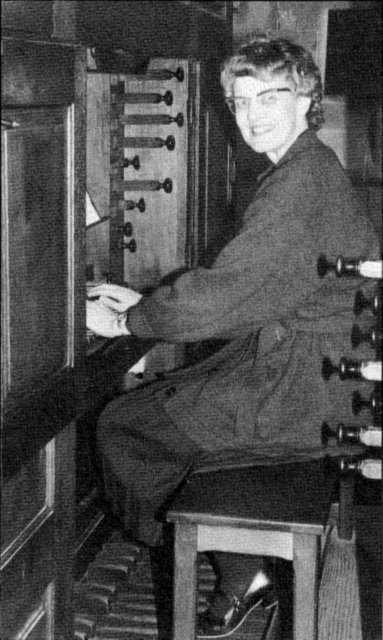

Twenty years ago, the Wheaton Alumni magazine began a series of articles in which Wheaton faculty told about their thinking, their research, or their favorite books and people. Professor Emerita of Communications Eleanor Paulson ’47 (who taught at Wheaton from 1952-1991) was featured in the Fall1992 issue.

Cicero described it as “the treasury and guardian of all things.” Shakespeare called it “The warder of the brain.” Charlotte Bronte wrote, “I prize her as my best friend.” The words of Mark Van Doren were, “It holds together past and present, gives continuity and dignity to human life. It is the companion, tutor, poet, library with which we travel.” These authors were referring to “Memory,” which serves to remind us of people, places and experiences we have encountered, and their significance in our lives.

Cicero described it as “the treasury and guardian of all things.” Shakespeare called it “The warder of the brain.” Charlotte Bronte wrote, “I prize her as my best friend.” The words of Mark Van Doren were, “It holds together past and present, gives continuity and dignity to human life. It is the companion, tutor, poet, library with which we travel.” These authors were referring to “Memory,” which serves to remind us of people, places and experiences we have encountered, and their significance in our lives.

Recently I attended my Wheaton College class reunion. We renewed friendships and shared memories of our college days: of first impressions of Wheaton, orientation and initiation by sophomores who required us to wear “dinks,” carry their hooks, and obey other commands. We remembered classes and special professors who challenged us with the excitement of learning. Beginning classes with devotions made a special impression on many of us.

In addition to classes and hours spent in the library there were trips to the Stupe, friendships to form, athletic events, dorm parties, Washington Banquets, and a Sneak” when we were seniors. We wore our Sunday best for dinner Friday evenings, and afterward attended Literary Society meetings. There were opportunities to be members of the many organizations on campus. Occasionally we took the “Aurora and Elgin” to Chicago, and Mrs. Smith, dean of women, reminded us that “Wheaton women wore hats and gloves.” A special time each day was the chapel service in Pierce. Dr. Edman, “Prexy,” spoke to us on such subjects as: “It’s Always Too Soon to Quit,” “Not Somehow, But Triumphantly,” “Don’t Doubt in the Dark What God Told You in the Light,” and the importance of living “For Christ and His Kingdom.”

Since graduation there have been additional memories added to my storehouse: teaching literature and speech to high school students in Almont, Michigan; teaching evening school at the Detroit Bible College; graduate work at Northwestern University, and then my return to Wheaton to teach. I shall never forget the beautiful spring day when I received a letter from Dr. Nystrom, chair of the speech department, inviting me to come to Wheaton to teach. That was a dream that came true!

For 39 years, I had the wonderful privilege of teaching Oral Interpretation of Literature, Speech for Teachers, Private Lessons, Public Speaking, and directing reading hours, recitals, and readers’ theater programs. I greatly enjoyed working with students in classes and programs, sharing their joys, their concerns, and their interests. They enriched my life in so many ways. In remembering the many students I had the privilege of knowing, I am reminded also of the many selections of literature we shared.

We experienced a sense of wonder as we read CS. Lewis’ “Creation of Narnia.”

We witnessed the transformation and joy of Scrooge as he discovered Christmas.

We shared the friendship between a little prince and a fox in the story by Saint-Exupery.

We shared in the adventures of Winnie-the-Pooh, Charlie Brown and his friends, the children in Narnia, Bilbo Baggins, and others.

We became immersed in discussions between the Karamazov brothers on the existence of God and immortality, Christ-like love, suffering, and forgiveness.

We accompanied Christian on his journey to the “Celestial City” in John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress.

We enjoyed the poetic expressions of Shakespeare, T.S. Eliot, Frost, Hopkins, e.e. cummings, Madeleine L’Engle, Luci Shaw, and many others.

We empathized with the experiences of a vast array of characters.

When we read of Sydney Carton’s death for his friend, Charles Darnay, in Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities, we were reminded of another death–for us–and of the words of Jesus, “I am the resurrection and the life. He that believes in me shall never die.”

We shared the oral reading of God’s Word, realizing the importance of reading it well, and the need for careful preparation to understand meanings and communicate effectively literary genres, guidelines for living, promises, the majesty of God, and his great love for us.

As I remembered shared literary experiences, I was reminded of Fairlight Spencer’s words in Catherine Marshall’s Christy, “It’s today I must be livin”; and of Psalm 118:24, “This is the day which the Lord has made. Let us rejoice and he glad in it.” Memories “hold past and present together,” but each new day is a gift to be lived to the fullest. With retirement, I have opened a new chapter in my life, with many new opportunities and joys to he experienced. There is a time for remembering, and there is a time to enjoy new experiences.

———-

For 39 years Professor Emerita Eleanor Paulson taught Oral Interpretation in Literature and other communications courses, and directed reading hours, recitals, and readers’ theater programs at Wheaton College. In 1985, she was honored as Alumna of the Year for “Distinguished Service to Alma Mater.” She retired last spring (1991) and is now occupied with many new activities travel, volunteer work, Bible study, church work, speaking engagements and other opportunities for service, enrichment, and spiritual growth.

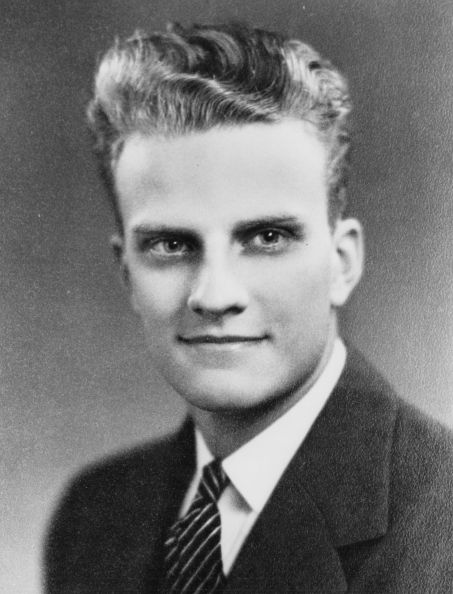

He was so absorbed in his subject that many times we would label him “the absent-minded professor.” These courses helped me in my world travels. I had no idea that the Lord was preparing me through these classes to learn to adapt to different tribal situations, different cultures, and different parts of the world that I was to preach to in the years to come.

He was so absorbed in his subject that many times we would label him “the absent-minded professor.” These courses helped me in my world travels. I had no idea that the Lord was preparing me through these classes to learn to adapt to different tribal situations, different cultures, and different parts of the world that I was to preach to in the years to come.